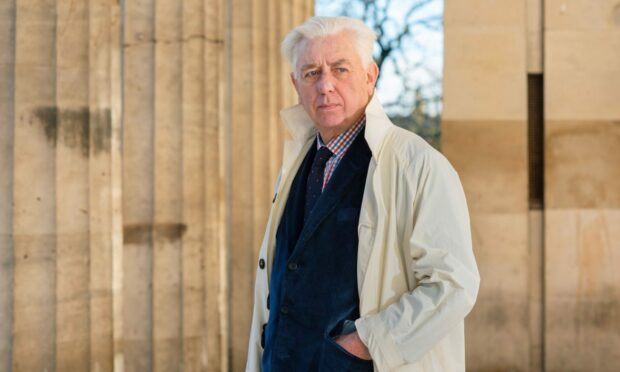

With all three honorary positions at the Royal Scottish Academy now held by Dundee-artists, Michael Alexander speaks to newly elected RSA president Professor Gareth Fisher PRSA about the role art has played in the regeneration of the city.

Dundee was a very different place when the recently elected president of the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) Professor Gareth Fisher PRSA first visited in the late-1970s.

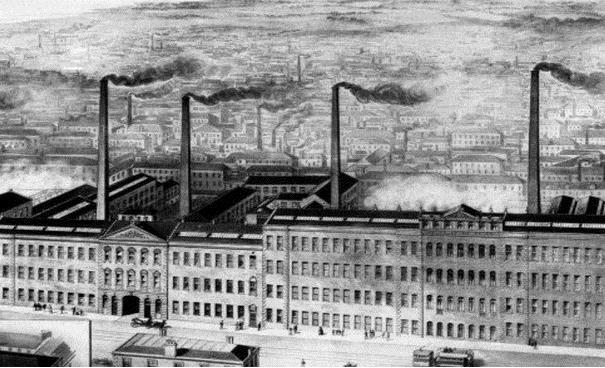

Invited to lecture part-time at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, and eventually securing a full-time contract before moving to Dundee in the mid-1980s, he was struck by the city’s mills – particularly in the Blackness area – and vividly recalls the thick smell of jute hanging in the air.

‘Town was changing rapidly’

He was also struck, however, by the “potential” that the city had and, as an artist, he found this incredibly exciting.

“Without being disrespectful, Dundee felt like a bit of a frontier town in those days,” he says.

“It seemed to me to be a town that was changing rapidly and had come to the end of its industrial past and was looking for a new future.

“In a way as an artist, I found that quite interesting because having come from Edinburgh which at that point in time had more of a cultural base, coming to Dundee and ultimately coming to live here – I sensed there was a lot of opportunity.

“But it was also pretty raw. We are talking about pubs not having ladies’ toilets. Some quite rudimentary things.

“And the street I first lived in when I came to Dundee – Springfield off the Perth Road – still had gas lights on the street. That was in the mid-’80s.”

College had ‘solid reputation’

Professor Fisher said Duncan of Jordanstone had a “solid reputation” when he arrived as a young lecturer.

Giant figures like Alberto Morrocco and Dave McClure were very prominent and running the art school.

The person who had just retired as head of sculpture was Scott Sutherland – the man who created the Commando memorial at Spean Bridge, and also created the Black Watch Memorial on the outskirts of Dundee.

Yet alongside these major reputations was a feeling that the art college had to become more modern in its outlook.

It was with this in mind that Professor Fisher was employed as part of the college’s mission to introduce more contemporary approaches to education. Later, the college merged with Dundee University.

Less traditional approach

“There was a small group of us – myself and Will Maclean who lived across the water – we started teaching drawing classes and started approaching the education of young artists in a slightly different, less traditional way,” he recalls.

“There was an art historian at the time called Timothy Neat – he worked a lot with the travelling people around Blairgowrie and did a lot of films about the Scottish travelling people.

“He introduced a lot of new education approaches to contemporary art.

“My mission along with three other people was to move the college away from what you might call traditional figuration towards a broader spectrum of what art could be for young people.”

Born to be a creative

Brought up in Keswick, Fisher had gained an early insight into how art could inspire young peoples’ lives.

His silversmith father worked in a Ruskin workshop dedicated to training young people to work in craft.

When young Gareth started thinking about going to art school, he applied to Edinburgh because his family had connections with the city.

Getting in on the second attempt in 1969, he studied at Edinburgh College of Art for seven years – five years as an undergraduate and two years post-graduate – where he specialised in sculpture.

He also went to New York on a “very enlightening” travelling scholarship.

It was Dundee, however, that was to have perhaps the greatest influence on his life.

The city had a huge influence on his own art.

Just two or three years after moving to Dundee where he had a studio in the living room of his Springfield home, he was one of only a handful of Scottish artists whose work was selected for the Biennial British Art Show.

Influence of Dundee environment

Looking back, he thinks that was entirely due to the fact he was living and working in Dundee and was making work that was about Dundee and its environment.

Around that time, he remembers a photography lecturer called Joe McKenzie whose beautiful photographs can be found to this day in the McManus.

McKenzie would go out every lunchtime and take photographs of the Old Hawkhill, its tenements and ultimately their demolition.

Not long after coming to Dundee, Fisher also got involved with a group of local artists involved in what was then called the Blackness Public Arts Programme – later becoming the Dundee Public Arts Programme.

At a time when the then Dundee District Council and the Scottish Development Agency were looking at ways to rejuvenate Dundee, they worked with them to commission artists to make artworks around the city.

They also got involved in the project to bring RRS Discovery back to Dundee.

From some of those early days of workings came the whole idea of an arts centre like DCA.

But at its heart was an exploration of the power art has to help rejuvenate an urban environment.

“The Blackness and Dundee public arts programme were set up under the SDA to specifically look at how the arts and creativity can change a city,” he says.

“I was working closely with a person called Bob McGilvray.

“We had regular meetings with Dundee District Council at the time just persuading them really that whenever new buildings were going up, whenever areas were being developed, there should be some artistic input.

“One of the reasons we were doing that was not just for the actual infrastructure.

“It was also to try and give opportunities for artists and make them stay in Dundee after graduating.

“Everyone who graduated from the college of art in the ‘80s – they more or less left quite quickly because there was very little for them there.

“The difference between then and now is immense.”

International exhibitions

Fisher has exhibited extensively both nationally and internationally during his career, including major solo exhibitions at Mercer Union, Toronto; Abbot Hall, Kendal and Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh.

Additionally, he was included in significant group shows in Artists Space, New York in 1979, the British Art Show in 1986 and ‘Scatter’ at CCA Glasgow in 1989.

In the 1970s, he sat on the board of the innovative New 57 Gallery, ultimately becoming its chairman in 1978.

The gallery curated exhibitions including the Scottish debuts of important artists such as Joseph Kosuth, Kurt Schwitters, Jock McFadyen, Marcel Broodthaers and John Stezaker.

At Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, Dundee, he held the position of head of undergraduate studies in fine art, ultimately becoming a professor of sculpture.

During his tenure, Fisher managed the multi-million-pound regeneration of the art college buildings.

Royal Scottish Academy roles

However, he’s also been heavily involved in the work of the Royal Scottish Academy.

In 2003, he was elected an associate. Becoming a full academician in 2006, he has played an important role in various RSA committees and served as treasurer from 2013 to 2016.

Having retired from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design six years ago, he retains a studio in Dundee and still lives in the city.

It was announced in November that Professor Fisher now takes up the academy’s highest honorary position as it approaches its 200th anniversary.

Interestingly, it means that all three honorary positions at the RSA are now held by Dundee-artists as Delia Baillie has been elected treasurer and Edward Summerton has been elected secretary.

Mr Fisher was elected president at an assembly of academicians.

He took up office on November 22 as Joyce W. Cairns PPRSA completed her four-year presidency.

Long history of RSA

As an independent, membership-led organisation, the RSA is governed by its 120 academicians who are all pre-eminent in the disciplines of art and architecture.

While the RSA is an incredibly historic organisation that looks after its members, it’s always had the interests of young artists at its heart.

“It was started in 1826 and oddly enough it was actually in existence before the National Galleries of Scotland,” he says.

“Gradually as it grew and the National Galleries of Scotland began we started to share the same buildings on The Mound.

“Another important thing about the academy is the historic collection of artwork that we hold.

“But as well as supporting members and building that collection, the academy does a lot for young artists as well.

“We support a lot of residencies for young artists.

“We offer an annual prize called the John Kinross Fellowship which uses money that was bequested by Mr John Kinross some time ago.

“That money allows students to travel to Italy and spend time in Florence.

“We also have what is called the annual New Contemporaries show which supports emerging graduates from art school.

“So it’s historic but it’s also very supportive of up-and-coming new artists, and of course, it’s very supportive of its members.”

To find out more about the Royal Scottish Academy, go to www.royalscottishacademy.org/

Conversation