As a thought-provoking exhibition about death and dying closes at Dundee Botanic Garden, Michael Alexander speaks to some of those encouraging conversations around the often tricky subject of grief as concerns are raised about funeral poverty.

Government figures show that as of the end of October more than 207,000 people in the UK had Covid-19 on their death certificate while around 195,000 had died within 28 days of a positive Covid test.

The death rate in the UK stands at around 600,000 per year for all causes.

But beneath the statistics, what’s the lasting human impact for those who suffered bereavement and loss during the global pandemic?

What’s the legacy for family and friends who were unable to spend time with loved ones when they died during lockdown?

What are the consequences for people who were cut off from support networks and then had the upset of funeral attendances being extremely limited?

Encouraging conversation

The “massive” impact of Covid-19 on peoples’ ability to process death and grief is of huge interest to Marie Curie community engagement officer Helen MacGregor, who is on the steering group for Say Something Dundee.

They recently worked in partnership with University of Dundee Botanic Garden to bring an exhibition about death, dying and grief to the city.

One of the recurring themes she’s become aware of is how death touched people during the pandemic.

That ranged from reaction to someone they knew passing away or a collective sense of anxiety about the state of the world.

However, she also wonders if the mass outpouring of grief for the Queen in September was linked to pent-up collective grief for everything that’s happened since March 2020.

Impact on grieving process?

“During Covid, a lot of the things that came out of conversation sessions was a real sense of holding and waiting,” she said.

“For example during Covid, people would be having a real back to the absolute minimum funeral with the intention of then having a kind of more wake element at a later date.

“But that has meant that people have been in that waiting phase for extended periods of time.

“I think the connections you have with people are so important during that period when you are able to touch and console and listen.

“It’s so much easier to listen when you are face to face rather than when you are on a video call.

“I think it’s been a huge thing for the whole population whether you’ve lost somebody close to you or whether you’ve just kind of been witness to the environment that we’ve lived in.

“I think it’s going to take many years for people to recover.

“But another thing I was very interested in was the death of the Queen.

“You almost felt that funeral was the communities around the UK getting the chance to have the funerals that they maybe didn’t get to have during Covid.

“I think that was a much bigger representation. Maybe not. But it feels to me like it was maybe quite different than it would have been had Covid not happened before hand.”

Aims of Dundee exhibition

As part of this year’s To Absent Friends festival Say Something Dundee invited people to enjoy the late autumn surroundings of the University of Dundee Botanic Garden while experiencing the thought-provoking exhibition ‘It Takes a Village’ by award-winning Glasgow photographer Colin Gray.

The exhibition was based on the old African proverb –‘It takes a village to raise a child – meaning, children need the input and support of their whole community to grow into well-rounded adults.

But it also posed the question doesn’t it also ‘take a village’ to support someone who is dying?

The Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care worked with Colin to produce a powerful and challenging series of portraits and personal stories.

Through a series of photographs and personal statements, it explored the idea that as people’s health deteriorates, care and support comes in many guises.

For example, Stefanie, a care assistant in a care home for people with dementia said: “You have to learn to take grief in your stride almost.

“I’d never seen a dead person before.

“Their little room in the care home is empty and somebody else will come along and fill it.

“It’s ok to cry. But you’re still at work. You still have responsibility for all the other residents, who still need you, relying on you.”

Euan, a GP, said: “I firmly believe that it is often the ‘little things’ that matter most.

“And I think that sometimes they get overlooked because they’re seen as ‘little’…

“There was a man who died of motor neurone disease a couple of years ago.

“I saw him weekly, and then daily, for 18 months.

“He was paralysed, there was no family local to him, and he was a smoker.

“When I’d get to his house, I’d light a cigarette and hold it in his mouth. Then I’d give him another one before I went away.

“Lighting those cigarettes was probably as important as many of the medical things I did for him.”

In another statement, taxi driver Tony said: “She must have been in her 30s, she was very tearful, she’d been visiting her dad at the hospital.

“She said that he only had another couple of days maybe.

“She just had to go home and get a shower, she’d be coming back again.

“Sometimes you get the nice feeling that you’ve helped somebody a little, just by providing an ear.

“Sometimes people are comforted that real life is going on, the wheels of the taxis are turning and the world goes on, and everything isn’t coming to an end.”

What were aims of festival?

The To Absent Friends festival, which took place across Scotland from November 1 to 7, acknowledged the fact that people who have died remain a part of our lives – their stories are our stories.

Yet many Scottish traditions relating to the expression of loss and remembrance have faded over time.

To Absent Friends gave people an excuse to remember, to tell stories, to celebrate and to reminisce about people they love who have passed on.

Meanwhile, Say Something Dundee, which helped put on the Botanics exhibition, is a partnership project between Funeral Link, Dundee Volunteer and Voluntary Action, University of Dundee and Marie Curie.

They were awarded support from Good Life, Good Death, Good Grief to come together as part of The Truacanta Project looking to create compassionate communities.

Helen explained that their aim is to make conversations around death, dying, loss and care easier to initiate through campaigns, workshops and discussions.

By choosing to be open about it they are all part of a movement that’s changing the conversation and ensuring that no one is made to feel isolated or alone for having a struggle with pain, bereavement, grief and loss.

Bulb planting

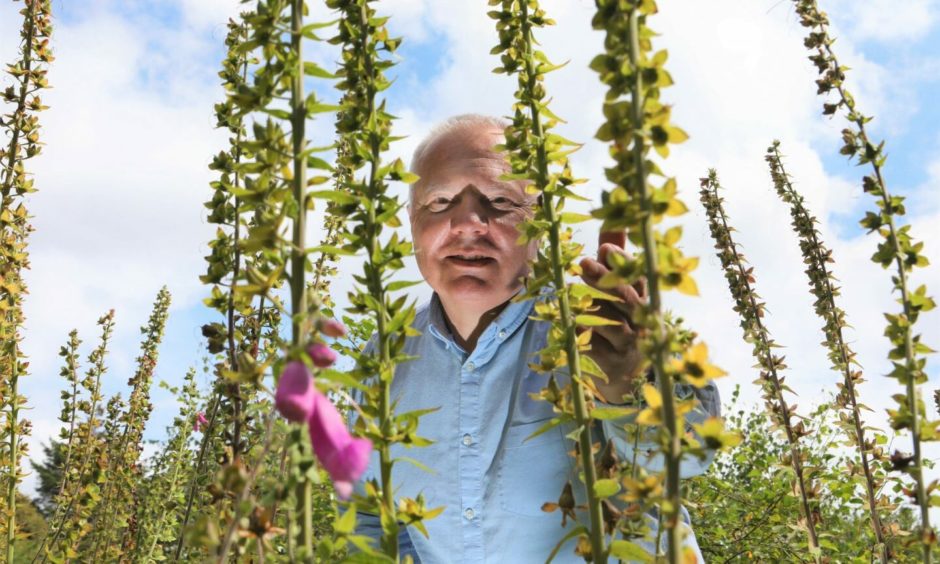

Speaking as commemorative bulb planting took place to bring the Dundee exhibition to a close, Helen says it’s interesting because, while people might often feel reluctant to broach the subject of death, actually people do often want to talk about it if and when the conversation comes up and the time is right.

“Speaking very personally I think a lot of that’s about not knowing where the other person’s at,” she said.

“Say, for example, an ageing parent wants to discuss their plans in planning ahead mode – they want to have a chat to their offspring about it and the offspring rebounds back and says ‘oh no we don’t want to talk about that’ – I think that’s a very common thing that happens.

“And actually it’s not necessarily that they don’t want to have the conversation.

“It’s that they don’t want the other person to be thinking ‘oh you are going to die soon’.

“So it’s a kind of protective thing I think.

“But I do think when the conversations happen, it creates a kind of a position where people feel more in control and are able to make plans and be open and it does definitely have a positive impact if you feel like you’ve been able to share your thoughts and feelings on the subject.”

Opportunity to remember

Kevin Frediani, curator of Dundee Botanic Garden, said the exhibition – and the gardens themselves – offered people the opportunity to take some time to remember their own absent friends.

An already poignant place is the SiMBA Tree of Tranquility which was installed in the gardens in June 2019.

The tree bears individual leaves which have been engraved with a personal message, each one representing a forever loved and missed baby.

It led Kevin to think further about the space in front of it being more empathetic to supporting good life, good grief and good death.

It coincided with masters student Lorena Weepers – designer and originator of the Good Grief Garden – coming to see him prior to lockdown.

She’d lost her uncle and was exploring through her own art therapy work the concept of memorial gardens.

It’s a memorial garden concept they’ve been working on since.

Notes of remembrance can be left by family members and they are collected and composted once a month.

The compost is then dug back in with the individual emotions coming together to become part of something much bigger than themselves.

Funeral poverty concerns

Meanwhile, Dundee-based charity Funeral Link is concerned about the cost of living crisis and the growing impact on funeral poverty.

Their service manager Linda Sterry said: “We are deeply concerned about the current cost of living crisis and what this means for our local people faced with a bereavement this winter and beyond.

“We understand the challenges faced when planning a funeral on a low income with little, or no, savings and not knowing where to start.

“If you or someone you know is in this situation, then please call Funeral Link on 01382 458800 and we will do our best to support you to save money on funeral costs.”

Funeral Link are currently recruiting two part-time roles one of which is a Say Something Dundee development worker to take this Compassionate Communities work forward in 2023. More details can be found on their Facebook page.

Conversation