Michael Alexander goes underground on a tour of a former ‘secret’ nuclear monitoring post in Arbroath.

At the end of a small private road leading off the A92 just beyond the Elliot Caravan Park in Arbroath, an unremarkable farm track turns up the hill towards a small gated compound containing some cabins.

In the centre, the only indication that something unusual can be found here is an area of grass and slabs with a large metal box, some protruding vents and a ‘Danger keep out’ sign.

But these first impressions belie the former Royal Observer Corps (ROC) nuclear monitoring post buried 15 feet underground.

Until 28 years ago, this underground relic of the Cold War would have been on the front line in the event of a nuclear attack on the UK, providing a place for three ROC volunteers to measure nuclear blast waves and radioactive fallout.

Between 1956 and 1965, the UK government ordered the construction of 1,563 such posts at a distance of about 10 miles apart including the likes of Cupar, St Andrews and Arbroath.

Thirty-one larger HQ and control centres – like the 28 Group HQ at Craigiebarns in Dundee – were also built.

As the Cold War came to an end with the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the sites were all closed down when the ROC was stood down in 1991.

Many of the sites were subsequently demolished or fell into disrepair.

But some have been preserved by private individuals or trusts, and today, the Arbroath ROC 38 Post is one of only two refurbished posts open for access in Scotland and includes a collection of its original equipment and instrumentation.

A surface museum has also been established displaying memorabilia relating to the former ROC.

In addition there is a collection of material from the ROC’s original role of aircraft identification and reporting from 1925 to 1945 – originally at the Arbroath water tower – and the remains of the reporting post.

The Courier was invited to join former ROC member Cheryl Stewart, 68 – the owner and restorer of the Arbroath site – on a tour of the underground complex, which was designed to house three volunteers for two or three weeks but which in reality, it is now thought, may not have been able to protect them for long against the realities of a nuclear attack.

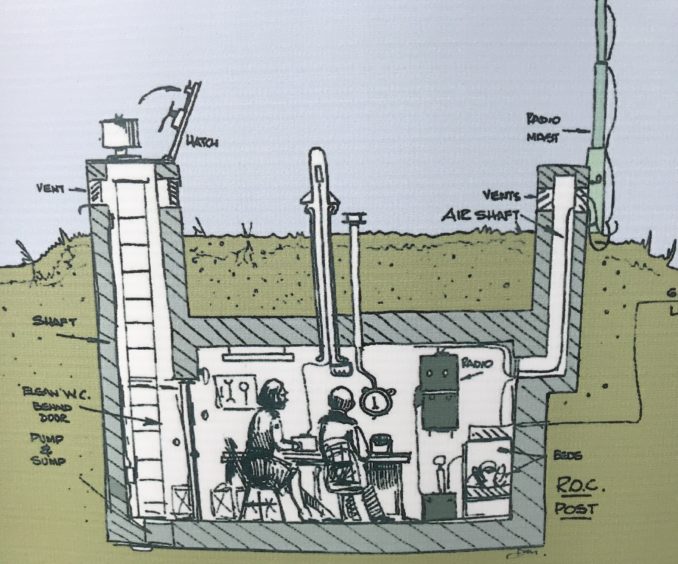

Opening a surprisingly thin blast proof hatch and clambering down the 15 feet long ladder housed inside a tight vertical access shaft, we step onto a grill where ROC volunteers would have been crudely washed down with a hose to remove any radioactivity before entering the claustrophic single-roomed bunker housing communications, bunk beds, a table crowded with monitoring equipment and maps showing the network of former bunkers in Scotland.

Protected by 10-inch thick concrete walls which were bitumined then protected with a layer of bricks and three feet of soil above, the bunker has an ambient temperature of eight degrees.

However, it was not fitted with an air filtration system, fresh water supply or electric lights and just a thin wooden door separated the ladder shaft and toilet from the main living area.

“There were a number of military establishments in this area so it’s quite likely that a nuclear weapon would have been dropped somewhere around in the event of a nuclear war,” said Cheryl, who was in the Inverness-shire group ROC from 1976 to 1984 and restored it after buying the then dilapidated complex in 2003.

“If one had been dropped right on top of us we could have said ‘goodbye’.

“But if there had been one over in Fife, depending on the size of the weapon – how long is a piece of string?”

Cheryl explained that volunteers trained in peacetime with 10 members. In an emergency a rota system would have been drawn up with three members underground at any one time.

“Whoever the lucky three were when the ‘balloon’ went up would have been underground for two/three weeks,” she explained.

“We had rations for that period of time.”

Equipment included a bomb power indicator which would have measured the over-pressure of the blast wave.

Information would be fed back to control centres to inform the authorities as to when it might be safe – if ever – to evacuate any surviving civilians.

“We had standard operating procedures,” said Cheryl.

“We were a disciplined group of people who knew how to report into our HQ and use our instruments and take our information off the instruments that would have been so vital in warning the public of radiation.

“But the reality is everyone would have been very frightened and the observers would have been very cold. It’s also very possible that observers themselves wouldn’t have survived long.

“The wooden door wouldn’t have given much protection. They would have been ingesting contaminated air.

“Why they left us wide open to radiation coming through that hatch I don’t know.”

Cheryl, who removes everything of value from the bunker when not open to the public, says the majority of people she speaks to in Arbroath still seem unaware that the post existed.

“I think it’s important to restore it and tell people about it – especially youngsters who often don’t have an inkling to what went on in the Cold War years,” she said.

“It’s an important part of history. From 1947 to 1991.

“It’s also of interest to older people. So few people knew that an organisation existed or that a place even existed that would help them.

“The idea was to get information to the authorities that once they knew where the radiation was travelling they’d be able to warn the public to hunker down and if the public had done what the government had advised – to build inner refuge in house until radiation had moved on with the wind – then the authorities would have gone in and evacuated.

“I often say, however, you might have been better to let a bit of radiation in instead of oxygen (just to finish things off)!”