When Alex Salmond was cleared of sexually assaulting nine women at the High Court in Edinburgh it was far from the end of the story.

The former first minister signalled as much with his thinly veiled warning outside the court after he was found not guilty of 12 sexual assault charges, including one of attempted rape, and not proven when it came to one of sexual assault with intent to rape.

Mr Salmond promised a sequel to one of the most dramatic episodes in Scottish politics when he said there was “certain evidence” that was not heard in court but he wanted “to see the light” of day eventually.

That sequel will gradually unfold over the coming weeks and months as no fewer than three official inquiries that have been launched into the Salmond saga get under way.

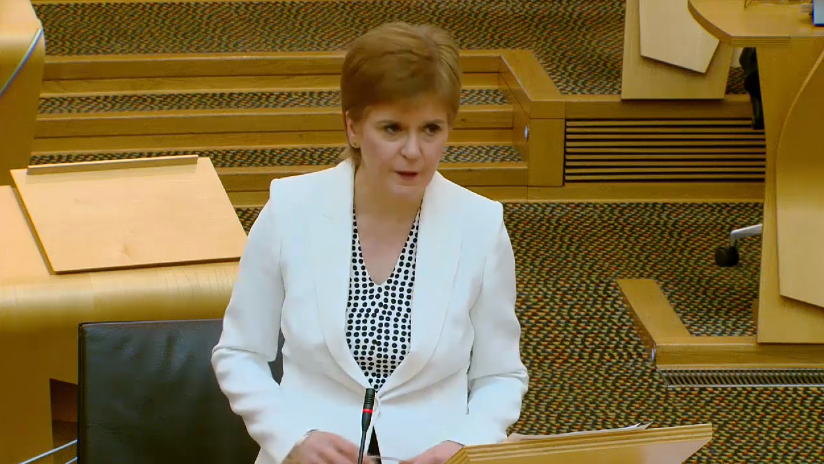

Under the microscope will be how the Scottish Government handled sexual harassment complaints made against Mr Salmond. Also scrutinised will be the role played by a host of prominent Scottish figures including First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and Permanent Secretary Leslie Evans.

Here is a breakdown of the three inquiries and the issues they will examine.

The Holyrood inquiry

This has the potential to be the most thorough and interesting of all the investigations when it resumes this week. It also promises compelling political theatre with Mr Salmond, Ms Sturgeon, her husband and SNP chief executive Peter Murrell and Ms Evans expected to give evidence.

From Mr Salmond’s point of view, it should give him the chance to raise some of the “evidence” that was not heard when he faced criminal charges at the High Court. Mr Salmond’s supporters have claimed the former SNP leader has been the victim of a conspiracy.

During his trial, Mr Salmond said some of the charges against him were “fabrications for a political purpose”. Ms Sturgeon, on the other hand, has dismissed claims that her allies in the party conspired against Mr Salmond as a “heap of nonsense”.

The tensions between the Salmond and Sturgeon wings of the party will be a dominant theme of the inquiry when MSPs start taking oral evidence in September.

The Holyrood Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints” was established in the aftermath of Mr Salmond’s successful civil action against the Scottish Government at the beginning of last year.

Chaired by the SNP MSP Linda Fabiani, it will examine the circumstances that led to the Scottish Government’s case collapsing, which resulted in the taxpayer shelling out more than £500,000 for Mr Salmond’s legal costs.

MSPs on the committee will scrutinise how the Scottish Government acted when two sexual harassment complaints were made against Mr Salmond in January 2018. The complaints were dealt with under a new complaints procedure drawn up by Ms Evans and signed off by Ms Sturgeon in 2017.

Mr Salmond was adamant the process was unfair and launched a judicial review against the government he once led. The Scottish Government had intended to fight Mr Salmond in the courts, but before the case went to a full hearing it admitted it had acted unlawfully. Lord Pentland described the government’s investigation as “tainted with apparent bias”.

The government had breached its own procedures by appointing an official, Judith MacKinnon, to conduct an investigation that was supposed to be independent, even though she had already met both complainants. After his civil court victory, Mr Salmond called on Ms Evans to resign, arguing she bore ultimate responsibility for the botched investigation as Scotland’s most senior civil servant.

The actions taken by Ms Evans and Ms MacKinnon, who is also expected to give evidence, will be part of the Holyrood inquiry, as will questions about why the Scottish Government’s new complaints procedure was applied retrospectively to former ministers.

After a long delay caused by the coronavirus crisis and Mr Salmond’s criminal case, the committee will meet this week to deal with administrative details. Members will call for the public evidence sessions to be attended by witnesses in person in the Holyrood chamber, despite the coronavirus restrictions. MSPs on the committee believe that virtual sessions would prevent the forensic cross-examination of witnesses.

There will also be discussions about what written evidence is required before witnesses give oral evidence over six to eight weeks from September.

A focal point is likely to be when Ms Sturgeon is called to give evidence about discussions she had with Mr Salmond about the complaints made against him.

Ms Sturgeon had conversations with her predecessor on five occasions after the original complaints had been made.

These conversations included two meetings in Ms Sturgeon’s house in Glasgow. Ms Sturgeon has told reporters that her husband, Mr Murrell, was aware of the meetings with Mr Salmond in the family home, but was unaware of the subject matter.

These meetings and phone calls are also the subject of a second inquiry into whether they amount to a breach of the ministerial code by Ms Sturgeon.

The Ministerial Code inquiry

When Ms Sturgeon disclosed to parliament her five conversations with Mr Salmond her opponents were quick to suggest that she had breached the ministerial code, the code of conduct for senior politicians in government.

The code states meetings on official government business have to be set up through the government office and that detailed records need to be made of those contacts.

It adds: “If ministers meet external organisations or individuals and find themselves discussing official business without an official present – for example, at a party conference, social occasion or on holiday – any significant content (such as substantive issues relating to government decisions or contracts) should be passed back to their private offices as soon as possible after the event.”

In January last year Ms Sturgeon told Holyrood that she did not inform civil servants of her April 2 meeting with the former first minister until two months after the event.

She also revealed Mr Salmond also called Ms Sturgeon on April 23 and a second meeting was arranged in Aberdeen in June before the SNP conference in the Granite City.

On June 6 Ms Sturgeon finally wrote to Ms Evans to tell her about her meeting and that she knew about the investigation into Mr Salmond. The following day she kept her appointment in Aberdeen with Mr Salmond.

On July 14 the pair met again in Ms Sturgeon’s Glasgow home. Another phone call between the two politicians was made on July 18.

After pressure from opposition Ms Sturgeon referred herself to the advisers who regulate the ministerial code, despite her insistence that she had acted within the rules.

Since then it emerged during Mr Salmond’s trial that his former chief of staff, Geoff Aberdein, met Ms Sturgeon in her Scottish Parliament office in March 2018, days before the first confirmed meeting.

Mr Aberdein’s meeting is likely to come up at the Holyrood inquiry as well as this one, which is overseen by the independent advisers charged with overseeing the Ministerial Code. The advisers are the former Lord Advocate Dame Elish Angiolini QC and James Hamilton, the former Irish Director of Public Prosecutions.

The scope of their investigation is much narrower than the parliamentary one and it will be conducted in private. Mr Salmond himself was no stranger to such inquiries. He was referred to the advisers on six occasions, but was never found to have breached the code.

The Government’s internal inquiry

This will be conducted in private and is an internal investigation, but has been held up by the Covid crisis. A Scottish Government spokesman said Ms Evans had made clear this should take place “as soon as the time and resources being devoted to responding to the current health emergency allow”.

The spokesman added: “Subject to those ongoing pressures, the review is being taken forward.”