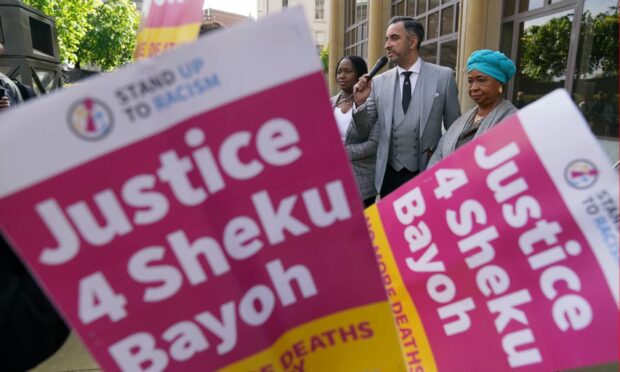

Another tranche of evidence has been heard in the Sheku Bayoh death inquiry.

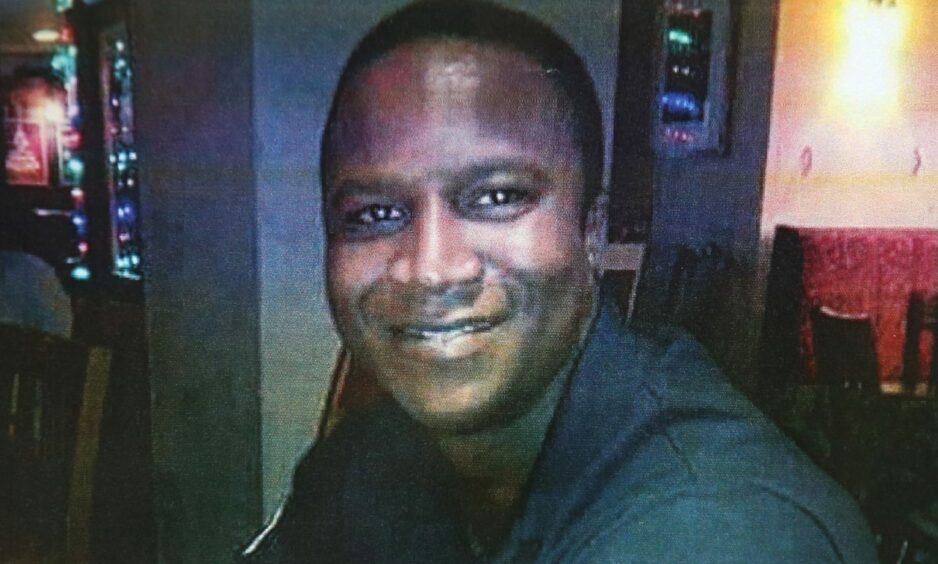

Mr Bayoh, 31, died after being restrained by police in Kirkcaldy on the morning of May 3 2015

The inquiry in Edinburgh is investigating the circumstances of his death, how police dealt with the aftermath, the subsequent investigation, and whether race was a factor.

The latest evidence, heard over the last three weeks, has examined police training.

‘Vulnerable’ family forced from home

The inquiry heard this week how detectives investigating the death “forced” a “vulnerable” family to leave their home without consent.

The inquiry has heard Mr Sheku partied with friends and took Class A drugs hours before he was reported by multiple witnesses, walking in Kirkcaldy and striking vehicles with a knife.

Officers went to the home of Mr Bayoh’s friend Zahid Saeed and spoke to his sister, Saadia Rashid, who was caring for her elderly mother and paraplegic brother and two young children, including a baby who was being breastfed.

On an earlier occasion, Mrs Rashid told the inquiry she repeatedly insisted police obtain a warrant but was told “they didn’t need one” and the family had to leave the house so it could be searched.

She said a plain-clothes officer “forced himself into the house” after intimidating her and the family were “forced” to leave and felt like “criminals with no rights”.

Mrs Rashid added they felt “vulnerable and victimised” and were so rushed she forgot a breast pump and medication.

Giving evidence on December 4, Detective Constable Gordon Miller, 54, said: “I’m sorry if she felt like that. It wasn’t our intention to make people feel like that.”

In a statement, DC Miller said he told Mrs Rashid: “Sometimes you do not need warrants, because it was a serious incident that had happened at that time the property had been seized, we’ve got to protect the forensic integrity of it.”

Mr Miller said: “She did ask for a warrant and I know it says there that we were pushy, abrupt and quite rude.

“At that stage because the family were so unhappy, we were expecting a police complaint to come in.

“We certainly weren’t rude or pushy in any shape or form.

“In these situations where people are likely to complain, you’re careful.”

The detective said he followed a “lawful order” from the senior investigating officer “to protect the forensic integrity… so if there was drugs within the property it couldn’t be disposed of”, citing common law powers.

He said a warrant could be sought retrospectively but could not explain why some senior colleagues said the family had consented.

“I don’t know why they thought consent had been given, it would have been pointless asking, we had fed back that the family were quite unhappy about having to leave the address.

“Why they’ve thought they were consenting to a search, you would have to ask them that.”

Property seized under ‘common law’

Police deemed the property to be a “secondary crime scene” and “presumed it would be drugs or a weapon or something”, the inquiry heard.

When asked what steps he took to ensure the family knew they did not have to consent to the search, Mr Miller said: “I don’t recall that I took any steps.”

He added: “They weren’t consenting as such, they were begrudgingly leaving, they weren’t happy to leave.”

Mr Miller said he recalled a householder being threatened with arrest if he attempted to enter.

When asked what authority he had to “restrain someone from entering the house”, Mr Miller said: “Technically, if it’s his household, there’s none to stop him coming in.”

He added: “We’ve seized that property under common law and we’re trying to protect it as best we can.”

He conceded there was not “authority” to “force” a family to leave.

Racism complaint

Police received a complaint the family were “thrown out into the street” and had been told they could not remain in a single room in the house, the inquiry heard.

Mrs Rashid said she believed they were treated differently “because we were Pakistani and Muslim”, and she “didn’t feel safe”, as a male officer stood outside her door as she got changed.

Mr Miller said by 7pm no alternative accommodation had been found for the family.

He also said that he learnt more about Islam from volunteering with Scouts than from police training.

A complaint was lodged on May 14, from Fife Islamic Centre, which said: “The people living in the house were thrown out of the house, (including a seven-week old baby and a disabled person), into the street without any explanation.”

No way to know extent of police training

A Police Scotland instructor told the Sheku Bayoh inquiry there was “no way of telling” what training officers “actually received” in the run-up to Sheku Bayoh’s death.

Inspector James Young gave evidence to the inquiry for the second time.

He was the national officer safety training (OST) co-ordinator for Police Scotland at the time of Mr Bayoh’s death.

Mr Young told the inquiry in a written statement a new training manual had come into use from 2013 to be used across all of the former legacy forces that made up Police Scotland to ensure there was consistency across the country.

Some trainers “preferred to use their own techniques” because they did “not agree” with the methods contained in the manual, Inspector Young said.

Senior counsel to the inquiry, Angela Grahame KC, took Mr Young through a statement from David Agnew, a trainer at the Scottish Police College at Tulliallan, in which he outlined the best practice approach to training.

Mr Agnew wrote students (trainee police officers) were taught to be aware of the signs of positional asphyxia and would be reminded because somebody can speak and shout, it did not necessarily mean they were able to breathe properly.

He wrote students would be taught to look out for behavioural changes such as suddenly stopping resistance and going limp and be mindful of where they were placing their hands and body weight when restraining a subject.

Mr Young said this was similar to his recollection of what new recruits should be taught.

Ms Grahame asked Mr Young about the training received by the officers who had been at Hayfield Road in Kirkcaldy, the day of Mr Bayoh’s death.

Police Constables Ashley Tomlinson, James McDonough and Kayleigh Good were all probationer officers and had received either initial operational training, or refresher training, in the six months since the day’s events.

Asked if they would have received the 2013 training, he replied: “For the refresher elements, there is no way of telling what training they actually received because… there was that disparity across (legacy) forces.”

Legal highs evidence

Dr Richard Stevenson, a consultant in emergency medicine at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, gave evidence about acute behavioural disturbance (ABD), previously known as excited delirium.

ABD would typically manifest as shouting and delirium, with a high temperature and possible violence.

The possibility of excited delirium affecting Mr Bayoh has been discussed previously in the inquiry, although Dr Kerryanne Shearer, the pathologist who examined him after he died, dismissed it as a significant cause of death because it is a psychiatric condition, rather than one that can be diagnosed through a post-mortem examination.

She confirmed Mr Bayoh’s was a “sudden death in a man intoxicated by MDMA and alpha-PVP whilst being restrained”.

The inquiry heard around 80% of cases of ABD brought to the hospital have been in contact with police before they arrive.

Dr Stevenson, lead medical adviser to Police Scotland, said ABD “only really started becoming an issue when the legal highs came on to the scene, or novel psychoactive substances.

“We never really had any experience of ABD and then the legal highs came on board and we were inundated with people with abnormal behaviours, so probably around 2015/ 2016.”

Legal highs, also referred to as new psychoactive substances, are substances which mimic the effects of drugs such as ecstasy and cocaine.

Dr Stevenson said: “We’ve had probably four or five that have died due to multi-organ failure.”

Asked by Laura Thomson, lead junior counsel to the inquiry, to describe what happened in these cases, he said: “When they come in to us they are lying and sometimes not moving at all but their bodies are rigid.

“They are extremely hot to touch and often we have to get fluids in as fast as possible but their kidneys and liver have been severely damaged by the ongoing agitation and the high temperature before they come to hospital and then even though we try to resuscitate them, they unfortunately don’t make it.”

Dr Stevenson told the inquiry dealing with a typical case of ABD can be “challenging” for medical staff and can be “frightening” as the patient may be violent.

He told the inquiry typical treatment would be to sedate the patient, often using ketamine, which would be administered as an intramuscular injection.

Mr Bayoh, 31, died shortly after his confrontation with police.

The inquiry, before Lord Bracadale, continues.