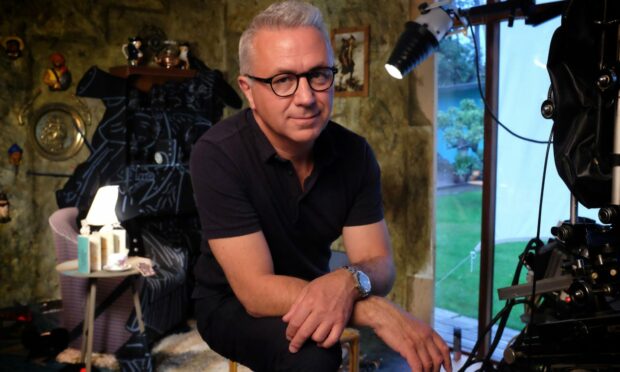

Michael Alexander speaks to Dundee Professor Calum Colvin who recently had an iconic group portrait unveiled at the British Academy in London and whose previous work has featured Robert Burns, Michael Marra and Andrew Carnegie.

From failing his ‘O’ grade art at school to photographing some of the most iconic figures of recent times, the creative road travelled by Dundee professor Calum Colvin has been a momentous one.

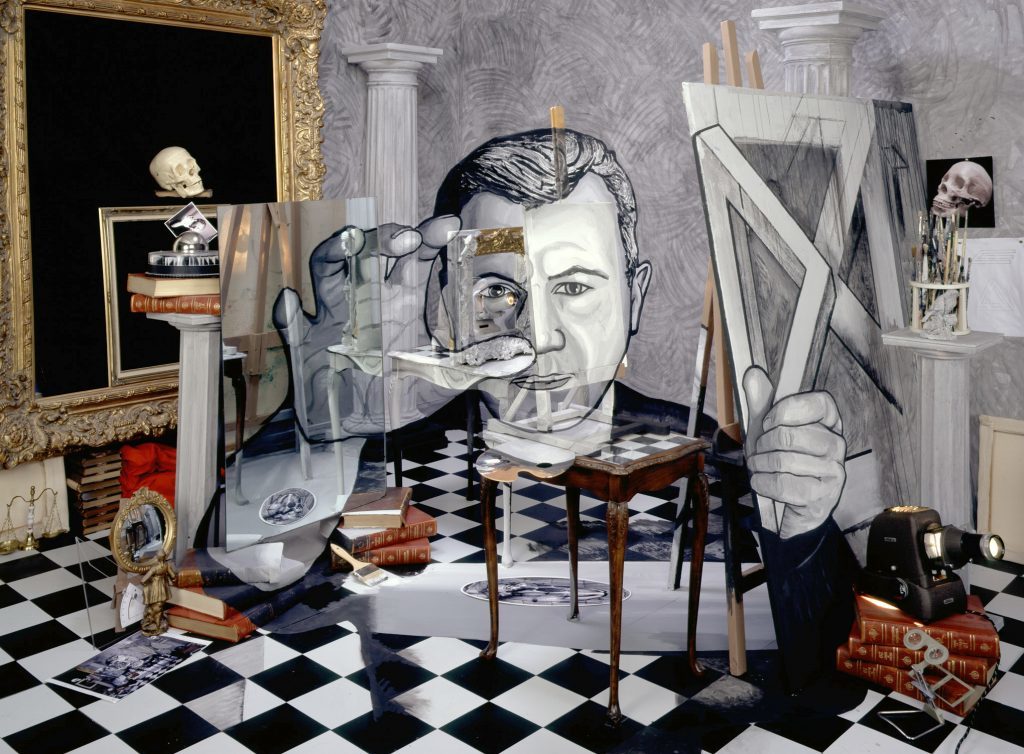

The professor of fine art photography at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design is one of Scotland’s leading contemporary artists, renowned for his intricate constructed photography.

How did he discover photography?

He discovered photography in the 1980s under the mentorship of documentary photographer Joseph McKenzie while studying sculpture at Duncan of Jordanstone.

His work graduated quickly from early emotive black and white images of desolate subjects to layered installations, taken with a large field-camera, carefully composed over up to three months.

Having exhibited extensively in Europe and the USA, he’s worked on commissions for several major galleries.

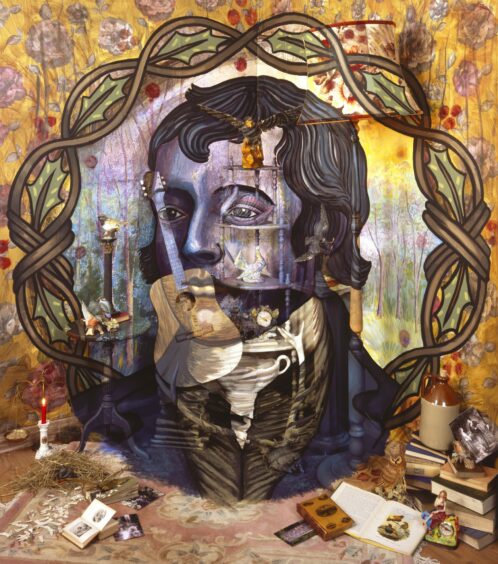

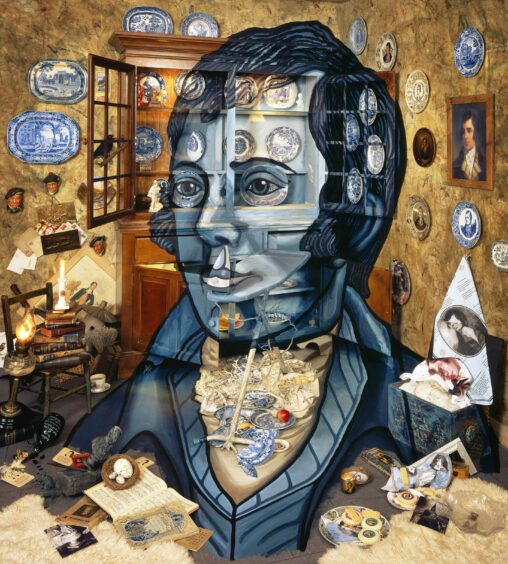

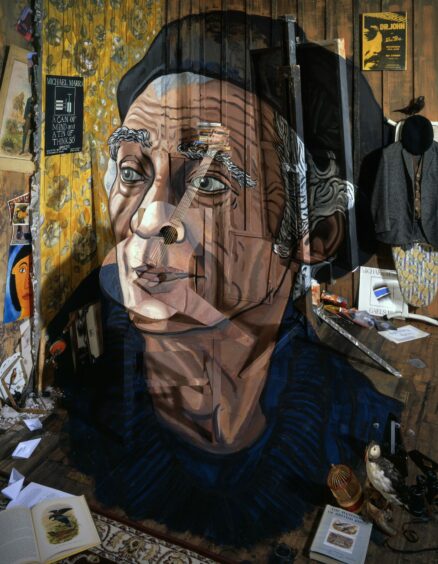

Iconic portraits have included Dunfermline-born entrepreneur and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, the late Dundee musician Michael Marra and several works of Robert Burns.

These include a new piece this year made exclusively for the National Galleries of Scotland.

It’s entitled Calum Colvin “Burns – After Flaxman” 2023 and will be launched at a special Burns Night concert at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery on January 25.

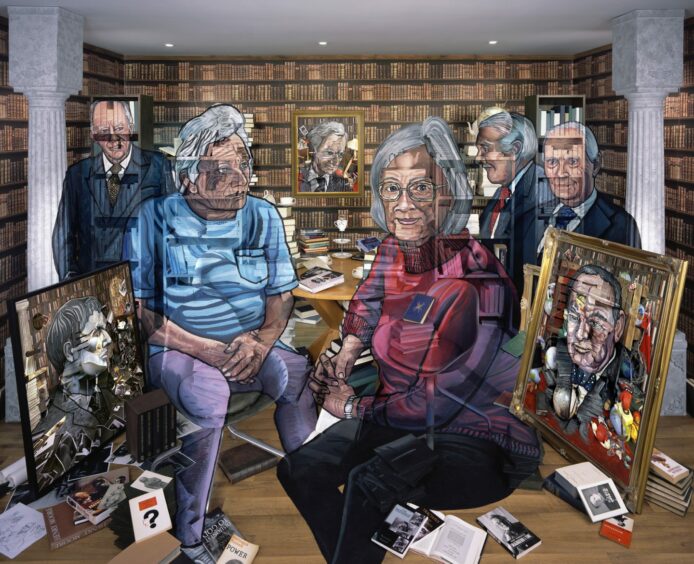

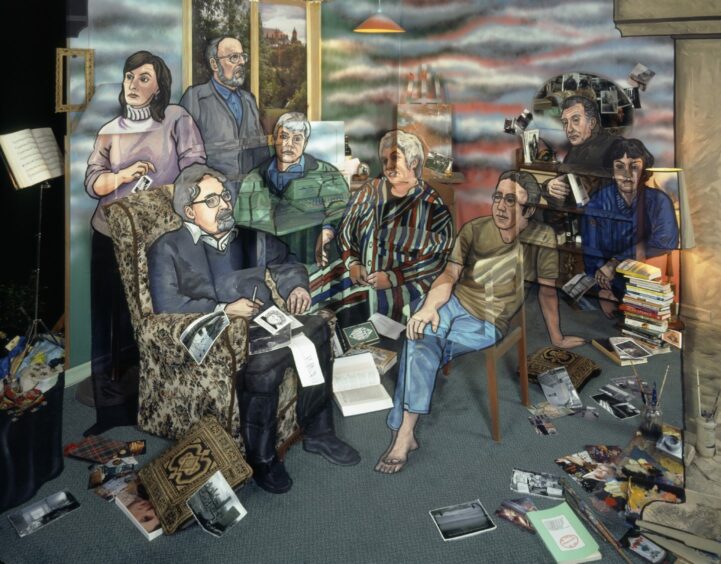

Perhaps one of his most time-stretched commissions, however, is a group portrait recently unveiled at the British Academy in London entitled ‘Honorary Fellows: Past and Present’, to help the institution mark its 120th year.

It features historical figures such as Bertrand Russell, Sir Winston Churchill and Henry Moore alongside contemporary Honorary Fellows Baroness Brenda Hale, Baroness Mary Warnock and Lord Rothschild.

‘World’s slowest photographer’?

Speaking to The Courier about his work, Professor Colvin said he was first commissioned to do the portrait of honorary academicians for the British Academy back in 2015.

He laughs that this timescale must make him the “world’s slowest photographer”!

However, after overcoming delays brought on by falling off his bike and breaking his hip, as well as the impact of Covid-19, the commission was worth the wait.

“When they first approached me about doing a portrait of honorary academicians, they spent quite a lot of time negotiating who these people might be,” he says.

“As you can appreciate a group portrait is technically quite an involved thing. It takes a lot of planning.

“Once they worked out and gave me a list of all the people that they wanted me to do this group portrait of, it was really just a question of making arrangements to meet those who were living and photograph them, and then just doing all the research on the historic characters who were no longer with us.”

Famous faces

Of the eight characters featured, the three most famous were historical – former Dundee MP and Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, artist Henry Moore and philosopher Bertrand Russell.

They’d all had some kind of honorary fellowship and some involvement in the funding and promotion of the British Academy.

Of the more contemporary figures, the only two he met were Baroness Brenda Hale, former president of the Supreme Court, who he photographed at the court in London, and philosopher Baroness Mary Warnock who he photographed at her home, and who has since died.

A portrait of world-famous Antarctic explorer Captain Scott, created by renowned Scottish artist and Head of Contemporary Art Practice at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, @CalumColvin , was unveiled at Discovery Point on Saturday! https://t.co/ELubYmgC1W #DJCAD pic.twitter.com/2OBPwG7Ksu

— DJCAD, UoD (@DJCAD) May 28, 2018

The other people involved were Lord Jacob Rothschild, Lord Leonard Wolfson and Dr Marc Fitch.

For them he worked with supplied images.

The piece, launched at the British Academy on November 8, ended up being an “enormous” two metres long by 1.5 metres high.

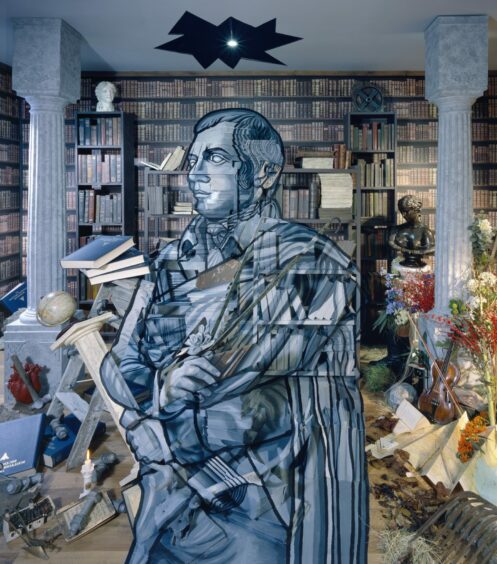

It’s a fine example of Professor Colvin’s complex constructions composed of three-dimensional stage sets, populated by everyday household objects and overpainted with subjects that relate to fine art, popular culture, global history, identity and ecology.

But how does he decide what goes where?

“That’s a good question,” he says, “because essentially there’s your conception of the subjects in any portrait.

“You are deciding how they might relate to each other.

“Then there’s the visual factor in terms of how’s it going to work in terms of composition, and there’s relationship and balance.

“It’s part visual and it’s part intellectual in the sense of what you are trying to do with everything. It is very tricky shall we say!

“At a certain point you have to commit because I am essentially assembling a whole lot of furniture – in this case loads and loads of books and lots of props.

“And then you’ve got drawings – you are trying to figure out how this painting is going to go over the props, how that’s all going to work.

“At a certain point the paint brush comes out and you start working.

“At that stage you become a little bit limited in what you can change.”

Evolving organically

Professor Colvin says that with any artwork, he spends a lot of time trying to visualise the finished piece.

But eventually pictures evolve organically.

Sometimes he just “goes with it and hopes for the best”.

“My work really becomes a kind of a reconciliation between what the human eye sees and what the camera sees,” he says.

“In that sense I have to work away and change things, adapt to change the lighting.

“I spend a lot of time finishing the work until I’m either really happy with it or I’ve lost the will to live!” he laughs.

“It’s so kind of intense the whole process. But I do love it. I love working in that way.

“It’s not the only way I work, but it’s kind of to my mind the purest way of working and the simplest.

“I know that sounds a bit odd because the works visually are very rich and very complicated.

“But actually in terms of structure, they are quite simple, and that’s what the viewer likes.

“People look and they see a whole lot of information, a lot of colour, see all these lines and everything.

“And then their eyes adjust and they start figuring out what it is they are looking at, and then they are involved in a dialogue with the artwork.

“I think that’s what people enjoy about them. It’s a combination of a simplicity with a visual complexity.

“If I can get that balance right, that’s when I think the work is successful.”

Exploration of technique

In art history, tempera – a technique of painting with pigments mixed in egg yolk or glue – was widely used for layering before being superseded by oil paints in Renaissance Europe.

A number of artists have played around with the technique in relation to photography.

Young Calum Colvin started working in that style as a student at Duncan of Jordanstone around 1982.

As a student of sculpture, he was also very into photography and wanted to see if he could bring the disciplines together to make photographs.

While his mentor Joe McKenzie probably wanted him to investigate the “documentary style” of photography, Calum, who describes himself as “very stubborn” was more interested in colour, photography and “hybrid practice”.

He went to London to do a masters degree in photography at the Royal College of Art.

After graduating in 1985, he was offered an exhibition the following year at The Photographers’ Gallery and has been in “the right place at the right time” since.

“My career just took off from that and since then I’ve never been without some project, without some exhibition, without some commission,” he says.

“I’m very grateful for that. It’s not easy being an artist – it’s a lot of hard work.

“You spend a lot of time on your own.

“But if you have deadlines and you have commissions and you have people who support you and encourage you, it’s a no brainer – it’s what you do.”

Development of career

Born in Glasgow in 1961, Professor Colvin has exhibited his work nationally and internationally for over 30 years.

The first portrait he did was of composer James MacMillan in 1996, commissioned by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

This “awoke an interest” in him.

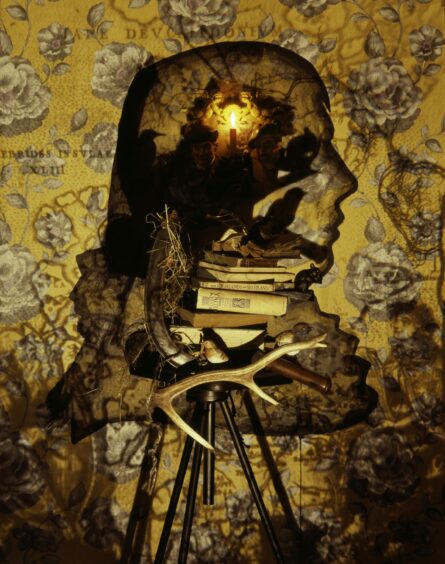

Historical portraiture later entered his practice through Robert Burns, which proved very popular.

In 2000, he was commissioned to do a group portrait of contemporary Glasgow writers, known as the Kelvingrove Eight.

He was a winner of one of the first Scottish Arts Council Creative Scotland Awards from which he created the acclaimed exhibition for the SNPG ‘Ossian, Fragments of Ancient Poetry’ in 2001.

He was awarded an OBE the same year.

Honouring Michael Marra

Immersing himself in Dundee’s rich culture and heritage, he was honoured to work with and become good friends with the late musician Michael Marra.

An admirer of Marra’s musical talents and sense of humour, Colvin later produced a portrait for an exhibition at the McManus.

“Peggy Marra allowed me to make a little display of some of Michael’s stuff – his archive, some of his hand written songs, but also the iconic ironing board keyboard stand,” he says.

“I was able to use those in the picture I made of Michael. It’s unfortunate of course that we lost Michael in his prime.

“I would have loved to have been able to show him that picture and talk to him about it, but it wasn’t to be.”

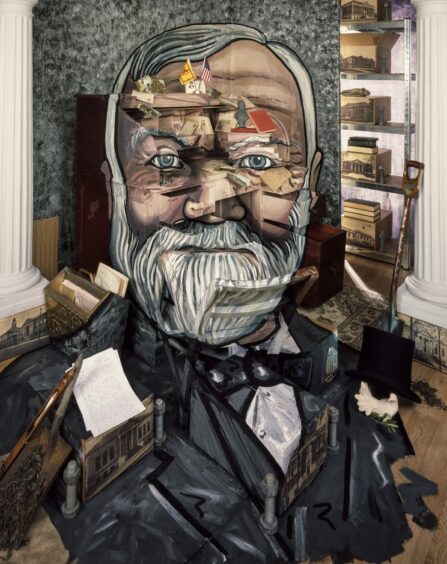

Tribute to Andrew Carnegie

In 2019, Professor Colvin also followed in the footsteps of pop art pioneer Andy Warhol in creating a portrait of Andrew Carnegie.

The work, unveiled at the Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum in Dunfermline, was the first portrait of the Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist Carnegie since Warhol’s famous 1981 effort.

The portrait was commissioned by the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust to mark the centenary of Carnegie’s death as well as the continuing worldwide philanthropic scope of the institutions he endowed.

Dundee has ‘best art school in Scotland’

A lecturer at Duncan of Jordanstone from 1993 to 2001, a professor since 2001 and Associate Dean of Research since 2018, Professor Colvin firmly believes Duncan of Jordanstone is the best art school in Scotland.

As someone familiar with the “lonely path of the artist in the studio”, he takes great satisfaction from teaching and talking to students when he can.

When he reflects on his career, however, he smiles at how he failed his ‘O’ grade art as a high school student in North Berwick.

“I still think they lost my work or something went wrong,” he laughs, revealing that he wanted to be a cartoonist as a child, and only went to Duncan of Jordanstone after failing to get into Edinburgh College of Art.

“I thought maybe I’d go into writing. I was always really interested in poetry and literature.

“I wasn’t particularly academic as a child.

“I did always have an interest in art.

“When I failed ‘O’ level art, my confidence took a bit of a dent.

“But I stuck in. It really gave me a wake-up call as a young person thinking ‘you know I’ve really got to apply myself’.

“I was only 17 when I came to art school at Duncan of Jordanstone. I was just a laddie!

“But my dad couldn’t bare the idea of having an idle teenager in the house any longer, so he more or less told me ‘you are going to Duncan of Jordanstone whether you like it or not’!

“As soon as I came to Duncan of Jordanstone and got involved in the art school, there was no going back for me. I absolutely loved it here, and still do.”

Advice to today’s students

Professor Colvin has no regrets about how things have worked out and continues being a great ambassador for the college.

If he has one piece of advice for today’s art students, however, it’s “never say no” if approached to do work.

“Never say no because you never know if something is going to be interesting, or how it’s going to pan out,” he adds.

“You might get offered four jobs then three of them fall through.

“I’ve always been very open to things and having conversations with people you might not normally.

“If you don’t want to do something, just put the price up!”

Conversation