The story of Dundee’s rich and varied history can be told through its buildings, but sadly many of the city’s structures are at risk and crumbling.

From the silent skeletons of old mills to the clean lines of Art Deco architecture, 44 of the city’s properties are considered to be in danger.

Scotland’s Buildings at Risk register seeks to identify buildings across the country which have historic or architectural merit, and are damaged, derelict or facing destruction.

Often sites that meet the criteria are listed or in a conservation area, empty, neglected or have been targeted by vandals.

We take a closer look at eight of Dundee’s most interesting buildings and what has happened to them.

Roseangle: then and now

Risk rating: Moderate

Condition: Poor

The faded glory of number 2 Roseangle, a vacant villa near the waterfront, gives little inkling of its gruesome past.

The B-listed Georgian house was built around 1815 with a grand doorway featuring Doric columns.

Later opulent additions in 1880 included the porch, balcony, mosaics and plasterwork.

But rather than being renowned for its lavish construction, it’s better known as the murder house.

The period property became notorious after it was the scene of a horrific double murder in 1980.

Retired doctor and pillar of the community Alexander Wood, 79, and his wife Dorothy, 78, were bludgeoned to death in their basement kitchen by an intruder.

Their dismembered bodies were only discovered when students saw them through the window as they went to retrieve a football from their garden.

The callous crime was carried out by psychiatric patient Henry John Gallagher who fled to England, where he killed again before being incarcerated in Broadmoor Hospital.

The property was leased to students for a number of years before falling into disrepair and it joined the buildings at risk register in 2010.

Windows which once had panoramic views over the Tay are boarded up, while ivy strangles the stonework.

Plans to turn the villa into a restaurant commenced in 2018 with some improvements carried out.

But the property returned to the market and has continued to slide into decay.

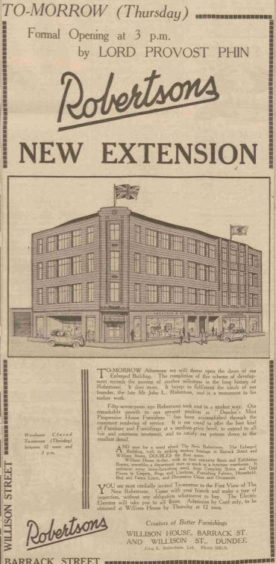

Willison House: then and now

Risk rating: Moderate

Condition: Poor

With its white exterior, metal window frames and stepped, linear brickwork, Willison House is unmistakably Art Deco.

Better known as the old Robertson’s furniture store, the landmark Art Deco facade was built in 1934 before it was extended in 1937.

At the time, a report described the new addition of a “majestic corner entrance” and extra windows which created “space, airiness and abundance of light”.

The extension enlarged the floorspace by a third, while the drab streetscape gave way to the latest floodlighting technology.

The Barrack Street premises were illuminated with “exceptionally strong lamps which throw up the white purity of the surface in the night-time, while during the day the glint of the sun catches its snowy whiteness”.

At the cutting edge of modernity in the 1930s, the only hint of the firm’s Victorian heritage was a wrought iron sign above the terrazzo entrance reading ‘Willison House, established 1880’.

The family firm occupied the B-listed building until Robertson’s fell into administration in 2011, shutting up the shop with the loss of 16 jobs.

In the last 10 years, the once sophisticated building has become increasingly dilapidated.

Cracks have appeared in its formerly pristine cladding, windows have buckled and there has been water damage.

Proposals to turn the site into student accommodation were turned down in 2017, and Dundonians launched a petition to see the Art Deco exterior saved in future development plans.

In 2018 consent was given for the building to become a boutique hotel and bar, knocking down large parts of the original structure, but maintaining the facade.

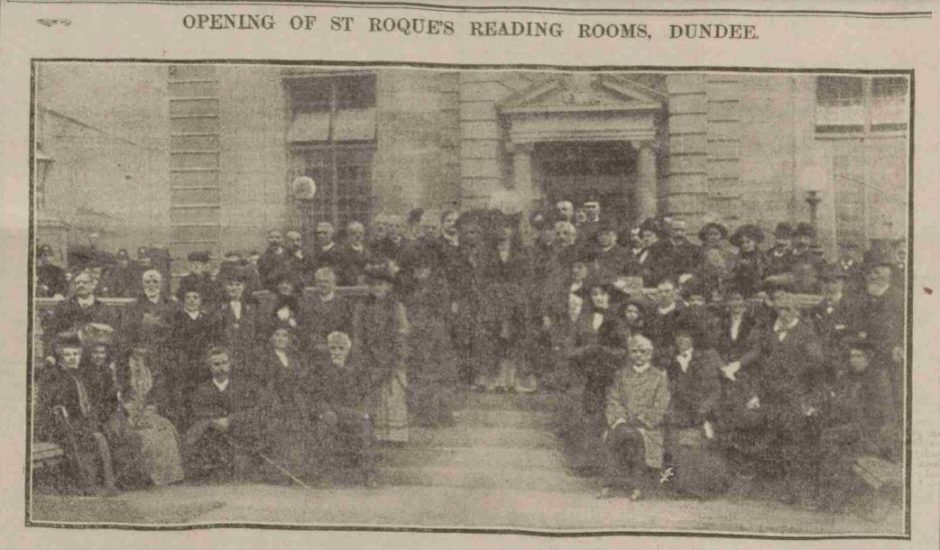

The Reading Rooms: then and now

Risk rating: Moderate

Condition: Fair

When St Roque’s Reading Rooms were unveiled in 1910 as a place for quiet study, nobody could have imagined the library would one day become a noisy music venue.

The Reading Rooms were built on the site of cleared housing in the Blackscroft area as part of the Carnegie library fund to Dundee.

Mrs Urquhart, wife of the lord provost, opened the facility and said: “The chapel of St Roque had disappeared long ago, and in that reading room, the minds of the people would be expanded and cultivated where the bodies of their ancestors were tended.”

She added that in the summer, that grounds would seem like “an Italian landscape”.

Designed by city architect James Thomson and inspired by a French pavilion, the building features elegant arches and carved stonework.

It is set in a triangular garden with railings and a terrace overlooking the Tay.

The B-listed structure was designed for the reading of magazines and newspapers, with a section for use by ladies.

The library itself made the news in 1949 when the lead flashing was stolen from the roof – and later discovered hidden in a pram in a close on Victoria Street.

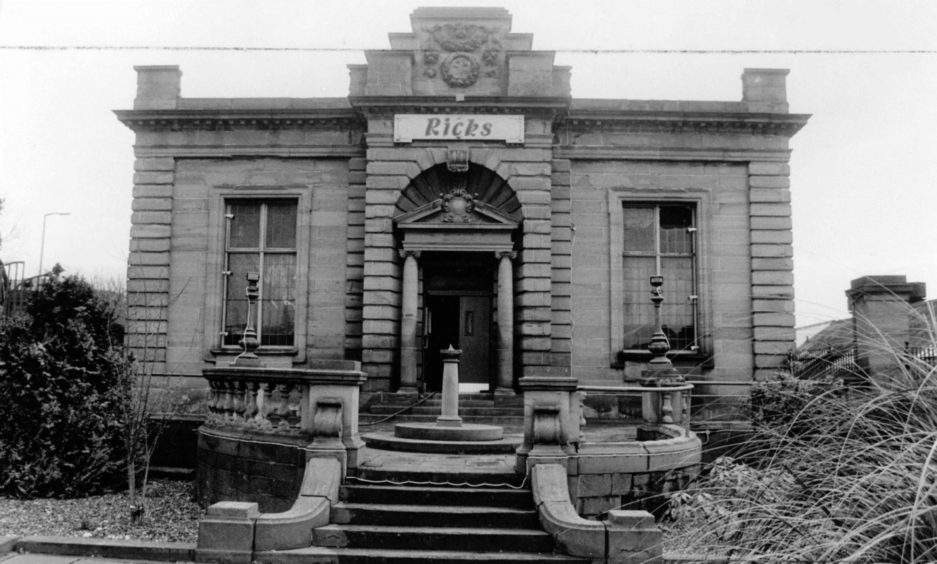

Decades later it became Rick’s Disco before it suffered two major fires and was reinvented as the John O’Groats pub.

The venue was a clubbing destination on and off from the mid-90s, but its latest incarnation as the Reading Rooms Nightclub closed for the final time in 2019.

Following deterioration of its stonework and broken windows, the reading rooms were put back on the buildings at risk register.

But now local business man Derek Souter is bringing life back to the much-loved building with ongoing renovation work and the creation of the city’s biggest beer garden.

The ambitious £800,000 project will see the building brought back into the heart of the community and welcome revellers once more.

A planning statement last year said that the proposals “could ensure long-term commercial sustainability for a listed building which has a rich cultural heritage”, which could ultimately see the building removed from the risk register.

Maryfield Transport Depot: then and now

Risk rating: High

Condition: Poor

It was once a busy transport hub, but the tram rails embedded in the ground in front of the distinctive red brick depot on Forfar Road lead to nowhere.

The handsome building with its red and blue bricks, and vast doors to accommodate trams was opened at the turn of the 20th Century.

Dundee Corporation launched its electric tram route to Maryfield on March 6 1901 and the depot initially houses 12 tramcars before it was extended in 1913 and again in 1920.

It remained in its original use until 1956 when the last trams trundled away to be burnt, replaced with more modern buses.

The imposing sheds stored buses until the late 1980s before the building changed hands a number of times ending up in the ownership of Scottish Water.

The former depot was B-listed in 1993 and added to the Buildings at Risk register in 2002 after part of the structure was damaged by fire.

A section of roof was removed following the blaze and supporting scaffolding remains in place.

Dundee Museum of Transport acquired the site in 2015, in an ambitious scheme to transform it into a world-class heritage destination.

Initial costings put the project at around £4 million and a huge fundraising mission is under way.

Tay Rope Works: then and now

Risk rating: High

Condition: Poor

Behind overgrown shrubbery at 51 Magdalen Yard Road stands the former Tay Rope Works, which manufactured ropes for Dundee’s whaling industry.

The complicated rope production gave the building an unusual shape. It was 558ft long (170m) and broad at the Perth Road end before narrowing to a corridor at the other.

Built around 1837, the once elegant fascade takes inspiration from ancient Greece with carved wreaths and pillars, with the name inscribed above the doorway.

The workshop hit the headlines in September 1937 when a major fire broke out causing £12,300 damage.

It was the most serious blaze the Dundee Fire Brigade dealt with that year, and firefighters needed to use a 4200ft-long (1.3km) hose to extinguish it.

Parts of the building were demolished in 1985 and, despite several attempts to develop the site over the years, it joined the Buildings at Risk register in 2014.

Proposals for housing were first mooted in the 80s and 90s, and the site has been subject to a planning wrangle in recent years.

A bid to demolish the facade was turned down in late 2019 and the developer appealed to the Scottish Government to have it overturned.

The once-busy workshop continues to sit derelict, with only pigeons coming and going.

Forester’s Hall: then and now

Risk rating: Low

Condition: Fair

Designed by architect David Baxter and built in 1901 , Forester’s Hall on Nicoll Street was established for the Ancient Order of Foresters, a type of friendly society.

A handsome building of red and cream sandstone with a striking Art Nouveau frontage, and pyramid slated towers, it became the first home of Dundee Rep Theatre in 1939.

A hive of creativity for decades, the property was vacated in 1963 when a devastating fire took hold.

Although re-roofed, many windows were bricked and boarded up, with its only use in recent years as a solicitor’s office on the ground floor.

Forester’s Hall joined the at-risk register in 2014, and despite conditional permission to change the use of the building to offices, it has remained untouched.

The Art Nouveau carving above the archway is concealed by vegetation, while the once rich, red sandstone is green from algae in places.

The King’s Theatre Trust: then and now

Risk rating: Moderate

Condition: Poor

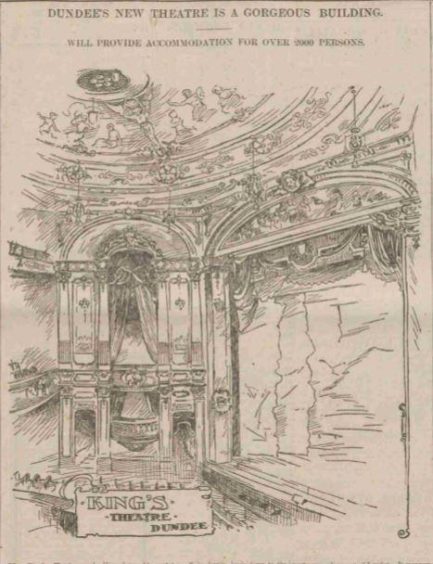

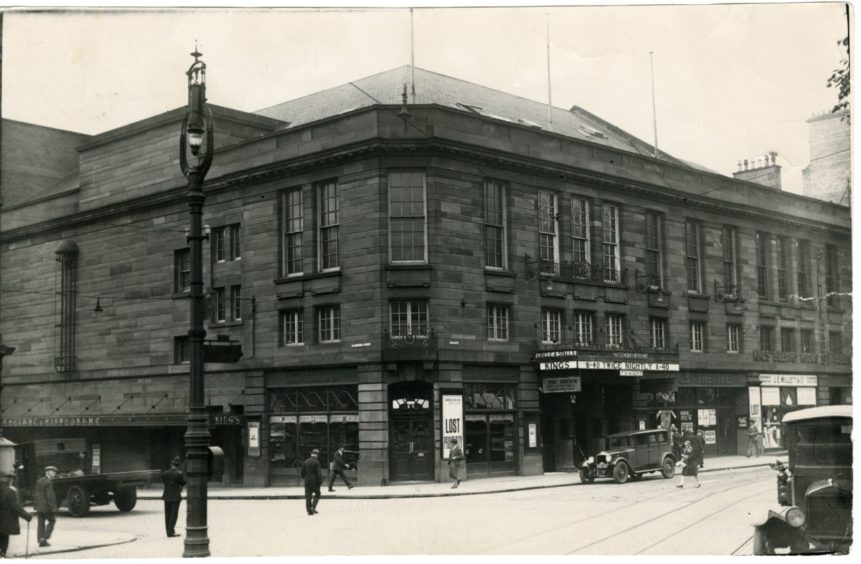

When the King’s Theatre and Hippodrome opened in 1908, it was described as “the latest and greatest” of music hall ventures in Dundee and one of the finest in Great Britain.

And to this day, it is the only surviving theatre in the city capable of hosting touring productions.

The fairly ordinary looking Edwardian sandstone exterior was an “admirable improvement” to city, but hid a 2000-seat auditorium and wealth of opulence inside.

A doorway from the Cowgate opened into a marble hall, while a “lavish and beautiful” staircase lead down to the stalls.

The dome was described as “work of art” and “a fitting crown to as pretty an auditorium as Scotland can show”.

The stage – one of the biggest outside London – was 60ft wide and flanked by private boxes framed in dark marble.

Lady Dunedin officially opened the theatre in March 1909, laying a foundation stone before switching on all the electric lights.

Taking to the stage to make speech, Lady Dunedin said “the inhabitants of Dundee were first and foremost amongst the leaders of light and learning in Scotland who thoroughly appreciated the value of drama”.

But within 20 years the main auditorium was converted into a cinema, renamed the Gaumont in 1950 and the Odeon in 1973.

A makeover in 1955 saw much of the original features removed or covered, and the venue went on to become a bingo hall and nightclubs.

Over the last 20 years, the building has passed through the hands of many owners.

But there have been consistent calls for the B-listed structure to be restored as a theatre.

While the ground floor is in use, the upper floors are vacant and have been affected by water ingress and damp.

The latest incarnation for the building is again as a clubbing venue called Kings, occupied by the club which departed The Reading Rooms in 2019.

The Theatres Trust, along with a King’s friends group, hopes to see the theatre restored to its original purpose, but in the meantime it remains at risk.

Eagle Mills: then and now

Risk rating: Moderate

Condition: Poor

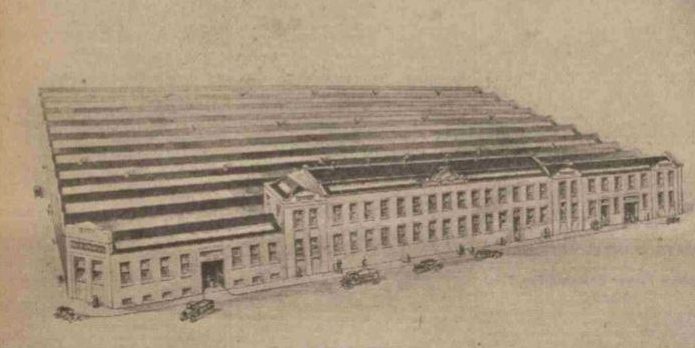

When the new Eagle Mills were unveiled, they were hailed as “the most modern and best equipped jute mills in the world”.

The two-storey mill was originally built in 1864 as the pattern shop for Baxter Brothers Foundry for the manufacture of machinery.

It was hugely extended in the Art Deco style in 1930 and production changed to jute for Low and Bonar Ltd.

The only new mill to be built between the wars, the vast structure was described as “an island bounded by Lyon Street, Brown Constable Street, Dens Road and Victoria Street”.

The state-of-the-art mill had electric machinery, making it quieter than traditional methods.

And the wellbeing of the workers was a big factor in its design.

It was declared that “there is, in fact, no mill anywhere where the lot of the worker can be more ideal”.

This was due to a spacious canteen, a temperature-regulated building, and “modern devices” to get rid of the dust.

The mill made headlines again in 1935 for innovation by allowing women workers to wear trousers on the grounds of safety.

The 150 girls in the spinning department were “immaculately attired in white trouser overalls” and it was reported they looked “really chic”.

Every outfit was made to measure and the mill owners said they considered the move an important safety development, adding “a smarter set of workers you couldn’t find anywhere”.

Since the decline and end of the jute industry, the mill has continued to deteriorate.

The site joined the risk register in 2014 with reports of damp, broken windows and eroding stonework.

More recently it housed a kitchen and bathroom warehouse, but a planning application was approved in 2018 to reinvent the site as flats and business units through a £3.5 million development.

Are there any buildings we’ve missed? Email us at nostalgia@dctmedia.co.uk