“You’ve never had it so bad” was the catchphrase of the time during possibly the darkest period in Scotland’s recent history.

Petrol prices rocketed, coal was like gold dust and industrial unrest was rife and the introduction of a three-day working week meant the lights could go out at any time.

Blackouts, meals by candlelight, frost-encrusted homes and empty shelves was part of daily life across Tayside and Fife in the winters of 1972 and 1973.

Fifty years on, it’s hardly surprising memories of that bleak period still send shivers down spines with the prospect of a new wave of power outages this winter.

The head of the National Grid warned households that blackouts may be imposed on “really, really cold” winter weekdays if European countries cut gas exports to Britain.

Blackouts of 1972 were just a warm up

Much of this will seem familiar to those who lived through the 1970s.

Unlike today, most of Britain’s electricity came from coal, and so crisis struck when miners voted to strike over wages for six weeks between January and February 1972.

Miners picketed power stations in an effort to restrict coal supply, leading to mass blackouts around the country and businesses being forced to close.

Back then it was a bit random when you would be plunged into the gloom. Your lights would flicker a bit, dull down to brown then just go off.

Edward Heath’s Tory government eventually capitulated and gave the miners a pay rise but the blackouts of 1972 were just a warm up for what followed in 1973.

Interest and inflation rates were in double figures and rising, the national debt exceeded £3 billion and union militancy was on the increase.

The war between the Arabs and the Israelis which had started in October 1973 compounded the problems.

Oil prices rocketed, demand for coal increased and the miners, bitterly unhappy with their weekly pay packets, sensed an advantage and pressed their wage demands further.

When the government’s best offer fell well short of the union’s demands, miners introduced an overtime ban.

The result was a crippling 40% drop in coal supply to power stations.

Within weeks the country was almost at a standstill and the government called a state of emergency from midnight on Tuesday, November 13, 1973.

The next week they brought in a recommended speed limit of 50mph to conserve fuel.

Petrol coupons were issued from Thursday, November 29, because there was a petrol embargo by the Arab states and garages had very restricted supplies.

Some Dundee garages started rationing petrol following the announcement of a 10% cut in their supplies with several imposing a four-gallon limit for customers.

By the beginning of December nearly every garage in the city was closed as a result of smaller fuel deliveries with motorists having to travel around to get supplies.

One of the few garages open, St Roques, was giving only a gallon per customer.

The local spokesman for the AA said at the time: “There were a lot of queries over the weekend from motorists wanting to know where they could get petrol.

“Our patrolmen were having difficulties in getting petrol themselves.

“They were only able to get one gallon each from St Roques. By the evening they were running low on fuel.

“There were one or two calls yesterday from stranded motorists outside the city.

“Where possible we took petrol out to them but obviously we will not be able to do this much longer and it will stop altogether if petrol rationing comes in.”

Staggered working hours, tailored to suit the individual requirements of employees, was suggested as a means of coping with extra demand for buses in Dundee.

Transport manager William Russell said: “If everyone wants to travel within a period of half an hour at the peak and we are going to have extra passengers thrown at us because people have to forsake their cars, then there is no doubt there will be queuing.

“But if people are prepared to adjust their travel habits away from peak periods, there will be seats for all.”

Dundee won the 1973 League Cup

Football was not high on the priorities for the available power and the use of floodlights was banned, eventually extending to power generated by private generators.

All matches had to be played in daylight so kick-off times were brought forward including the Dundee versus Celtic League Cup final at Hampden on December 15.

The game was scheduled to kick off at 1.30pm.

Gordon Wallace wrote his name into Dundee folklore with the winning goal.

Alas, there was no open-top bus display on their return to the city, with the team heading to the bar at the Angus Hotel to celebrate with clubmates and family.

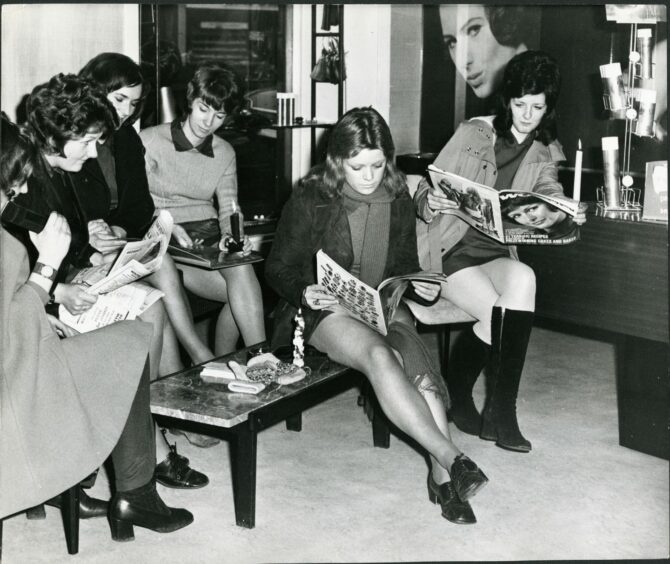

Some pubs though were left dry except for bottled beer, patrons forced to drink by candlelight, whilst shop workers around the country used head torches to keep trading.

The Courier and Evening Telegraph carried a timetable of which shops were open and for how long alongside which areas would lose power and when, so you could prepare.

The week before Christmas Littlewoods and M&S in Dundee remained open all week although only their food section was lit by electric light every day while the textile sections would rely on daylight but close to customers when the light faded.

Street lights across Tayside and Fife were also being switched off before Santa arrived which involved the reduction by half of all high-wattage lamps in quieter streets.

The remainder were shut down at midnight.

The power cuts saw a shortage of candles and stores were selling out of paraffin lamps although some butchers decided to make candles out of string and animal fat.

After his plea to the nation to voluntarily reduce energy use fell on deaf ears, Heath announced that from January 1 1974, the country would only be allowed to work three days a week.

Declaring a state of emergency, he ordered power cuts and demanded TV screens be blacked out at 10.30pm in the hope it would encourage people to go to bed early.

Services deemed “essential” were exempt from the action. These included hospitals and supermarkets, along with newspaper printing presses, which were seen as an important mechanism for ensuring the public remained informed of events.

Then, in mid-January, with uncollected rubbish piling up on the streets and public transport effectively crippled, the official tone suddenly became more anxious.

During a radio interview, Minister for Energy Patrick Jenkin revealed it could become illegal to light and heat more than one room.

He even urged people to clean their teeth in the dark!

Heath’s gamble didn’t pay off

Amid the crisis, Heath called a snap election for February 28 under the slogan: “Who Governs Britain?”

His gamble was that the public would side with his government rather than voting to maintain the then immense power of trade unions.

Addressing the country on television, he said: “Do you want parliament and the elected government to continue to fight strenuously against inflation?

“Or do you want them to abandon the struggle against rising prices under pressure from one particularly powerful group of workers.

“This time of strife has got to stop. Only you can stop it.”

Labour won by four seats.

Heath attempted to strike a power-sharing deal with the Liberals.

When that failed, he resigned.

Within a day of Harold Wilson returning for his second term as Prime Minister he’d persuaded the miners to go back to work by sanctioning a 35% pay rise.

The three-day week was abolished by March and things returned to normality although those first three months of 1974 did provide some unusual benefits.

There was a baby boom.

People couldn’t watch TV at night so they did other things instead.

Might we see similar scenes in 2023?