As a new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland explores the history of typewriters, Michael Alexander discovers how 19th century Dundee businessman John J Deas was at the forefront of a revolution that changed the world.

When my soon to be at high school daughter insisted she was now old enough to watch the classic 1975 movie Jaws the other week, I was amused to note that during the many times I’ve seen that film, I’d never noticed that when Chief Brody is in his office typing a shark attack coroner’s report, he misspells it as ‘corner’.

It made me think of other classic films with famous typewriter scenes.

These range from the disquieting impact of the ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy’ scene in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining to the symbolism of the typewriter in another of Stephen King’s books Misery – including the black humour moment when broken writer Paul Sheldon simply writes f*ckf*ckf*ckf*ckf*ck…

Older film buffs might recall the classic comedy scene from Who’s Minding the Store (1963) when Jerry Lewis mimes operating a typewriter. The list goes on.

But as my daughter came to terms with the powerful impact of John Williams’ famous Jaws theme and the ability of two notes to stir emotions around a rubbery-looking mechanised shark, it hit home that in this digital, mobile phone-dominated, touch-screen world, she had no reason to know what a typewriter was.

Typewriters from a by-gone era

For readers of a certain age, the clickety-clack sound of typewriters was once synonymous with office life – including newsrooms – and many homes would have one too.

The development of word processors, personal computers and laptops since the 1980s all but consigned typewriters to the past – although for nostalgia nerds or sheer novelty, several apps have been developed in recent years that simulate the typewriter keyboard sound, including the distinctive ‘ding’ at the end of each line.

Now, a new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland, starting on Saturday July 24, examines the social and technological impact of typewriters over more than 100 years, from early prototypes to stylish mid-century models, which are still in use today.

The Typewriter Revolution charts the development of these iconic machines and explores their role in society, the arts and popular culture through the personal stories of those who designed, made and used them.

The Typewriter Revolution draws on National Museums Scotland’s significant typewriter collection, with highlights including an 1876 Sholes & Glidden typewriter which was the first to have a QWERTY keyboard, a 1950s electric machine used by Whisky Galore author Sir Compton Mackenzie, and the 1970s design icon, the Olivetti Valentine.

Broad history

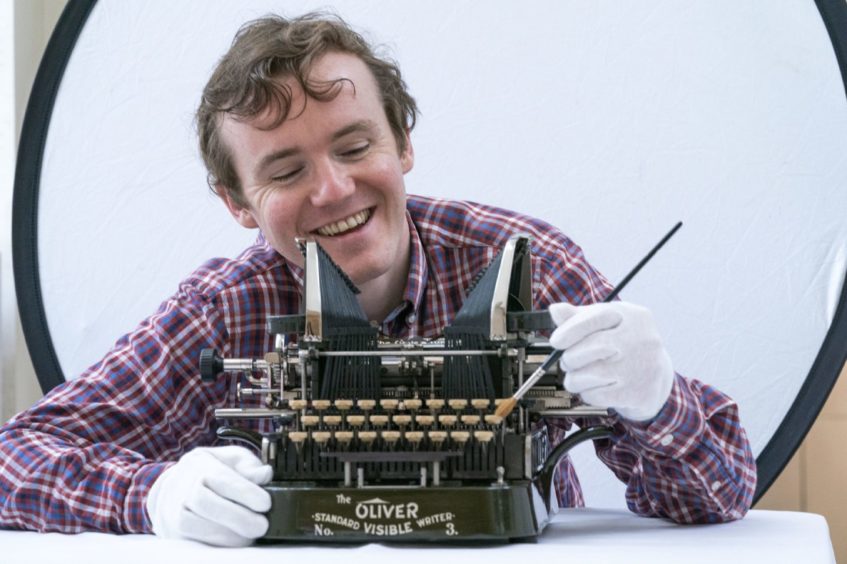

James Inglis, a PhD student at St Andrews University, has been working in collaboration with National Museums Scotland to set up the exhibition.

Speaking to The Courier about its inspiration, he says: “It’s basically a broad history of the typewriter from the kind of early writing machines of the early 19th century – experimental machines – and going through to the development of typewriters and 1980s when you get word processing electronic typewriters.

“A lot of the story of the typewriter is an American story, but I’ve been able to come up with stories about people who were first involved in selling typewriters and using typewriters basically in the principal four cities of Scotland – Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee and Aberdeen.

“A lot of my research has fed into the exhibition, and broadly speaking it’s kind of half social history, telling the stories of some of those involved.”

Role of Dundee man John J Deas

Typewriters were first shipped across the Atlantic by American firm E. Remington & Sons in the 1870s.

They were luxury devices which cost the equivalent of half the average annual salary.

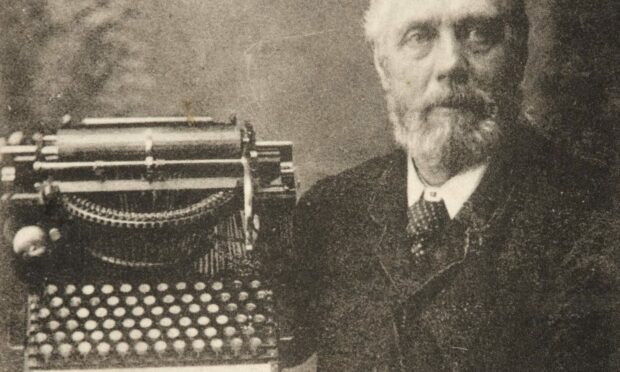

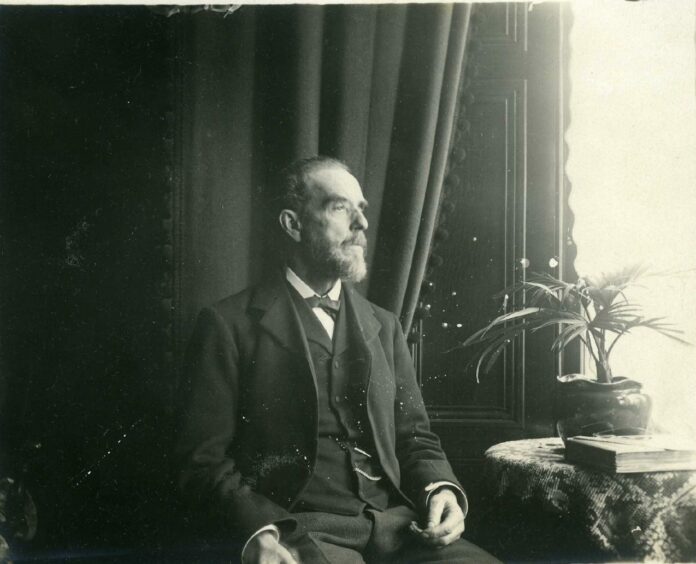

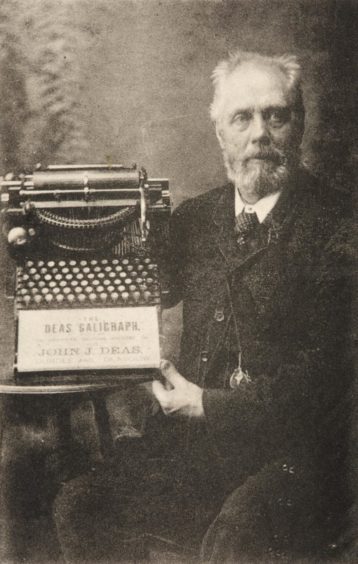

A particularly interesting Dundee character linked to the exhibition is John J. Deas.

Born in Dundee in 1828, he pioneered the sale of typewriters in Scotland and was one of the key figures who popularized typewriters in Scotland during the late 1800s.

The son of a Dundee flax dresser, John was very prominent in the city, starting off in the textile trade and buying and selling fabrics from the 1850s.

Then in the 1870s he got involved selling imported sewing machines – the really big technology of the post American civil war period.

He built on his American business connections and through these links came across the typewriter.

Adverts for his business in Dundee and Aberdeen claimed the typewriter would “do for the ink-bottle and the pen, what the sewing machine has done for the needle”.

“Deas was very passionate about American innovations generally,” says James.

“He saw this as a new opportunity to sell. He thought typewriters would sell well.

“But not a lot of people at that time necessarily saw the value in typewriters. He had to go out and persuade people why a typewriter would be a good thing to buy.

“They pitched them to different groups of people like journalists, authors and people who work in offices.

“But that was difficult because they were really really expensive as well.

“The first typewriter made by Remington is about £25 which is over half a year’s salary for the average person. He became passionate about trying to sell these things from the late 1870s.”

Growing Dundee business

As an early amateur photographer with a passion for new technologies, Deas established the Deas Royal Machine Depot at 137-139 Nethergate and had other shops in Perth Road, Magdalen Yard Road and 1 Mid Street.

Deas’ first customer – to whom he sold a Sholes & Glidden typewriter – was Baroness Burdett-Coutts (1814-1906), a philanthropist and one of the wealthiest women in the UK during the 19th century.

She first saw the Sholes & Glidden at a private demonstration held at Deas’ Dundee home.

Adverts published by Deas in early 1877 quote Burdett-Coutts as saying, “The Type Writing Machine will be a great boon to your Cowgate Merchants”.

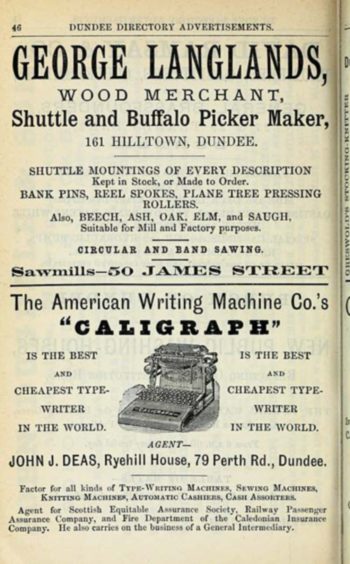

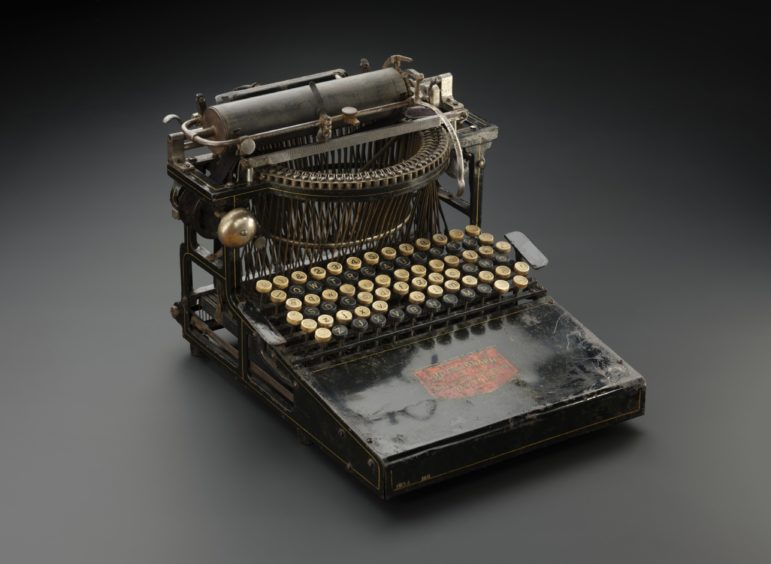

His business took off from there, and he later took delivery, from the US, of what was reputedly the first Caligraph to arrive in Europe.

Impressed by this new writing machine, he had Caligraphs imported on steamships.

The first few Caligraphs arrived in Scotland in 1883, and by the following year Deas was importing around 12 cases per month.

The breakthrough for John Deas came in 1890 when he had his own specially adapted “Deas Caligraph” typewriters built at a Coventry factory.

In 1891, he announced to readers of The Courier: “To my Friends in Dundee, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen. I have just returned from Coventry, where I get the “DEAS CALIGRAPH,” Built to my Special Instructions… I can candidly – from an experience of nearly 16 years – Recommend the “DEAS” as being by far and away the Best Typewriting Machine on the Market.”

Love of rowing on Tay

During his research, James discovered other details about Deas’ life. An archived article from the Dundee Evening Telegraph revealed that every morning at 6am, he would go up and down the Tay on a rowing boat with fellow Dundee shopkeepers.

He was also the first person to open a Christmas fancy good show – ‘the basement of his shop was converted into a Father Christmas snowy cave all aglow with lights and a great attraction it proved’, another Evening Telegraph article recalls.

Of his three daughters, Isabella became a successful businesswoman in her own right with Dundee drapers DM Brown.

It was as a pioneering businessman, however, that he was best remembered.

On his death in 1903, a friend said of him: “He foresaw the coming of the typewriter, and at a very early stage in the history of the machine he acted as its herald in this and other quarters. There are many Dundonians scattered all over the world who will learn with regret of the death of their old friend John J Deas.”

Time of workplace change

The expansion of the typewriter often ran in parallel to changes in business administration and more women taking up office jobs.

However, an important point raised in James’ research is the number of women who set up their own typewriting office businesses, which created employment.

The final decade of the 19th century saw a huge boom in the demand for typewriters as organisations began to realise their value, and by 1900 they had revolutionised the world of communications, transforming office work and opening up new employment opportunities, especially for women.

They inspired novelists and artists, with Mark Twain among the first to use what he called a “new-fangled writing machine”.

Henry James liked the loud clacking of a Remington typewriter and found that his inspiration dried up when he upgraded to a quieter model.

Jack Kerouac typed out On The Road on a 36 metre-long manuscript because he wanted to write continuously.

In the late 1940s, the Italian firm Olivetti opened a factory in the east end of Glasgow, later producing stylish models such as the Lexikon 80, and the portable Lettera 22 which were seen as the cutting-edge of design.

Typewriter technology advanced to include electric models from the 1920s before the rise in computers saw them gradually phased out of offices.

However, the unique experience of writing on a typewriter and the enduring beauty of their design mean there is still a demand for the machines.

How did James Inglis get involved?

As a University of Westminster history graduate, Worcester-raised James Inglis, 27, became interested in the history of technology while studying for a Masters at Royal Holloway. He did a project with Tower Bridge interviewing people that worked there.

He didn’t know much about typewriters at that time, he admits, but when he saw an advert for the St Andrews University research project, in collaboration with the National Museum of Scotland, he thought it sounded “really interesting” and secured the post.

“The exhibition is really driven by the objects,” he adds.

“We want to see really nice typewriters on display and have really nice stories around that, because the first one we’ve got is an early machine by Peter Hoods who was a watchmaker based in Kirriemuir in Angus in the 1850s.

“In his workshop he made this writing machine and again, it doesn’t look anything like a typewriter, but it is a writing machine.

“That’s the first machine we’ve got in the exhibition to start the story.

“And then it goes through the history. We’ve got a Remington model from the 1870s, we’ve got the Caligraph one I was saying of the type John Deas would have sold.

“Then we’ve got a lot of these machines from the 1880s/1890s which really will hopefully show the visitor they are really diverse designs.

“Then we go through to portable typewriters. We look at the Olivetti factory in Glasgow.

“In Scotland after the Second World War there were three companies based here that made typewriters – Olivetti was probably the most successful in Glasgow; Remington Rand – who (former Manchester United manager) Alex Ferguson worked for briefly – and IBM, Greenock who briefly made typewriters in the 1950s in Scotland.

“So, yeah, it’s driven by the machines and we’ve got these social history stories around it. We hope it’ll be of interest to all.”

National Museums Scotland has been awarded the UK-wide, industry standard “We’re Good To Go” accreditation. This means the museums have followed Government and public health guidelines, have carried out Covid-19 risk assessments and have the appropriate processes in place.

The Typewriter Revolution runs at the National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, from Saturday July 24 until Sunday April 17, 2022. Admission is free with pre-booked museum entry.