Michael Alexander speaks to Edith Windsor-Stokes whose great grandfather Charles Kasaja Stokes was adopted by Minnie Watson, the Dundonian teacher who helped lay the foundations of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa in Kenya.

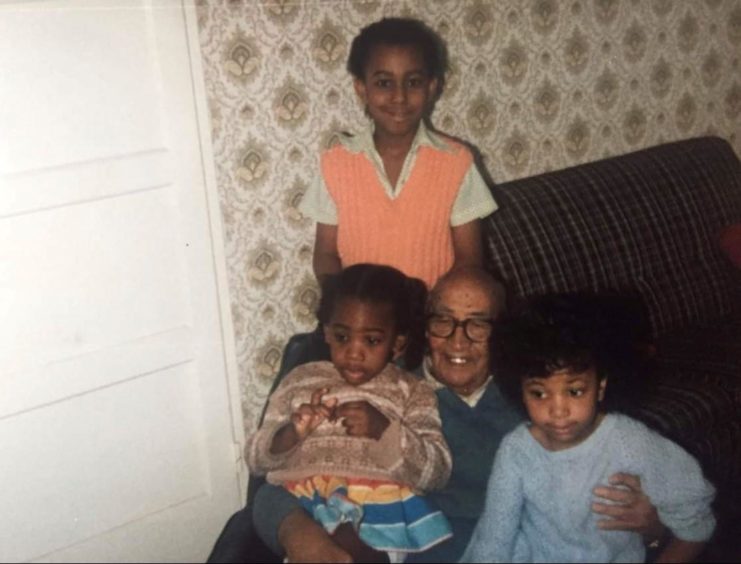

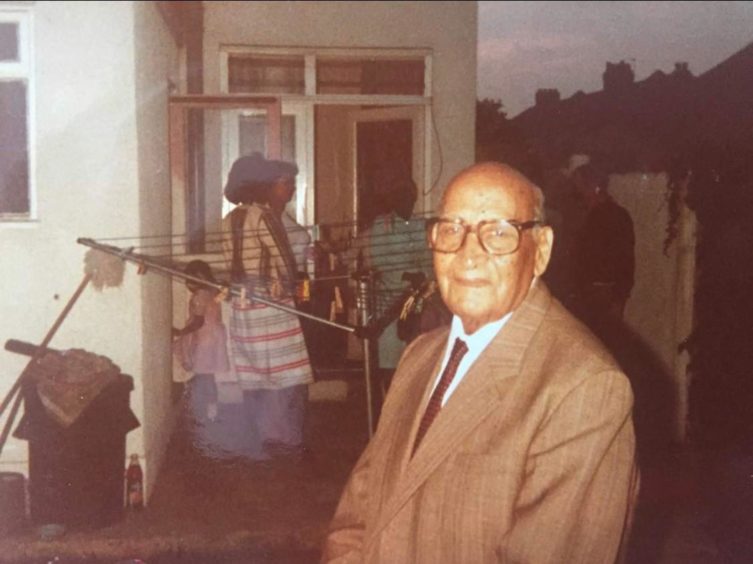

Amongst a collection of photographs owned by the family of Tower Hamlets school teacher Edith Windsor-Stokes is a particularly poignant one of her as a little girl sitting on the knee of her late great grandfather Charles Kasaja Stokes.

Gazing at the image transports the now 38-year-old mother of four back to a time when, as a child, Charles would visit the extended family around London from Uganda – a country to which his remains were returned and laid to rest next to his wife Sarah after he died from cancer in the mid-1990s aged 99.

To this day, Charles’ influence lives on through the life lessons he taught Edith, her sister, cousins and older relatives about family, education and health.

As the years have gone by, however, Edith has been discovering more about his remarkable backstory and his strong connections with Dundee.

Following the death of his father at the hands of Belgian colonialists, Charles was adopted by Minnie Watson – the Dundonian teacher and Kirk missionary who helped lay the foundations of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa in Kenya.

Minnie took many children under her wing and Charles lived with her family in Dundee for a time and attended Morgan Academy.

In an interview with The Courier from her home in Chigwell, Essex, following on from October’s Black History Month, Edith explained how they always knew aspects of his Scottish connections.

He spoke about the fact he had been in Scotland and would “do riddles with a Scottish accent” which were “really funny”.

However, it was only relatively recently that Edith and her family learned from a 2017 Courier feature that letters existed from later in life between him and Minnie who he regarded as his “second mother” and even named his first daughter after her.

He “compartmentalised” his life and while there were stories that he shared with his family, he kept bits to himself – leaving Edith’s gran, who was close to him, “shocked” as she had no idea the letters, recently found in Dundee, existed.

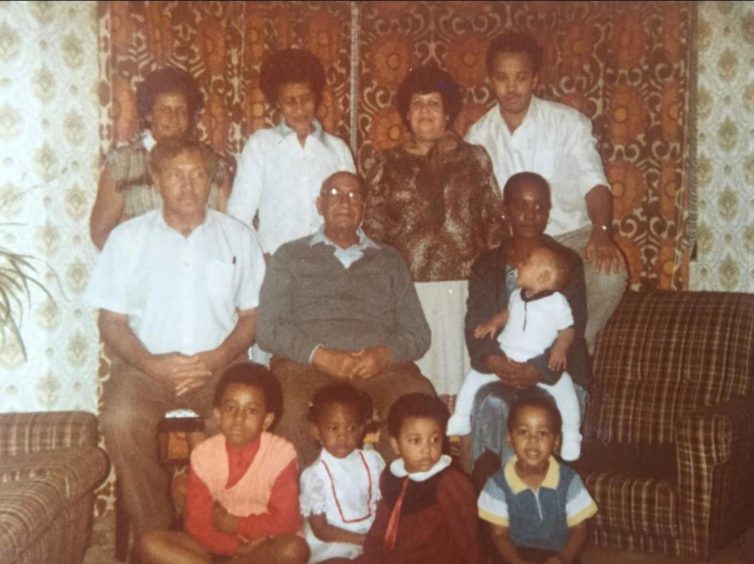

“I grew up in a household full of women who were very much about roots, your family, togetherness, and the extended family,” explains Edith, who grew up in Newbury Park, Essex.

“Grandpa Charles would travel back and forth to England from Uganda. There was a lot of influence – him being a very dominant male figure for us.

“We learned a lot about Uganda, a lot about his way of thinking – that education is important, health is important. All those things were true for all of us.

“From what we were told he stayed in Dundee for a time. It was really more about his academic period of study – primary going into secondary school.

“But we don’t know anything else in terms of what happened in Dundee. That’s why once Covid is over, we want to visit.”

Most people recognise Presbyterian missionary Mary Slessor as one of Scotland’s most famous daughters.

But she wasn’t the only “courageous” Dundee woman who made a dramatic and lasting impact on generations of people in Africa.

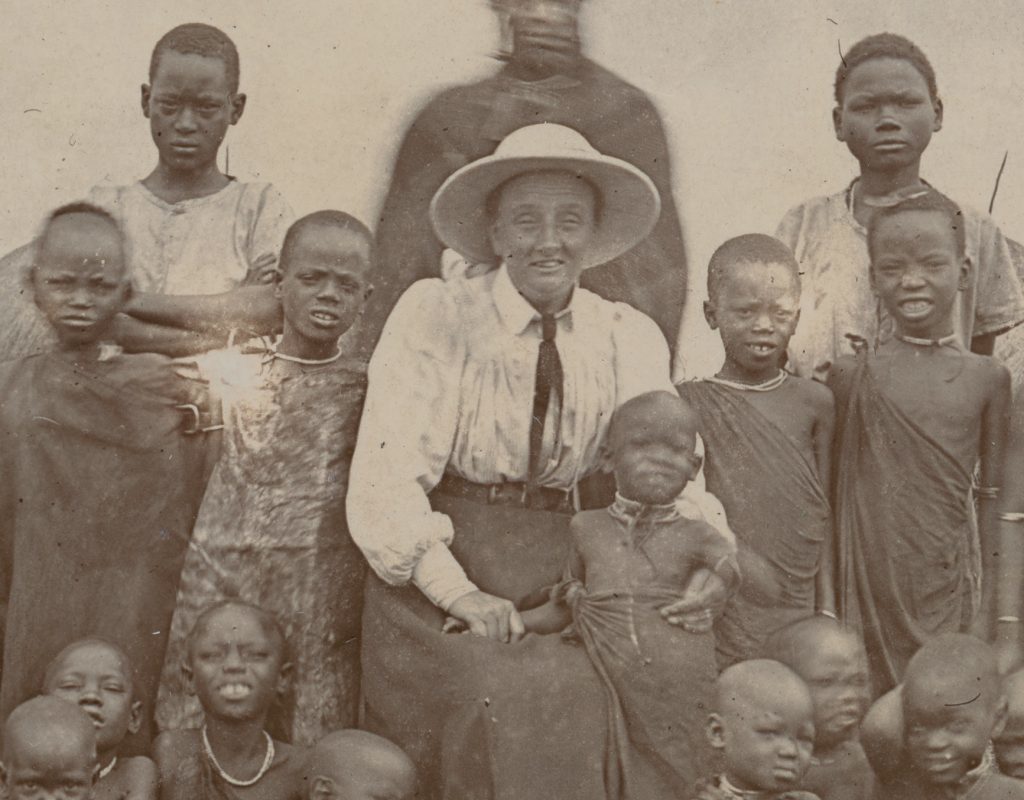

Minnie Watson, the daughter of a ship captain, was the first female Presbyterian Missionary in Kenya.

It was a world away from Dundee and the teacher endured extreme hardship – drought, famine and disease – to fulfil her mission of spreading the Gospel.

Minnie helped lay the foundations of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa (PCEA) which today has around 3.5 million members and runs a network of schools, hospitals and universities.

Born in 1867, she followed her fiancé, the Rev Thomas Watson, who was also from Dundee, to the former British colony in 1899 after he established the Scottish Mission in Kikuyu.

They soon married, but barely a year later, he died of pneumonia leaving the “devoted” 32-year-old to assume responsibility for the project.

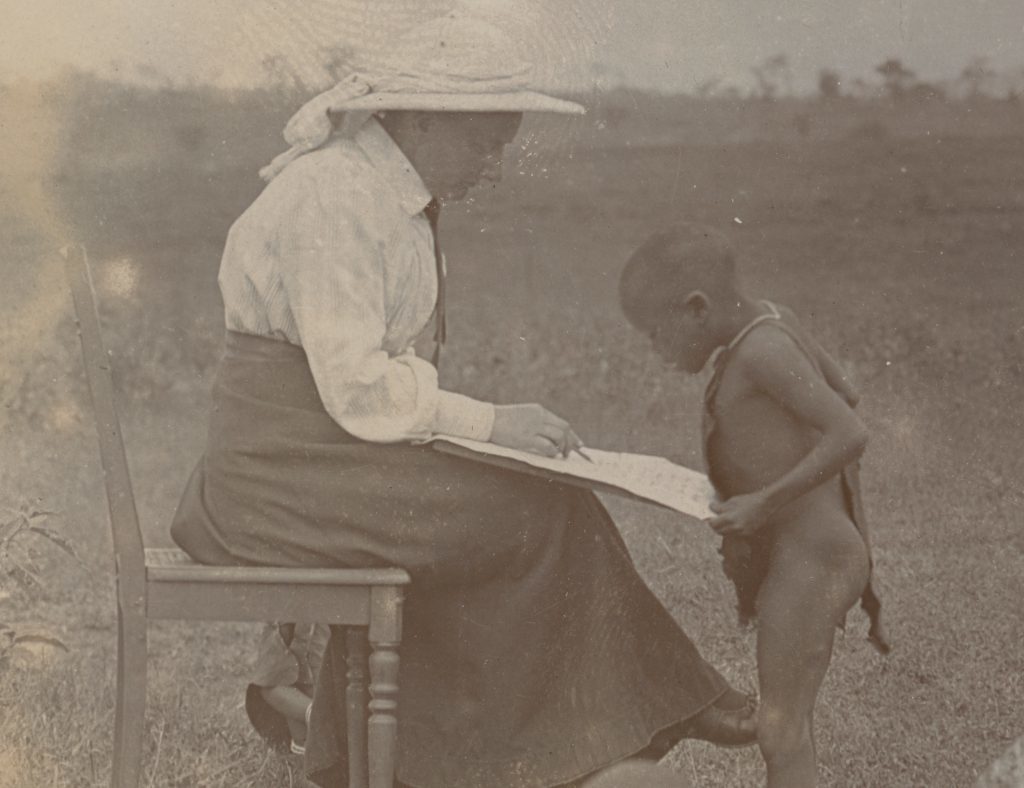

Education and welfare was Minnie’s primary focus and she established an extensive network of Mission Schools for girls and boys.

Kenya’s first President Jomo Kenyatta, father of the current President Uhuru Kenyatta, is a former pupil and was baptised in Watson-Scott Memorial Church.

It was prefabricated in Scotland at the turn of the 20th century and shipped 7,150 miles to Kikuyu.

The Scottish Mission was originally funded by Christian directors of the Imperial East Africa Company but was taken over by the Church of Scotland 12 months after Mr Watson died.

Minnie, who was head teacher of the Mission Schools system, was described by former pupils as an outstanding Christian role model – always loving, humble, patient but strict when necessary.

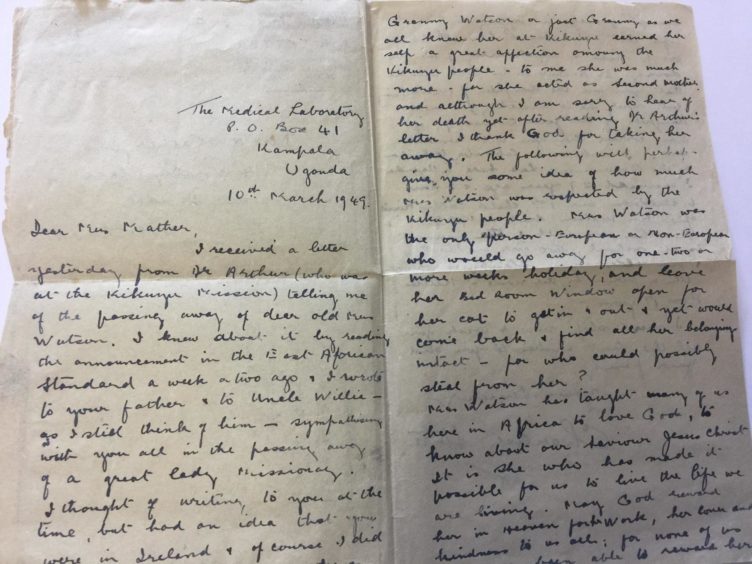

In 2017, however, fresh light was cast on her story when handwritten letters, documents and photographs that belonged to Minnie which had been gathering dust in a Dundee cupboard for nearly 70 years were gifted by the missionary’s great niece, Paddy McFarlane, to the National Library of Scotland.

As well as adopting Charles Kasaja Stokes from the Scottish Mission Station, she also adopted John McQueen, and brought them both back to Dundee in 1907.

They stayed with her mother at the family home in Wortley Place for four years and attended nearby Morgan Academy.

The letters showed that Charles, who was 11 when he returned to Kikuyu in 1911, regarded the missionary as his “second mother” and named his first daughter after her.

Minnie returned to Dundee in 1931 and spent the rest of her life living in a house in Wortley Place, aptly named Nairobi, until her death in 1949 at the age of 81.

Her ashes were returned to Kikuyu where they are buried next to her husband’s remains in a graveyard close to a church named in their honour.

The grave is marked by a large stone Celtic Cross, and the now faded inscription on the memorial stone once said: “They brought the light of God to the Kikuyu people.”

History records that Charles never knew his father. Charles Henry was arrested in January 1895 by the Belgians, for trading arms with their colonial enemies – Britain and Germany.

In a botched trial, Charles Snr he was convicted and sentence to death by hanging – just a few months before Charles Kasaja was born.

Charles may have now been gone for around 25 years.

But Edith is still learning about her great grandfather and is determined to find out more about his Dundee and Uganda links, where he trained as a medical technician.

What she does know is that while in Uganda, he met or he was introduced to her gran’s mum Sarah Wilson, who was also a mixed race child.

Charles’ daughter – her great aunt Edith who she was named after – then came over to England under a teacher training programme scholarship to Cambridge.

When Charles visited on three month trips, he would stay at their house and visit all the aunts. Later, she learned later, he would travel over from Africa to get cancer treatment.

Edith has fond memories of Charles teaching her how to tie her tie on her first day of school – a memory she found quite emotional when her oldest son, who’s now 14, started school and she did the same.

With Charles’ descendants living as far afield as America, Australia, Uganda and England, however – and with many working in the fields of health and education that meant so much to him – Edith said his legacy lives on stronger than ever.

“They’ve all in some way been influenced by the same things that he really tried to ensure in some way were important and crucial for life – studying hard, doing well, family and making sure family was always connected,” she adds.

“The land that he had in Uganda – most of that family still live there and are operating there. If you say you’re ‘Stokes’ in Uganda, people know who that is. It’s very well known.

“‘Oh, that’s Charles’ family’. Because of it being a multi-racial family, there is a clear distinction between them and most people in Uganda.

“It’s very visible that his legacy has lived on. We are really proud of that. That’s why I held on to that name as well because I’m so proud of it.”

Edith says the church also continues having a strong influence on the family.

She adds: “My grandma is very religious and my aunt Edith – out of all the children, I think, both are very much the frontrunners in really embedding spirituality and talking to us about our connection to God and making time to pray, to do all the things that we’ve got to do.

“It’s part of our family’s character, our nature, our moral compass.

“That’s something can all be traced back to Charles and to the influence of Minnie Watson from Dundee.”