Paedophile hunters who use social media to snare sex predators could be putting children “at greater risk of harm”, according to charity NSPCC.

It is feared “well intentioned” groups which set up decoy accounts to ferret out groomers and abusers could jeopordise prosecutions and drive offenders further underground.

It comes after a 2021 trial at Perth Sheriff Court shone a rare spotlight on the inner workings of paedophile hunting group Forbidden Scotland, one of dozens of online groups operating in the UK.

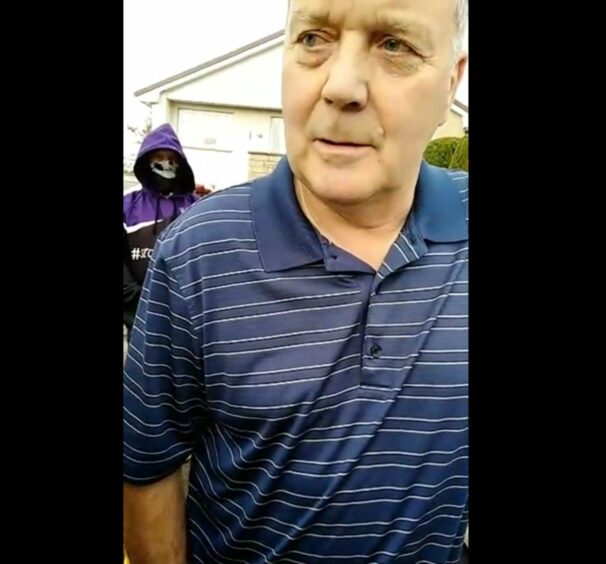

Railway worker James Kettles, 63, tried to convince a jury in September he sent a series of sickening messages to an online decoy – posing as a 13-year-old girl called Ruby – because he knew it was an adult and wanted them to reveal their true age.

But he was placed on the sex offender’s register for three years and ordered to carry out 250 hours of unpaid work after jurors rejected his claims and found him guilty of attempting to communicate indecently with a child.

Decoy operator Nicola Davidson told the court that her “Ruby” profile had snared hundreds of men in the two years since she began volunteering.

This was her first time in a court room, she said.

“All the others pled guilty, so they never went to trial,” Ms Davidson told the court.

“This is the first time I’ve had to give evidence.”

Recruitment process

She joined the group because she wanted to protect children online and “act as a barrier” between them and online predators.

She was given six weeks of training before she activated her decoy.

She explained the course involved role-playing sessions – with team members acting as abusers – and then a trawl through previous messages exchanges that led to successful convictions.

Miss Davidson said she followed a strict set of rules, including always stating the decoy’s age within the first three messages – “I tried to get it in as much as possible, maybe once a day” – and discussing nothing more explicit than “white underwear”.

“You are not allowed to send the first message,” she said.

“It always has to be the other person who makes contact first.”

The fake profile, with a digitally altered photo which made her look like a young teenager, was then posted on several social media platforms.

How groups track down their suspects

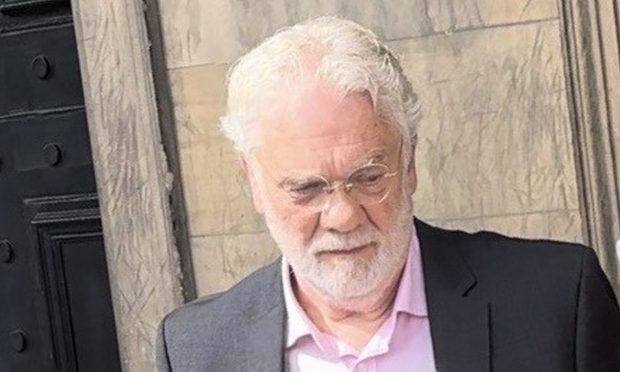

The group’s founder Glenn Stewart said that, after an incriminating cache of messages, images and videos was gathered, the team’s researchers would establish the suspect’s identity and address.

Mr Stewart, who set up Forbidden Scotland three years ago after people he knew became victims of sexual abuse, told the trial that electoral role websites such as 192.com and Tracegenie are used to draw up a shortlist of possible addresses.

In the case of Kettles, the team used Google Streetview to virtually walk around the streets and match them to the view from his living room window, which could be seen in his topless dancing video.

Eventually, the group will physically confront their suspect in what is known as a sting operation.

Days before, members will stake out the property, and may even knock on the door claiming they are looking for a lost parcel.

The team will call the police at the start of the sting, which will be broadcast live on the group’s Facebook channel.

Mr Stewart said: “We believe in exposure.

“We think that parents should know that someone like this is living near them.”

NSPCC warning over paedophile hunters

A 2020 study revealed about half of online grooming cases reported to Police Scotland are uncovered by online vigilante groups.

Many lead to successful prosecutions including several high profile cases in Tayside and Fife courts throughout 2021.

However, Andy Burrows, the NSPCC’s Head of Child Safety Online, fears groups could actually put police investigations at risk.

“We have sympathy for everyone who is worried about suspected abusers,” he said.

“We have sympathy for those who want justice for children who have been subjected to awful trauma and harm and who will feel frustrated that police can’t do everything.

“But despite the best intentions of these groups, their actions might actually put children at greater risk of harm.”

‘A really high risk’

Mr Burrows said: “They could potentially drive offenders further underground, and potentially jeopardise sensitive police investigations.

“There is a real risk they could cut across current police inquiries and that could lead to court proceedings being jeopordised.”

He said: “It means that these suspects may never have to deal with the consequences of their actions.

“That is a really high risk and one that people who are part of these groups really need to reflect on.”

Mr Burrows said he understands there is a “huge degree of concern” about online paedophiles and urged anyone with fears about an individual to alert police or the NSPCC helpline.

“The best thing is to let the authorities take over, so that the appropriate processes can kick in,” he said.

Police Scotland: Let us handle it

Police Scotland has said it does not condone the actions of paedophile hunter groups and urged people “not to take the law into their own hands”.

Detective Superintendent Martin MacLean, Police Scotland’s head of child protection, urged “caution against revealing the identity of suspected offenders as it can jeopardise the safety of individuals, their families and the wider public, as well as disrupt communities.”

This year, the likes of William Meek and William Rennie were sentenced at Tayside courts, after first being targeted by online groups.

In November, we reported suspected paedophile Andrew Clunie was believed to have taken his own life after he was confronted by a vigilante group at his home in Perthshire.