A Montrose-born sailor died on HMS Bounty under the command of Lieutenant William Bligh, before many of the crew mutinied in 1789.

In an incredible twist of fate, the link between the coastal town and one of the most infamous episodes in naval history was uncovered by the crew of HMS Montrose, as they headed toward Pitcairn Island where many of the mutineers settled.

It is hoped living descendants can be traced.

Able-bodied seaman James Valentine died on board the ill-fated vessel in 1788.

At twenty-eight years old, Valentine was one of the youngest and healthiest seamen on board the ship.

However, when the Bounty docked at Adventure Bay, he felt “somewhat indisposed”, and made what would ultimately be the fatal mistake of consulting the ship’s physician Dr Huggan.

Huggan, a chronic alcoholic also destined to die on the voyage, decided to bleed Valentine – a common treatment at the time – and the wound became infected.

In a prescient example of how poor communication was on the small vessel, Bligh was not told about how serious the man’s condition was until the patient was dying.

In a cruel twist, it is believed the sailor may have actually been suffering from a bout of asthma.

The Montrose man’s condition deteriorated daily as the infection spread, and he died on October 9, just weeks before the ship docked at Tahiti. He was buried at sea.

He was the first of the Bounty’s crew to die.

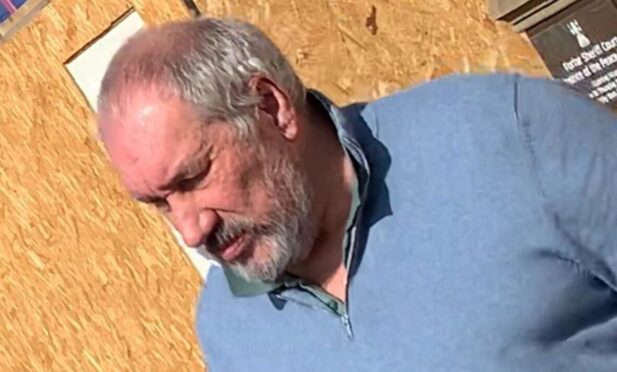

Montrose and District Conservative councillor Ron Sturrock, himself a former sea Captain said: “This is an absolutely fascinating discovery, and I hope that some of James Valentine’s family might still live in the area.

“I’d like to commend the crew of HMS Montrose for highlighting the town’s link to this famous event, and wish them a safe voyage until we next see them dock in Montrose.”

The Mutiny on the Bounty

The Bounty, a three masted vessel just 91 feet long and 25 feet across at her widest point, and a crew of 46, was an unlikely candidate to play the central role in one of the most infamous events in British maritime history.

The ship had left the UK in 1787 to collect and transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the West Indies, where the intention was to cultivate it as a food source.

Despite having hand-picked many of his crew, Lieutenant Bligh, who had been highly recommended to command the mission, became increasingly belligerent toward his officers and crew.

During the extended layover in Tahiti, discipline became lax and Bligh began dispensing increasingly harsh punishments, abuse and criticism, including berating his officers in front of the crew.

After three weeks back at sea, the Master’s Mate Fletcher Christian led the now famous mutiny which has been immortalised many times in print and on film.

Bligh and some of his supporters were forced from the ship into a small open boat, and in an incredible feat of navigation, sailed some 6,500 km to reach safety, where he alerted the authorities to the mutiny.

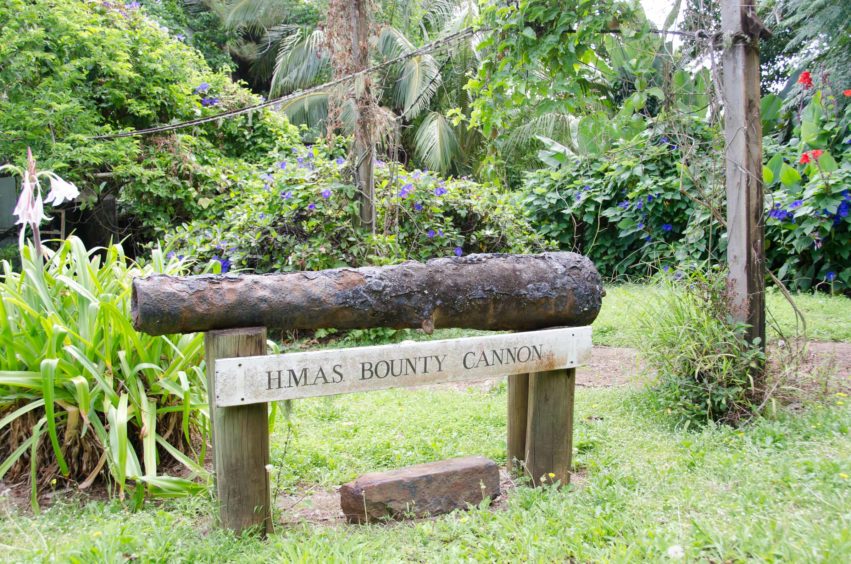

Christian meanwhile, sailed the Bounty to Tubuai island in an unsuccessful bid to settle there, then to Tahiti, but finally settled in Pitcairn Island, where descendants of the crew still live.

Bligh was initially lauded on his return, and honourably acquitted at the court-martial but public opinion would later turn against him.

A variety of fates awaited those of his crew who returned to the UK, including acquittal and royal pardon, although some were hanged.

Bligh was promoted to vice-admiral in 1814, but was dogged by controversy and did not receive the offer of further naval appointments. He died in 1817.

The Dundee connection with Bligh

Serving with Valentine was not the last time Bligh would find himself with a Tayside connection.

In 1797 he served under Dundee born Admiral Adam Duncan during the decisive battle of Camperdown when Duncan led the British fleet to victory against the Dutch, who were aligned with the Revolutionary French.

The battle, which ironically was fought against a backdrop of other British naval mutinies, saw Duncan lead fourteen ships of the line, four frigates and six sloops against an almost equally matched Dutch force.

Captain Bligh commanded HMS Veteran, a 64 gun, third rate ship of the line, which had been launched a decade earlier.

HMS Veteran suffered some damage to her masts and rigging, with seven crew wounded, although none were killed.

The battle was a complete success for the British, but resulted in significant casualties, with the British losing 203 killed and 622 wounded, while the Dutch force saw 540 killed, 620 wounded and eleven ships captured by Duncan’s forces.

For his inspiring leadership, Admiral Duncan was raised to the peerage as Viscount Duncan of Camperdown and Baron Duncan of Lundie, and was awarded the Large Naval Gold Medal and an annual pension of £3,000.

Following the battle, Duncan received a heroes welcome around the country, lavished with gifts and immortalised in art.

Bligh too secured a place in history, but for entirely different reasons.