As soft fruit growers fear another year of berries being left to rot due to a lack of pickers, Michael Alexander speaks to several Tayside farmers about the pressures being faced and the challenges ahead.

It is a UK industry said to be worth over £1.6 billion a year, the value of which has doubled in just a decade.

But Tayside and Fife soft fruit farmers are warning that labour shortages caused by Brexit, Covid-19 and now the Ukraine war could again see fruit left rotting on their plants.

Add to this rising costs plus higher than normal wage increases for seasonal visa scheme workers being imposed by the UK government, and industry representatives say an incredibly challenging season lies ahead.

Reliance on East European labour

Jill Witheyman is head of marketing at Angus Soft Fruits Ltd, based at East Seaton Farm, Arbroath.

As a leading supplier of berries to UK and European retailers, spring this year has been favourable to the soft fruit industry in Scotland.

The 12,000 tonnes of fruit grown annually by their growers is tasting “absolutely delicious”.

There’s a feeling, however, that everything seems to be working against the industry right now.

She says it’s been “an incredibly challenging few years” securing labour with Brexit, Covid-19 and now the Ukraine war.

However, to add to this challenging mix, the Home Office introduced a significant increase to labour costs through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Scheme (SAWS) scheme in April, meaning farms must now pay £10.10 per hour for seasonal migrant workers versus the £9.50 per hour National Living Wage for UK workers.

This change, which farmers say is a post-Brexit attempt to dissuade them from using foreign labour, was implemented six weeks before the British soft fruits season started without industry consultation.

Farmers say, however, the policy fails to understand the industry’s reliance on mainly East European labour and the relative unavailability of home workers.

“There are many challenges facing the industry with rising costs across all areas of the business,” she says.

“Increased costs of raw materials, increased transportation costs, increased energy costs, increased labour costs, increased fuel costs.

“However, the biggest challenge facing the industry is labour scarcity.

“It is predicted that fruit shall rot on the plants in Angus and Tayside, by mid-June due to labour shortages, where growers will have to walk away from crops.

“This will be an incredibly challenging season.”

Farmer’s view: East Scryne Fruit Farm

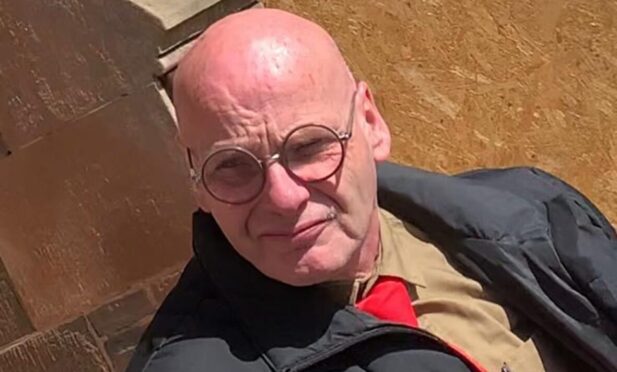

Amongst the farmers who’d like to see the extra SAWS payments and restrictions on the numbers of overseas workers permitted to work in the industry reduced, is James Porter of East Scryne Fruit Farm, near Carnoustie.

The 51-year-old’s family have been farming at the 350 acre mixed farm since 1942.

Since his father William started growing strawberries in the 1960s, the soft fruit part of the business has grown significantly.

Strawberries and blueberries have been sold to supermarkets like Sainsbury’s and M&S since the early 1990s.

Taking advantage of the relatively mild microclimate on the Angus coast, they produce around 1000 tonnes per annum across 100 acres, grown from the beginning of May until October and sold as part of Angus Soft Fruits.

Times have been “pretty tough”, however and with Angus Soft Fruits needing about 4000 seasonal workers across the board for the season, James says it’s getting “harder and harder to get a decent squad of people to pick berries”.

“During Covid a lot came that were on furlough and that was a great help,” he says.

“But when their old jobs came back and everyone got back to work, the numbers fell away again.

“We need a seasonal workers scheme but unfortunately the government has decided they are going to make us pay £10.10 an hour to use that scheme, and for the amount we get paid for the fruit it just doesn’t add up anymore.”

James explains that before Brexit, most of their seasonal workers came from Eastern Europe.

Now, recruited mainly through the Concordia agency, that’s still the case.

They get a lot of returnees, including many residing in the UK who now have settled status.

However, the UK government is “doing its best to stop using the migration route”, he says, and many are being sourced from further afield.

Why can’t ‘local’ berry pickers be used?

Some people have suggested the answer to the labour shortage is the recruitment of ‘local’ workers.

Many well-up with misty-eyed nostalgia about the days of the ‘berry buses’ when Fife and Tayside residents would flock to the berry fields each summer.

But while local people are welcome, James says there are several reasons why it’s unrealistic to rely on this as a main workforce.

The main issue deterring locally-sourced labour, he says, is that it’s a hard, seasonal, physical job now spread out over a much longer season and on a much bigger scale.

With “not a huge amount of unemployment in Angus”, and now with the war in Ukraine limiting routes from where other workers were expected to come, posts are increasingly difficult to fill.

“We’ve had all sorts of Eastern European nationalities on the farm – a real mixture, and they all seem to get on reasonably well,” he says.

“We have workers from Bulgaria, Romania, Poland. I think we’ve got some from as far away as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. I know there are some workers on farms in Angus from Nepal.

“But we have got Ukrainians on the farm as well.

“There were some Ukrainians already here and some who’ve managed to get out to come here.

“There are actually some Russians as well on the farm. They arrived before the war started and they just seem to be getting on with the Ukrainians. They are not looking for any trouble.

“I saw a Russian lad walking up the road carrying the shopping for this Ukrainian lady the other day.

“But I would say across the piece the whole industry is concerned about labour shortages.”

Farmer’s view: Stewarts of Tayside Ltd

Down the coast at Tofthill, nestled on the banks of the River Tay at Glencarse near Perth, family-run independent direct grower Stewarts of Tayside Ltd pride themselves on their quality of produce and the efficiency of growing, harvesting, packing and delivering to customers.

With an annual turnover of over £30 million, and their main crops comprising 260 acres of strawberries, raspberries and 2500 acres of swede, they also run a transport fleet of 34 lorries.

This chimes with their motto that they like to be in total control of everything they do.

The bulk of their soft fruits end up in supermarkets across the UK.

According to managing director Liam Stewart, however, the realities of Brexit, which he was “absolutely against”, mean they are no longer in control of their labour.

With 200 full-time staff, their ability to fill all of their 700+ additional seasonal fruit picking posts has been hampered.

“It’s always been a challenging industry because there are natural factors that effect farming such as the weather which you can’t control,” he says.

“But the problems really started three or four years ago with Brexit, which has really impacted our labour situation.”

Liam said that decades ago, labour was mainly sourced locally.

At risk of generalising, however, as living standards have increased and societal expectations have risen, local people have become increasingly unwilling to take on hard intensive roles.

To compensate, farmers had to increasingly source labour from overseas, reaching a point years ago, long before Brexit, where they became heavily reliant on Eastern Europe.

To compete in today’s pressurised fruit and veg markets, operations have to be highly efficient over a much longer growing season.

Impact of Brexit

When Brexit came into play, however, businesses have gone from being able to recruit their own labour reasonably successfully to now having to go through agencies who are allocated restricted permits.

Not only does this move Stewarts away from their business model of keeping everything in-house, they are competing for the same labour with agencies supplying the whole of the UK produce industry.

Being short of labour puts extra pressure on the workforce, it drives prices up because people are working more overtime, and people get more tired working longer hours.

Brexit, meanwhile, has also “crushed” Stewarts’ swede export business. While they still have access to their main markets in Germany and France, paperwork, inspections and red tape has made it “very complicated”.

The pandemic also brought challenges. While they were able to get labour, they had to isolate all the labour before they could go out to work.

Stewarts still employs many East Europeans and, at the time of this interview, is advertising for jobs in Polish, Bulgarian and Romanian, as well as English.

What’s changed, however, is the workforce make-up. For example, as Poland’s economy has grown there’s been less appetite for Polish people to come to Britain.

Those still employed tend to be those who’ve “climbed the ladder” into supervisory roles and have settled status.

By contrast, those coming via agencies are now more likely to be from Bulgaria, Romania or even further afield such as Kazakhstan or Tajikistan.

The business has become heavily reliant on Ukrainian workers for the last couple of years.

Praise for hard working East Europeans

Liam is full of praise for the mainly young Ukrainian women in their 20s who work “incredibly hard with a smile on their faces” – despite being “worried sick” about their husbands and boyfriends fighting back home, or their family homes having been “blown to smithereens”.

He describes the East Europeans as having a “totally different mind-set” and they “just get on with it”.

However, since the war’s broken out, it’s inevitably had another massive impact on the industry and numbers are down.

“It’s a real mix of labour, and that’s not a good thing for us because it makes it difficult to manage,” he says.

“If they don’t speak English or are less well educated, if you’ve got multiple different nationalities, that means you need multiple different supervisors for each nationality.

“The training becomes more difficult and more time consuming. It’s not a great situation.

“In an ideal world as a grower we’d like all our labour to come from Scotland locally.

“We wouldn’t have to put on transport, accommodate, they’d all speak English, they’d all be educated. Everyone is a winner! But it’s just not like that!”

‘Lack of understanding’ by UK government

Liam says the “biggest frustration” for them as a produce business is the “lack of understanding by the British government in terms of labour”.

He adds: “We need the government to appreciate and understand there are problems with labour.

“If it was as simple as ‘let’s stop bringing in all these East Europeans and be self sufficient’ – great!

“But unfortunately it isn’t like that.”

There are similar concerns In Fife. NFU Scotland horticultural spokesperson Iain Brown of Easter Grangemuir Farm at Pittenweem, recently said he was without a quarter of the pickers he needs to harvest his crop of strawberries.

Migrant workers have also complained that paying £259 for a UK visa is too high, putting many off.

Rebuttal by the Home Office

The Home Office has given a firm rebuttal to claims it has acted illegally by introducing a higher minimum wage for seasonal workers than for British nationals working in the UK horticulture sector on the national living wage.

With 55,000 workers needed to pick fruit and veg across the UK, the UK government has said it fully acknowledges the food and farming industry is facing labour challenges and is continuing to work with the sector to mitigate them.

It says it has given the industry greater certainty in accessing seasonal, migrant labour by extending the seasonal workers visa route until the end of 2024.

This allows overseas workers to come to the UK for up to six months to work in the horticulture sector, in addition to EU nationals living in the UK with settled or pre-settled status.

On Monday, Defra announced 10,000 more seasonal agriculture visas as part of the UK Government’s Food Strategy.

North-east Tory MP Andrew Bowie welcomed this as a step in the right direction.

However, he acknowledged more needs to be done to promote Scottish and British soft fruit farmers and farming more widely, not just because of the high quality produce that they provide but because of concern about air miles and national food security.

Conversation