Scotland’s not proven verdict has become a live election issue after political parties signalled their intent to remove it. The Courier gathered expert opinion to examine whether Scots Law is ready for a fundamental shake-up.

The debate

“That bastard verdict.”

The summation of Sir Walter Scott of Scotland’s “third” verdict was coined before the modern vernacular but seems all the more relevant now.

Not proven has plagued legal experts and commentators for generations.

It is fairly clear in its origins – the Crown is charged with proving a case and if it does not do so, the jury has the option to say so and the accused leaves the dock without a conviction.

Not proven does not indicate an accused’s acquittal, despite doubts over the evidence – it is a clear indication of innocence.

Its presence does not provide a “get out” for uncertain juries – the accused walks from the court without a stain on their character in the eyes of the law, regardless of the acquittal verdict.

Such has been the case for as many as one in five jury acquittals in recent years including in 2019, the alleged killer of Annalise Johnstone in Perthshire, Fife “sexsomniac” Darrell Swanson and Robert Chambers, who ended promising footballer John Black’s career with a single punch in Dundee in 2018.

Its effect in law is no different to the linguistically-clearer not guilty, yet leaves an undesirable ambiguity at the conclusion of proceedings.

And therein lies the major flaw. An archaic three-verdict system, while legally clear, muddies the waters of public – and sometimes professional opinion.

If an accused is not guilty, they deserve to be labelled as such.

Studies have shown the third verdict does not materially affect conviction rates, except where the evidence against the accused is only moderately strong, hence the particular issue in sexual assault and rape cases, which are far less likely to feature strong corroboration.

While some may say it is actually the guilty/ not guilty verdicts which must be scrapped, leaving juries merely to determine whether the Crown has carried out its trial function, we are too far down the road for inviting such further confusion.

An unexpected entry into the Scottish parliamentary election campaign, the Scottish Conservatives have backed its axing and Nicola Sturgeon said at the weekend she would back a review.

The campaigner

Rape survivor Miss M has lobbied for change since her attacker was acquitted with a not proven verdict.

She was raped at St Andrews University in 2013 but took she took her case to the civil court and was awarded £80,000 after the criminal trial.

People don’t understand what not proven is”

– Campaigner Miss M

“Scotland is the only European nation to have a third verdict in criminal cases, not proven.

“The certainty we apply to guilty and not guilty does not apply to not proven.

“People don’t understand what not proven is. There’s no definition to what it means.”

She welcomed recent political discourse.

“It’s great to see the conversation had at this level. Hopefully they follow through.”

The charity

Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre Perth and Kinross (RASAC PK) manager Jen Stewart believes justice is jeopardised when those found not guilty and not proven face the same outcome.

She said: “RASAC PK fully support the continuing conversation around abolishing the not proven verdict.

“The not proven verdict is disproportionately used in rape and sexual assault trials, resulting in conviction rates which are consistently lower than any other crime.

“There is evidence that preconceived ideas about how someone should react following a rape influences juries and can make them less likely to deliver a guilty verdict.

“Not proven convictions have the same outcome for the accused as not guilty, they are both acquittals.

“This too often results in perpetrators walking free from court and the impact of a not proven can be as distressing for survivors as a not guilty.

“We believe that in order to improve the justice process for survivors, significant change is needed and we would fully support the abolition of not proven as part of this change.”

The Advocates

Ronnie Renucci QC, Vice-Dean at Faculty of Advocates, said wider reform is needed than merely scrapping one verdict.

“To those working with juries day in day out it is difficult to understand how the not proven verdict has now become the scapegoat for decisions, that although unpopular with some, have been carefully considered by a jury who have had the benefit of hearing all of the evidence.

“It should not be forgotten that in cases involving allegations of sexual offences, juries are the only members of the public who hear all of the evidence as the complainer’s evidence is heard in private.

“It is easy to jump on a bandwagon and cry for the outlawing of something we or others don’t like without identifying the necessary changes that require to be made to our jury system, changes that would be necessary in order to counter balance such a radical move and preserve the balance of fairness fundamental to any democratic jury system.

“Until such appropriate and proportionate changes are identified the Faculty opposes the removal of the not proven verdict.

“It is somewhat ironic that at a time when Scotland has led the way with its solution to conducting jury trials at an unprecedented rate throughout the pandemic by the innovation of remote jury centres, so many seem united in yet another step towards the anglicisation of our wholly unique and envied legal system.”

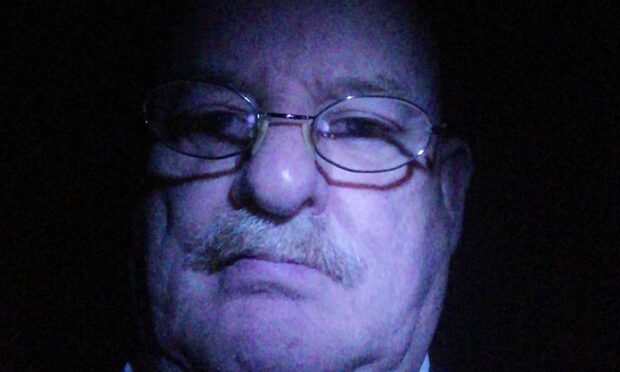

Donald Findlay QC has urged both First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and Scottish Conservatives leader Douglas Ross to rethink their stances on the issue.

Former St Andrews University rector Mr Findlay QC backs not proven, which he insists covers a wider spectrum of accused individuals than guilty people who were saved from conviction by a lack of evidence.

Two decades ago, Mr Findlay QC published a book, “Bastard Verdict”, examining the contentious outcome and defending the option.

“The not proven verdict has served us very well for hundreds of years.

“It is being used as voter candy by politicians who think it will attract votes.”

Mr Findlay QC believes if a jury of 15 had the not proven verdict removed, it would be harder to reach a necessary majority decision.

“By doing away with not proven, it will make it more difficult to convict people.

“We have by no means a perfect criminal justice system in Scotland but it is admired around the world. Politicians would do well to leave it alone.

“Ms Sturgeon thinks that by jumping on this bandwagon, it will win her votes. It is shameless.

“Douglas Ross has also called for this, which is disappointing to say the least.”

The politicians – moves to end not proven

Removing the not proven verdict was unveiled as a pillar of the Scottish Conservative criminal justice manifesto.

Leader Douglas Ross said: “There is a disproportionate number of not proven verdicts in rape cases and that certainly doesn’t deliver for the victim and it still leaves the accused with an uncertain verdict.

“Guilty or not guilty is clear, not proven is too ambiguous.”

Nicola Sturgeon indicated on Sunday an SNP government may hold a review.

She said: “I do think it is time to look at the not proven verdict.

“The conviction rate for rape and sexual assault is shamefully low.

“I think there is mounting evidence and increasingly strong arguments that the not proven verdict is a part of that.”

Justice Minister Humza Yousaf has since confirmed a consultation.

The Greens, Labour and Liberal Democrats are all sympathetic to the notion of a two-verdict system.

Deputy Scottish Labour leader Jackie Baillie said: “We urgently need to reform our justice system to ensure it protects women and moving to a two verdict system would be one step in the right direction.”

Scottish Greens co-leader Lorna Slater said: “Having an ambiguous third option as a possible verdict in criminal trials is confusing for juries and unfair on both complainers and the accused.

“This verdict is disproportionately used in rape trials where often the victim faces a torrid time in court. That needs to end.”

Scottish Lib Dem leader Willie Rennie said: “It is clear that matters like not proven can’t be looked at in isolation.

“We have been working with victims’ groups and survivors to understand how to make things better.”