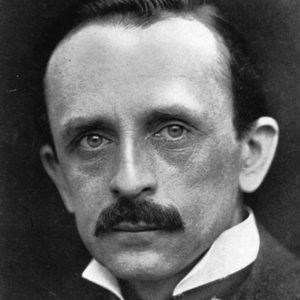

Kirriemuir playwright J M Barrie was decades ahead of his time in identifying key stages of child development, according to a new study.

Dr Rosalind Ridley said the Peter Pan author’s “accurate observation of animal and human behaviour precedes the analysis of these behaviours by the scientific community”.

She reveals that Barrie had an almost uncanny grasp of human cognitive development four to eight decades before psychologists began to work on similar questions about the way we develop thinking and reasoning skills.

In Peter Pan and the Mind of J M Barrie: An Exploration of Cognition and Consciousness, the neuroscientist “unpacks the magic and oddity of the tales that have captivated audiences for generations”.

Dr Ridley has a distinguished career in neuroscience research Cambridge University and the Medical Research Council.

Her work has focused on the brain mechanisms underlying cognitive processes such as learning, memory and problem solving.

Re-reading Barrie’s books for children she began to realise the extent to which the author had grasped many of the topics that she has spent her working life researching in order to come up with new treatments for dementia and to gain a better understanding of neurological conditions such as stroke which cause cognitive impairments.

Peter Pan and the Mind of J M Barrie is the first book of its kind to explore fully how Barrie delved into the complexity of the developing human mind in his writing.

Ridley argues that Barrie’s enduring appeal lies in his study of the unconscious mind – and its many quirks and foibles.

She writes: “It is Barrie’s deliberate use of cognitive mistakes and confusions in order to both amuse and illuminate the way we think that suggests that he was being intentionally analytical rather than descriptive.

“The weirdness of some of Barrie’s illogical stories suggests that he is tapping into something important in cognition.”

Ridley shows how Barrie created a narrative that works on several levels: as a coming-of-age story, as the myth of a golden age, as a fantasy to delight child and adult readers.

Most importantly, asserts Ridley, Barrie invented Peter Pan to “make some sense of his own emotional difficulties, to investigate the interplay between the world of facts and the world of imagination, and to re-discover the heightened experiences of infancy”.

Ridley, like most other scholars, sees Barrie’s tragic childhood as pivotal to his creativity.

His older brother died in a skating accident and remained more alive in their mother’s thoughts than her surviving son.

Barrie left Kirriemuir when he was 13 before going on to study at Edinburgh University, followed by a career in journalism.

He worked for 18 months as a staff journalist on the Nottingham Journal then returned to Angus, using his mother’s stories about Kirrie — which he renamed Thrums — for a piece submitted to the St James’s Gazette in London.

His “Scotch” pieces emerged at a time when the “kailyard” school of tartan writing was becoming a sensation.

A Window in Thrums was published in 1890 among a set of Thrums novels, before Barrie moved into play writing.

In 1902, the Admirable Crichton appeared, followed by Peter Pan in 1904.