It is the language that Courier columnist and Scots language expert Alistair Heather once described as the “partially submerged language of a partially submerged nation”.

Scots, known as the “mither tongue” is spoken by over 1.5 million people in Scotland, principally in the lowlands and northern isles.

It’s been the language used by government, kings and courts in Scotland, as well as by poets and playwrights like Rabbie Burns and Rona Munro.

Yet in the latter half of the 20th century, Scots began to be seen as vulgar, or common, and has been denigrated as ‘slang’ or ‘ned speak’.

A rediscovery of cultural confidence in the last decades has seen a marked increase in the quality and quantity of creative projects appearing in the many dialects of Scots.

The Scottish Government has announced it’s introducing the Scottish languages bill to legally recognise Gaelic and Scots and to protect minority languages within communities.

This will include legislation designed to protect and promote the Scots language, alongside Gaelic.

So if the language is so deep rooted, why does so much hostility seem to persist towards the promotion of Scots, particularly on social media?

Has it become too politicised?

More should be done to protect Scots language and heritage

Dundee theatre maker Taylor Dyson, 28, and her partner Calum Kelly have toured their Dundonian Scots show ‘Ane City’ across Scotland and internationally, as well as bringing shows to grassroots venues throughout Dundee.

Taylor says the question shouldn’t be ‘should Scots be protected and encouraged?’ but rather ‘why aren’t we doing more to protect something that is part of our cultural and historical heritage’?

“The history of our language is our history, and it informs our contemporary culture,” said Taylor.

“Why would we deny ourselves knowledge?

“Scots was the language of Scotland: the monarchy, the parliament and law.

“But, due to political shifts and the standardisation of culture and heritage that was attempted, we have hundreds of years of eradication and shaming of folk for speaking in their natural language.

“This still has an impact on people today who are made to feel unprofessional or branded as non-educated, but why?”

People are ‘shamed’ and ‘automatically judged’ if they speak Scots

Taylor says that unfortunately “classism” is very much alive in 21st century Britain.

Anyone who isn’t speaking in standard English is “shamed” as somehow being lesser.

Even the hint of a thick accent and people are “automatically judged”.

“From experience,” she said, “I can say that I’ve encountered many Scottish people going into the performing arts over the years and they will tell you first hand they are told to soften their accents – less they be deemed unemployable.

“And you may think ‘fair enough why can’t they just speak plain English?’.

“The answer is plainly – they don’t – they never did.

“These Scots speakers exist and whether you approve or not, they aren’t going away.

“Why can’t we embrace our uniqueness?

“Tak a daunder doon ony street in Dundee, and yi’ll hear Scots still spoken, and eh for one love it.

“It maks me feel closer to meh faimly, to where Eh’m fae and allows us and mony ithers tae express creatively in an authentic wiy.

“Why should we stamp oot authenticity in order to mak everyone and everything the same?

“We need to continue to celebrate, protect and encourage oor uniqueness, stop politicising things and stop picking apart language when it’s somethin’ that doesnae need picked apart. And aye, Scots is a language.”

Taylor says that within the field of linguistics there is no standardisation of what separates language and dialect. She believes Scots has the people on its side.

She added: “Fae Burns tae The Big Yin, Men Should Weep or Still Game, Scots is a part o’ wir culture and oor history, and despite their being numerous attempts at eradicating the language, it’s richer than ever.

“So let’s champion oor language and allow it, and it’s speakers to thrive.”

Does the spoken and written word of the Scots language have a future?

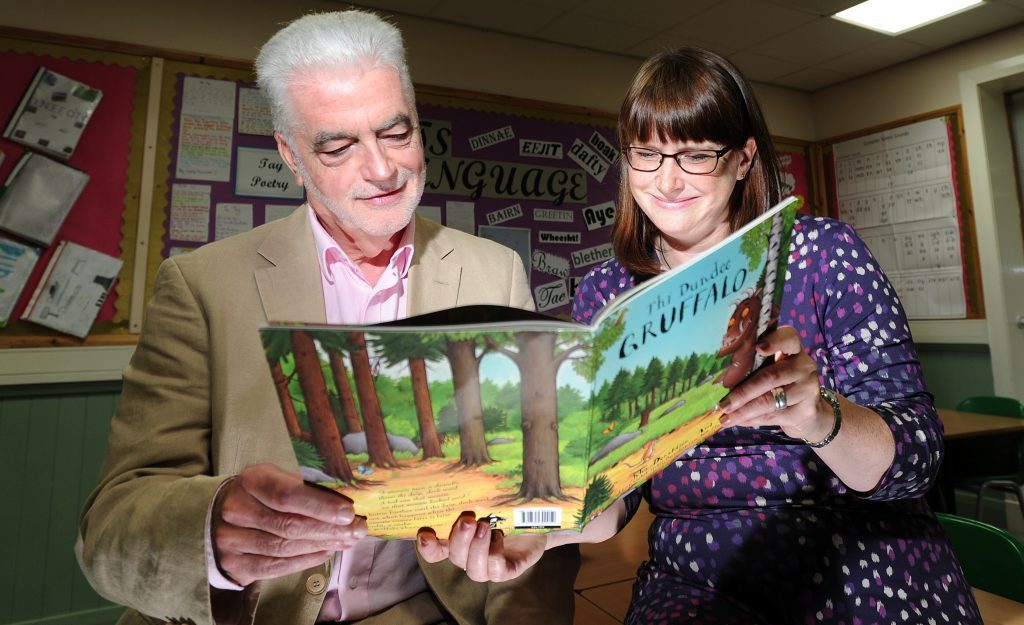

The majority of Dundonians that city sports pundit and Courier columnist Jim Spence knows are bilingual.

He slips between standard English and his dialect depending on the company.

While he’s not overtly against trying to sustain Scots, he does think there’s a difference between the written and spoken forms of the language.

“Old Scots Law statutes which have fallen into disuse through the passage of time are said to have fallen into Desuetude,” he said.

“The same hasn’t happened to the Scots language.

“But there’s still a danger that much of the ‘mither tongue’ might disappear as the world becomes more globalised.

“I’m not convinced that government intervention to encourage and protect the Scots language would be successful, although I’m not against it.

“However, attempts to use the language as a political and cultural tool as a method of signifying our distinctiveness will find a limited audience I suspect.

“Spoken Scots I think has a much better chance of retaining good health than the written word.”

What is needed for the Scots language to grow and prosper?

While in many areas of Scotland the dialect is still spoken in daily conversation, Jim seldom sees written Scots.

When he does he has to work hard at understanding much of it, since it’s often very different from the dialect that he uses in Dundee.

“For spoken Scots to grow and prosper,” he said, “it would need regular mainstream broadcasting involvement, and I don’t see BBC or STV or the various radio stations offering anything other than token programming which will have limited effect.

“I’m not sure that this particular patient can be kept alive if there’s not the willpower of those required to relearn it in its written form.

“The spoken word seems to me to be in more robust health than the written one.”

All languages and cultures change over time, added Jim.

He’s read that the traditional Cockney patois of London is also changing dramatically with the transformation in demographics in the capital.

He knows younger folk in his circle who don’t use the Dundee dialect and he suspects they never will.

“They understand it obviously,” he added, “but it’s not an integral part of their daily lingua franca.

“I’m not sure what kind of encouragement or persuasion can change that.”

Grant funding for Scots language creatives available

A new source of grant funding for Scots language creatives is open for applications.

The fund, provided by Creative Scotland and administered by Hands up For Trad, offers grants of £500 to creatives producing work for audiences using the Scots language.

‘Wee Grants for Creativity in the Scots Leid’ are open to everyone – individuals and groups – and can be used to support audience-facing creative work of any kind.

There is £10,000 to distribute, meaning that twenty applications will be successful.

Applications are made through the Scots Language Awards website, https://projects.handsupfortrad.scot/scotslanguageawards/

Conversation