Fought over fifteen miles of mud and bringing death to an almost unimaginable 1 million people, the Battle of the Somme was one of the bloodiest conflicts of the First World War.

More than 100,000 British soldiers were sent over the top on the battle’s first day to attack the German lines in what was to have been a grand offensive.

It was a catastrophic failure. German forces huddled in trenches to wait out days of artillery bombardment and then turned heavy machine guns upon the allied forces as they advanced.

A staggering 57,470 young men were mown down on that first day alone and of those 19,240 screamed out their last amidst the muddy shrapnel-filled hell of northern France.

The battle lasted for another five months, in which miles of that mud were taken, then lost and then seized once more.

By its end the allied forces had advanced seven miles, failed to break through the German lines, and treated in the face of the more forcefully advancing winter.

In the wake of the battle the UK was a nation in mourning, the endless death toll having sapped the will of the people and tested their resolve.

The German experience, though huge numbers of soldiers were also lost, was strangely different and will be the subject of a remarkable talk in Dundee by one of the world’s leading experts on German wartime history.

Professor Benjamin Ziemann will deliver Great War Dundee’s Somme commemoration lecture on Saturday July 2.

It will be one of a number of events held in Dundee during July to mark 100 years since the battle began.

In his lecture, he will reveal how the determination of the German soldiers not to be defeated at the Somme resonated back home in Germany.

Professor Ziemann, who is professor of Modern German History at Sheffield University, believes the events in northern France had a “potent significance” in Germany as they encapsulated the “readiness and the willingness” of the nation’s troops to hold out in defensive warfare.

He will explore how, in the German collective memory, the Somme became a symbol of “endurance and collective resolve”.

The professor will be introduced by First World War expert Michael Taylor of the Western Front Association’s Tayside Branch, who is currently completing a postgraduate study of 119th Infantry Brigade during the war.

The free illustrated lecture is entitled “Watch at the Somme – German perceptions of the Battle of the Somme,” and takes place at Dundee University’s Dalhousie Building on July 2, beginning at 6.30pm.

Places can be booked online at sommedundee.eventbrite.co.uk.

The following day, Great War Dundee will host a family day at Verdant Work’s award-winning High Mill to further mark the centenary.

Visitors will be invited to learn more about the Battle of the Somme and watch as a First World War military officer explains technological developments on the battlefield and a nurse teaches how to treat wounded soldiers on the battlefield.

For more information, visit Great War Dundee’s website.

The front line, from the front pages

The Battle of the Somme was the largest Western Front battle of the First World War, beginning on July 1, 1916 and ending 141 days later on November 18.

By the end of the battle, the British Army had suffered 420,000 casualties, with a huge number of Scots losing their lives.

Fifty-one Scottish battalions took part in the campaign, including five battalions of The Black Watch, with the 8th Battalion reduced to just 171 men.

Few photographs of the conflict made their way into British newspapers but some employed the finest war artists of their day to capture the battles.

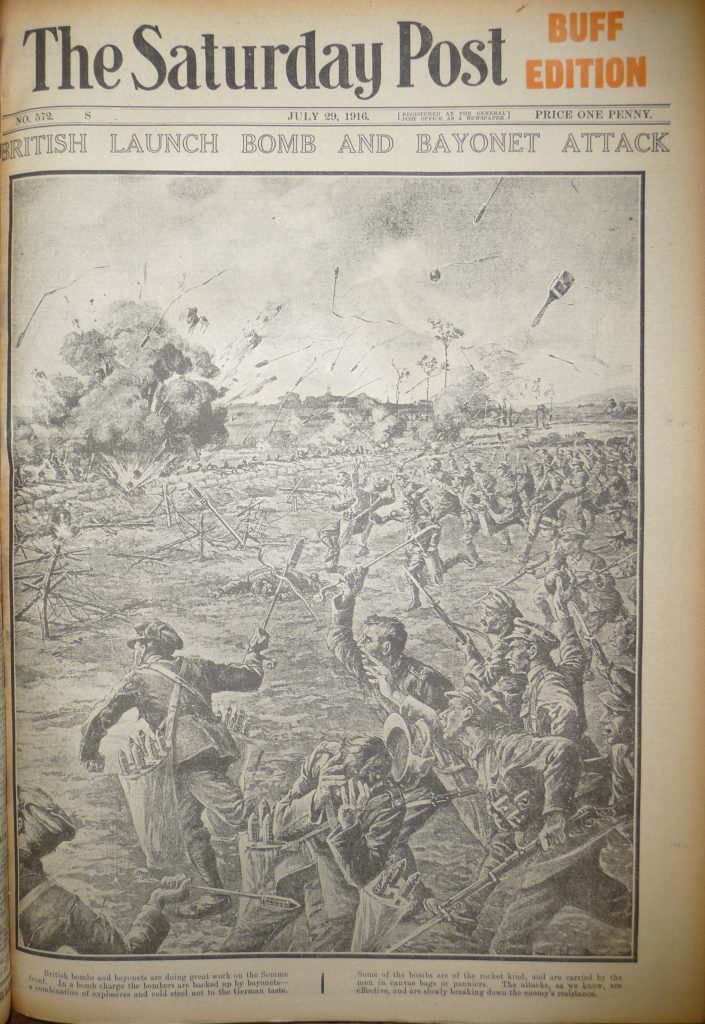

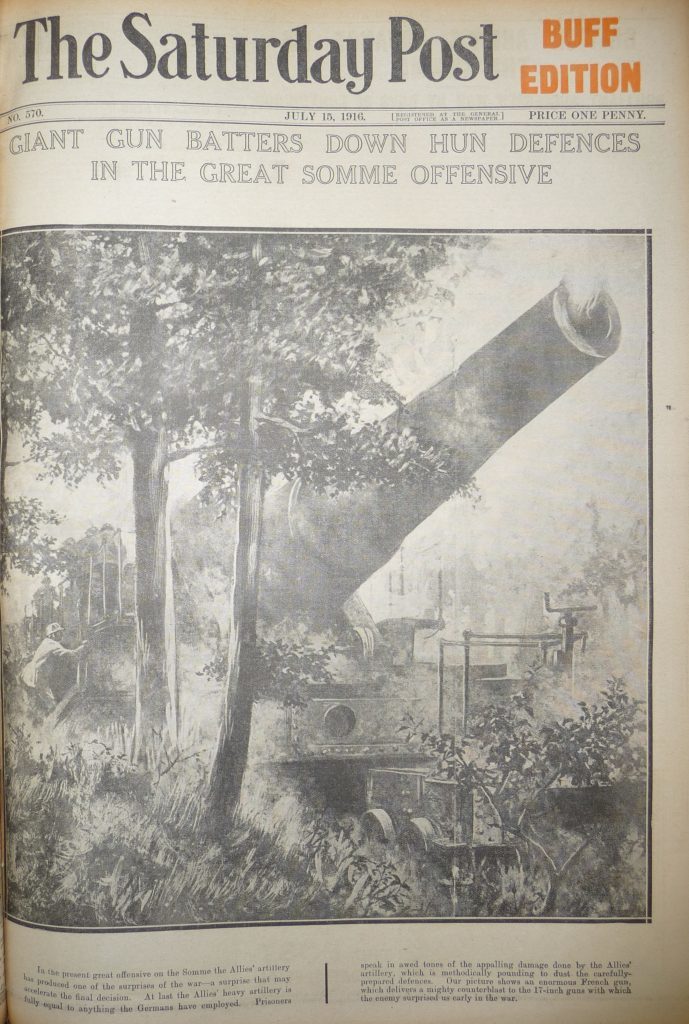

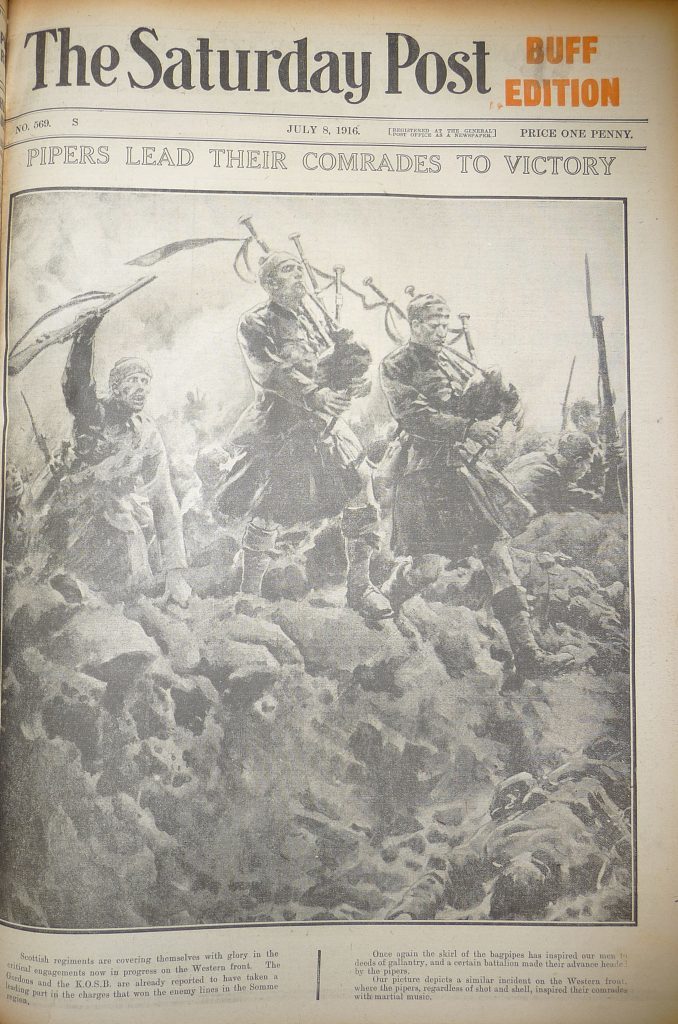

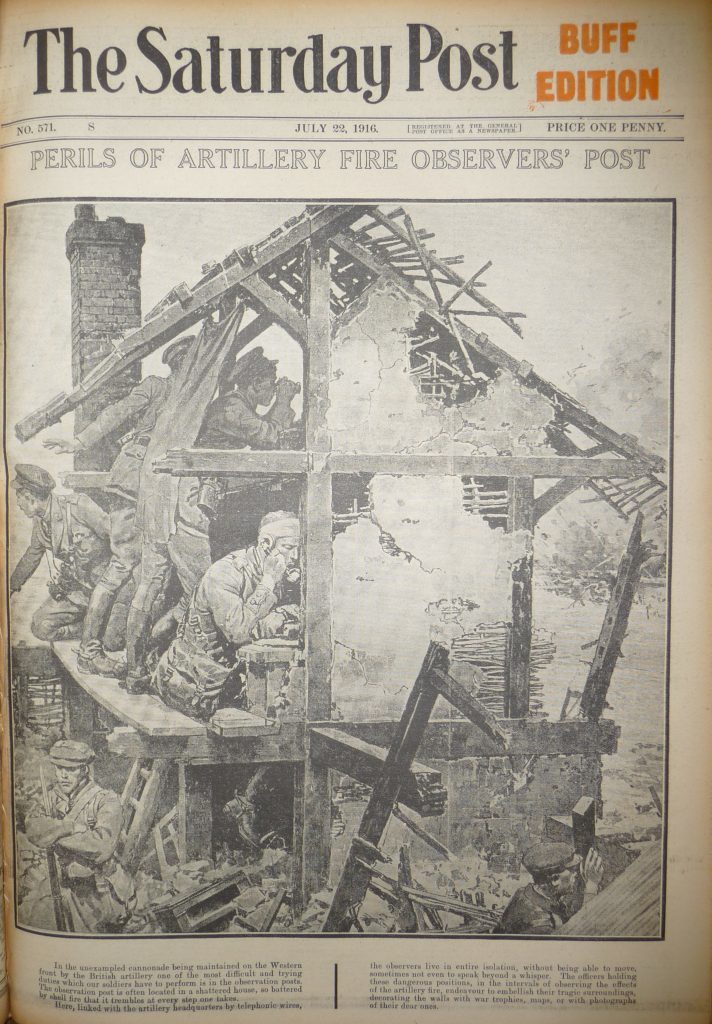

The front pages of The Saturday Post – which predated The Sunday Post – featured numerous striking images as the battle wore on.

They highlighted the heroism of the British Army – though they did not entirely reflect the true horror of the trenches, months under artillery fire and the chill that must have passed through the bones of every man ordered “over the top”.

The Post of July 8, 1916 depicted two gallant pipers leading their comrades to victory, with the accompanying article reporting that Scottish regiments were “covering themselves in glory”.

The skirl of the pipes was said to have “inspired our men to deeds of gallantry”, with the pipers continuing their “martial music” and steady march “regardless of shell or shot”.

A week later, the front page bore the headline “Giant gun batteries down Hun defences in the great Somme offensive” and carried a detailed drawing of an enormous French gun.

It was described as “a mighty counterblast” to the powerful German guns that had so surprised the Allies as the war began.

The Post reported that “many prisoners speak in awed tones of the appalling damage done by the Allies’ artillery, which is methodically pounding to dust the carefully prepared defences”.

In fact, the artillery failed to fully achieve its goal, with the German forces remaining entrenched and unbowed.