Michael Alexander hears how a single entry in a 118-year-old Arctic whaling log book, and eyewitness accounts buried in The Courier archives, led to the discovery of a long lost Dundee ship wreck in the dangerous waters of the Canadian Arctic.

It wasn’t unusual for The Courier of the late 19th and early 20th centuries to report in great detail the exploits of Dundee’s whaling fleet when they returned home after months away in the perilous waters of the Arctic.

But when the Diana berthed in Victoria Dock on November 3 1902 with her “excellent” haul of five whales, 18 bears, three walrus and several seals, subsequent newspaper reports took a particular interest in the fact that she was carrying extra passengers – the crew of another veteran Dundee whaling ship called the Nova Zembla which had been wrecked off the remote coast of Canada’s Baffin Island six weeks earlier.

Testimonies revealed that the Nova Zembla – a 140ft barque-rigged steam whaler under the command of experienced first mate John Clooney – was forced to run for shelter during an intense and blinding snowstorm.

However, at 10.20 pm on September 18, 1902, the crew were startled by the sudden lurch of the ship and the painful sound of splintering timbers.

Nova Zembla was aground on a reef, a mile south of the harbour entrance, 300 yards from shore.

Dropping anchor and battered by the ferocious storm, the masts were the first to be ripped off followed by the engines thrust up through the splintering deck.

By the following morning, the crew had managed to launch some of their six whaling boats and make it to shore. Those left on board witnessed at first hand their shipmates run up and down the beach to keep warm. A party was sent to row around the rocky peninsula to seek assistance from other ships that may also have been sheltering from the storm.

To their relief, fellow Dundee whalers Diana and Eclipse were safely at anchor, and all 42 men aboard the Nova Zembla survived and made it home to share their tales.

Interviewed by The Courier back in Dundee, a Diana crew member recalled the “wicked time” as they sought shelter and came across the Nova Zembla in its “sad plight”.

“It was up to the portholes in water,” remarked Second Mate Taylor.

“The ship was doomed, but the Diana’s crew risked much in rescuing the whalebone secured by the unfortunate whaler,” the report added.

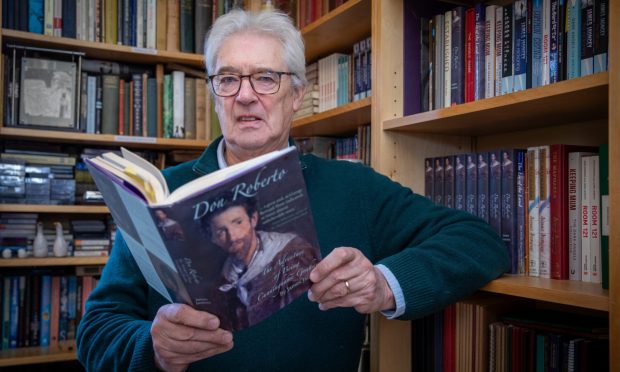

Until two years ago, historical climatologist Dr Matthew Ayre of the Arctic Institute of North America at Calgary University, Canada, had never heard of the Nova Zembla.

The Tynemouth-raised Sunderland University geography graduate, who obtained his PhD in 2016, was studying the surviving ships’ logbooks of the British Arctic whaling trade to learn about changes in sea ice for his post-doctoral research.

The logbooks also provide an “amazing window” into the lives of those who ventured to the icy edges of the known world.

It was in March 2018 while working on the logbook of the Diana’s 1902 voyage from Dundee to Baffin Bay, however, that he came across a single entry that came to dominate his thoughts. It read: “One of the Nova Zembla’s boats came alongside and reported to us that the Nova Zembla was ashore a little to the southward, and that water was up to the ‘tween decks’.”

Intrigued to know more about what had happened and whether the wreck was still there, he diverted the course of his research – a pique of interest that would ultimately lead him to The Courier newspaper archives then on to the perilous waters of the Canadian Arctic where, after 116-years, he would discover the lost wreck itself!

“When I read the logbook reference and started looking into it, I discovered this bunch of newspaper reports that gave first hand accounts of what happened,” said Matthew, 33, who was due to film a documentary in Dundee this month until coronavirus restrictions intervened.

“At the time the Dundee whaling fleet was famous – the last Arctic whaling fleet in Britain – so there was always a big fanfare when they left and the newspapers were always eager to find out how successful they were when they returned – including The Courier.”

After mentioning the fate of the Nova Zembla to his Arctic Institute and underwater archaeologist colleague Dr Mike Maloney in the pub, the pair sat hunched over a chart trying to plot a possible location for the wreck based on newspaper interviews with the crews who returned.

Still regarding the search as something of a “pipedream”, they pinpointed a beach and hypothetical search area where the ship might have gone down.

When they looked on Google Earth, however, their excitement grew exponentially when they spotted a grainy “anomaly” 300 yards off the beach, 140 feet long, 30 feet wide and ship-shaped. There were even three lighter spots that looked like masts.

Persuading the Arctic Institute director that they should pay $500 for a high resolution satellite image of the site, they were disappointed when it showed the anomaly had disappeared. “It was most likely an iceberg,” said Matthew.

However, when a coastal geomorphologist colleague then offered to have a closer look at digital imagery around the area, he came up with a different anomaly further north that was still within the realms of the search zone.

Again it showed the potential dimensions of a ship but crucially this one had a sediment plume coming from it – a possible sign that the object had been on a certain heading before becoming submerged. Could this be the wreck of the Nova Zembla?

Within two months, Matthew and his team secured expedition support from the Royal Canadian Geographic Society with additional funding from the Arctic Institute of North America.

With a tight budget, they persuaded a cruise company to let them board a passing liner which would drop them off for a tight seven-hour search window at their location. Unable to afford sonar equipment, they had to make do with a fish finder, purchased a drone and were loaned a small remotely operated vehicle (ROV) by Deeptrekker.

Six months after reading his first account of the Nova Zembla, Matthew could scarcely believe he was cruising the North West Passage then traversing down the north east coast of Baffin Island, seeing the landscape of the whalers for himself.

Anticipation was running high. However, within one hour of launching their Zodiac from the cruise ship in terrible conditions at 5am, their hopes were dashed when the anomaly spotted on the satellite image turned out to be nothing more than a massive underwater ship-shaped rock.

It was a devastating blow. Having forgotten his thermals in the excitement of the expedition and as they battled a strong cold wind and heavy swell, Matthew became increasingly deflated as they ‘mowed the lawn’ using the fish finder to scan an area of boulder-strewn reef where they thought the ship might be.

They knew they must be in the right area as all the historical descriptions from the crew fitted.

Then, with just an hour left before they had to return to the cruise ship, an incredible breakthrough.

With binoculars trained on the shore, they spotted something that looked suspiciously like driftwood on the beach. To get driftwood in this part of the Arctic is extremely rare.

Buoyed by renewed expectation, they launched the drone.

But almost immediately it was clear this was no driftwood – it was the mast of a ship complete with iron fittings, alongside a bit of bow, block and tackle, a yardarm and a rib timber with iron rivets– very clearly pieces of a sizeable wooden sailing ship.

With only four minutes of battery power left on the drone, and unable to go ashore because they did not have permits to step onto Inuit land, they grabbed 25 aerial photos. They also managed to grab a few moments to launch the ROV around 300 yards offshore.

Little could they imagine that when they reviewed the footage back on the cruise ship, they would catch a glimpse of an anchor and chain on the seafloor. There could be little doubt. This was the long-lost wreck site of the Nova Zembla!

But the 2018 discovery had only found limited evidence. They had to go back.

After overcoming funding issues, and still on a tight budget, the team returned in summer 2019 – this time with thermals and this time with the right permits and more equipment.

Relieved to find that after a 20-hour transit, a forecasted storm had not materialised and that polar bears seen in the area the day before had disappeared, they picked their way through the reef and stepped on to the beach.

“We get ashore and instantly we can see there’s just ship everywhere,” said Matthew.

“This included ornate carved pieces we later confirmed through an 1884 painting of Nova Zembla that they came from the bow.

“Prioritising quickly because of the weather forecast, the drone pilot sets up to do an aerial survey and we are walking the beach, photographing, taking notes – thousands of pieces.

“We’re walking the beach, photographing what we could. Taking notes.

“As we are walking down the beach we find a 60 feet section of hull sticking out of the sand. We find the masts all intact on the beach.

“We find the remains of a whaling boat on the beach still with paint on it – weathered but identifiable.

“We spent the next eight hours on the beach walking and photographing in almost total disbelief.

“When we went down to the next beach to see if we could find anything else, it was fairly incredible – we found a perfectly intact oar from one of the whaling boats above the high water mark.

“It was amazing that these things had been lying there for 117 years almost untouched.”

Several days later as the cruise ship continued on its way in the teeth of the forecast storm, Matthew couldn’t hide his elation and amazement that information gleaned from reports in old Dundee newspapers had helped him pinpoint the site of the first identified historical British whaling wreck to be discovered in the Canadian Arctic.

Going back to his climate research, it had been Matthew’s intention to return to the region for an ambitious archaeological investigation of the wreck this summer.

But with that on hold for the time being, it’s given him time to investigate the possible location of another wreck he’s read about – a reference in an 1899 diary to the Dundee-built whaler Eagle which sailed out of St John’s, Newfoundland, and was abandoned in 1893 after taking in water.

With 220 wrecks of British Arctic whalers thought to be on the seabed around Svalbard, Greenland and Canada, and a number of amazing cultural links between the Inuits and Dundee – including the graves of Dundee sailors on Baffin Island – Matthew hopes to work with the local Inuit population around Baffin to “reconnect” the history.

He’s particularly fascinated by the story of an Inuit called Olnick – as featured in The Courier earlier this week – who was well known to the whalers and even asked to accompany them back to Dundee in 1878 to see where they were from.

“He became a bit of a minor celebrity in Dundee,” said Matthew.

“He had an audience with the Prince of Wales, goes back to Baffin and continues to lead a group of 40 people on an island next to the fjord where Eagle is and Nova Zembla ends up.

“He was known for salvaging wrecks. It was reported he salvaged the wreck of the Ravenscraig out of Kirkcaldy.

“But when he died in 1900, his son in law took over and the group moved south. That explains why when Nova Zembla wrecks two years later nobody salvages it.”

*As his research continues, Matthew Ayre would like to hear from any families connected with the Dundee whaling industry who might have stories to share. He can be contacted via matthew.ayre@ucalgary.ca