Michael Alexander looks back to how Courier Country celebrated VE Day in 1945 – and discovers that the end of hostilities in Europe brought “mixed feelings” for many people.

It was the day that Prime Minister Winston Churchill officially announced the end of the war with Nazi Germany.

In a message broadcast from the Cabinet room at Number 10 Downing Street at 3pm on May 8, 1945, the former Dundee MP announced to an expectant nation that the ceasefire had been signed the previous day at the American advance headquarters in Rheims.

He paid tribute to the men and women who had laid down their lives for victory as well as to all those who had “fought valiantly” on land, sea and in the air.

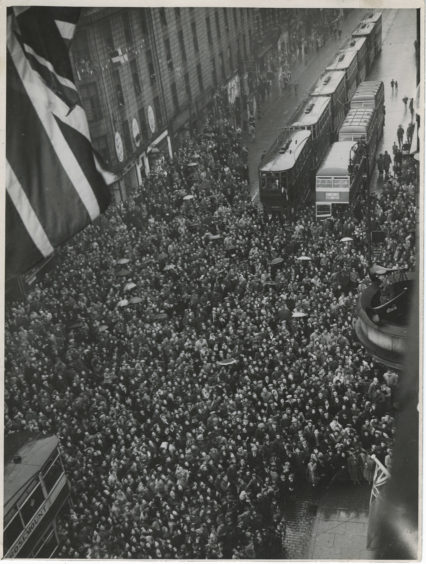

The news prompted huge celebrations and street parties.

Huge crowds – including many dressed in red, white and blue – gathered outside Buckingham Palace in London.

They cheered as King George VI and his family, including Princess Elizabeth (the current queen) and Princess Margaret, came out onto the balcony to greet everybody.

The two princesses were allowed to leave the palace and celebrate with crowds, although they had to do it secretly.

The future Queen described it as “one of the most memorable nights of my life”.

But VE Day was also a moment of great sadness and reflection as millions of people had lost their lives or loved ones in the conflict.

The war against Japan would continue until August and lots of people were being kept as prisoners of war abroad.

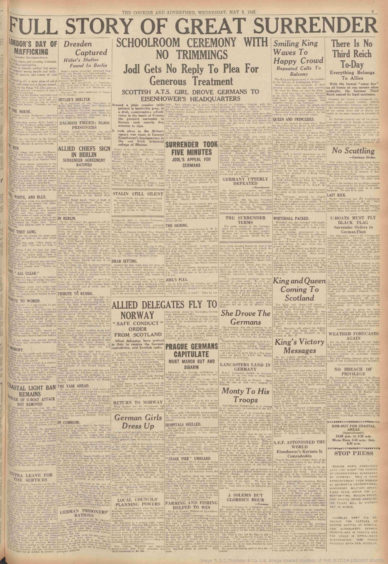

Under the headline Full Story of Great Surrender, The Courier of May 9, 1945 gave a detailed account of Nazi Germany’s “final humiliation”.

“Around a plain wooden table painted in battleship grey, in a drab, commonplace schoolroom in the heart of France, the greatest surrender in history took exactly five minutes to sign,” The Courier report said.

“It took place in the 30-footsquare war room at General Eisenhower’s headquarters in the red brick industrial college of Rheims.

“Seated at the table were three American, three British, three Russian, and three German officers… “When they saluted they used the regular German military salute and not the National Socialist salute.

“Around the blue walls were war maps on which the Germans could well see the hopelessness of, the military situation.

“There were also secret charts showing the current day’s operations, casualty lists, records of stores, and communications.

“In the centre of the room was the plain, uncovered, and cracked table, 20 ft. long and 8 ft. wide, painted a battleship grey.

“Each delegate had pencil and a pad of paper before him. There were china ash trays at each place, but they were superfluous as nobody smoked.

“Altogether it was a drab setting.”

The Courier told how across Britain there was an “overriding mass sense of relief of a job well done and a danger passed”.

A national holiday had been declared for May 8 1945. In the morning, Churchill had gained assurances from the Ministry of Food that there were enough beer supplies in the capital and the Board of Trade announced that people could purchase red, white and blue bunting without using ration coupons.

However, The Courier told how “one of the last dramas of the European war” had played out off Fife on the night of May 7 with two ships – the SS Avondale Park and Sneland 1 – sunk by a U-boat off the East Neuk.

It also reported that Dundee would remember VE Day celebrations with “mixed feelings” under the headline “Cheery Day has queer start: factory chaos, then dancing in streets”.

The report described the government’s “belated announcement” that May 8 was to be a holiday as “bungled”.

This resulted in “chaos” at the city’s mills, factories, shops and offices when hundreds who turned up at their workplaces found they had to go home again.

“The position at Caledon Shipyard was example,” The Courier said.

“Two hundred men followed instructions which had been given earlier, only to find they were wrong.

“The Government had bungled it. Women who went to the post office to draw their allowances and pensions found the gates up.”

Despite the bad start, however, the city made the most of the occasion – though an afternoon breakdown in the weather dampened spirits temporarily.

“In the forenoon thousands went to the city centre where the decorations were a delightful show,” The Courier said.

“Yet it was Bernard Street that captured the decorative honours of the day, with a profusion of flags that almost obliterated the tenements of a street which has a high reputation for patriotism.

“Overgate was a good second, with a display which included three obsolete flags of the Papal State.

“A large crowd gathered in City Square in the afternoon to listen to the Polish-Military Band.

“Heavy rain drove the bandsmen to shelter, and torrential shower later dispersed the crowd. But only for a little.

“When the skies cleared the young folk returned to the square for dancing to the accompaniment of pipe bands. Throughout the evening they enjoyed themselves to their hearts’ content, the eight-some reel being particularly popular, and thousands were looking on.

“The steps in front of Caird Hall were packed, and people were watching the animated scene from windows and roofs.

“Even when the band went home the dancers continued. It was a continual babel of sound, with intermittent cracks of fireworks. And so on it went until the early hours of the morning.”

The report went on to describe “bonfires blazing”. Kemback Street and Lily bank Road had really big ones. Squibs and rockets were going off “here, there, and everywhere”.

Servicemen of different nationalities “were fraternising with the citizens in a joyful camaraderie.”

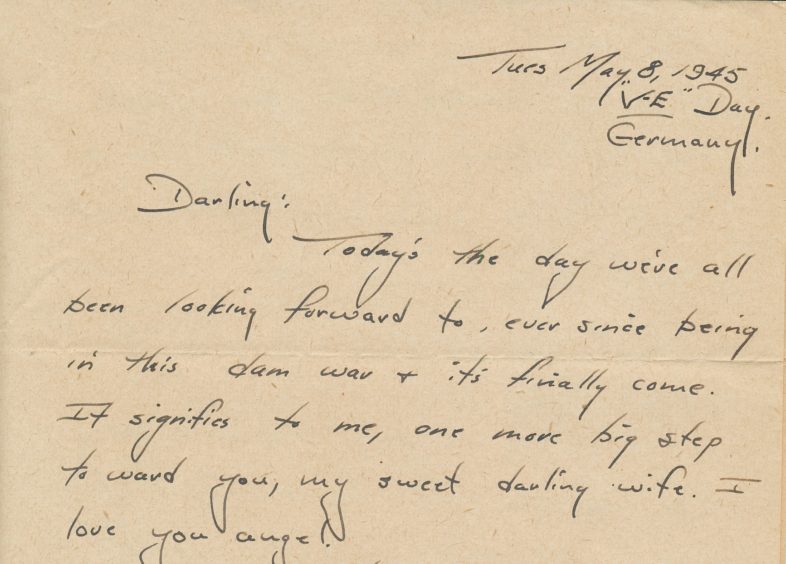

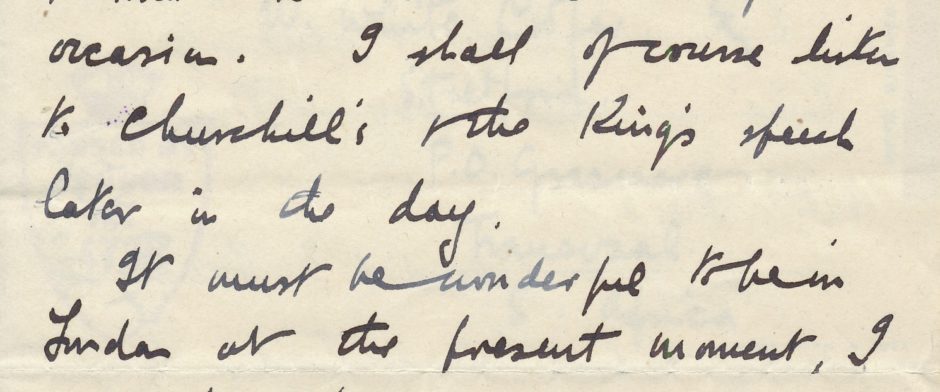

Dundee journalist and historian Norman Watson owns several unpublished Second World War letters sent on VE Day from the frontlines which contain remarkable accounts of the first emotional handshakes, the relief of those exposed at the Front, a sense of loss for comrades who fell near the finishing line, the contemplation of what had happened – and, free from danger, the urgency to write home to tell all they had survived.

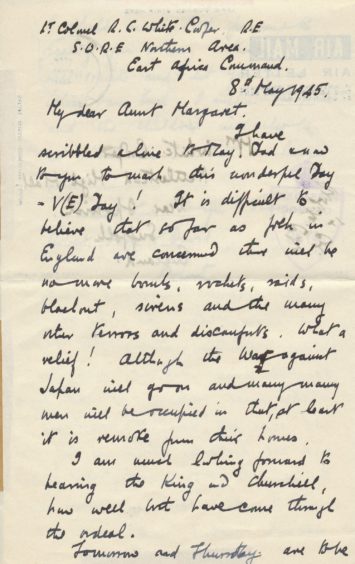

Typical is a letter from Lieutenant Colonel Rupert White-Cooper of the Royal Engineers to his Aunt Margaret in Suffolk.

Sent from Nairobi and endorsed ‘East Africa Command, 8 May 1945, the letter captures history in the making: “I am much looking forward to hearing the King and Churchill; how well they have come through this ordeal … no more bombs, rockets, raids, blackouts, sirens and the many other terrors and discomforts. What a relief!”

Another letter, from Lieutenant Herbert Fulweiler of the US Army to his mother in Kentucky, was penned on the evening of VE Day and provides an eyewitness account of the final action of the war: “The best thing about this whole day was the fact that we knocked down two Jerries on the last day. We’re pretty happy about it.” Lieut Fulweiler’s 119th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion is credited with firing the last official shots by General Patton’s Third Army and may have been part of the last Allied action prior to the German surrender.

A further letter, from a medic, highlights the euphoric scenes in Britain as citizens rose to the challenge of celebration.

“Many of the pubs were drunk dry and they said half a million persons had to sleep out of doors because they missed the last bus home!” The writer adds more soberly: “I think they had genuine cause for their celebrations…the relief of blackout and freedom from bombs and air attacks.”

Mr Watson said that mail was the soldiers’ connection with the outside world, their link to families, friends and past lives. And at home, letters were the longed-for confirmation of life – literally – from loved ones often in advanced positions.

“A visit by the brigade postman brought soldiers their only reminder of civilian life,” Mr Watson said.

“Among men of all ranks the arrival of the mail was looked forward to with genuine eagerness. But for the historian, these precious letters allow access to a very human level of the war during this dramatic and decisive time.

“Through reading these letters, we feel we know the letter-writers personally, thus contributing much to our understanding of their exceptional experiences as the war ended in 1945.”

Reflecting on the 75th anniversary of VE Day, Derek Patrick, Associate Lecturer in History at St Andrews University said that understandably there’s a “huge resonance” attached to May 8, 1945, and rightly so.

But what strikes him when reading and hearing about contemporary experiences of the day was that while people celebrated, there was also considerable reflection.

People became aware of what had been lost, but also aware of the fact that the war wasn’t over – they were still fighting in the Far East. Any kind of celebration was perhaps tempered a wee bit by that.

Some PoWs were starting to return home from Europe by VE Day, but it would take a long time for others to be demobbed and a long time for the battered economy to get back to anything like normality.

Dr Patrick said that because the announcement of the German surrender came through on May 7 1945, some places found themselves in “limbo” with people wanting to celebrate but having to wait until the formal Churchill announcement

“Some places do break out into sporadic celebration,” he said.

“There were reports of Scone and that taking to the streets. But most places like Edinburgh for example were described as being quite reserved. Glasgow is totally different. It seems to spontaneously erupt into celebrations. It was reported it went ‘daft with joy’.

“You tend to find Perth and Dunkeld are all illuminated with bonfires. People suddenly produce fireworks – I don’t know where they’d been storing them! There was a roaring trade in Union flags and red white and blue rosettes.

“There’s various concerts put on by local groups. Local pipe bands at Leuchars for example – troops are stationed there. There’s dances, a lot of Norwegian and Polish troops stationed in the areas – particularly Poles. They play a full and active part in the celebrations.

“It’s very similar in some respects to what went on in 1918.

“In Perth the police talked about how most people were orderly and sober. The biggest problem was people going out and stealing flags from other peoples’ shops!

“Bonfires were also quite big. Every town and village would have a bonfire. They were burning effigies of Hitler, Mussolini and wooden swastikas. They had that in places like Scone and Perth.

“There were also more formal celebrations like church services being held.”

Dr Patrick said it was “interesting” that during the current Covid-19 crisis, some politicians and some sections of the media used “Blitz spirit” type language. If any comparisons could be made, it’s the way communities have come together to help the vulnerable.

But he’s wary of direct comparison between coronavirus and the war as these are “very different times” with considerable uncertainty at this time as to how and when a day will emerge when “victory” over the virus has been secured.