Twenty six years after the end of the Cold War, volunteers from Dundee and beyond are working to protect a relic from the past that’s closer to home than many people might think. Michael Alexander went underground to find out more.

At the end of a quiet modern cul-de-sac off Craigiebarn Road in Broughty Ferry, an unremarkable wooden gate leads to an unremarkable-looking low-rise building with a battered blue door.

To the right of the entrance the only sign that something unusual can be found here is a large raised area of grass with some rusting metal vents protruding.

But it belies the scale of the former three-storey Royal Observer Corps (ROC) monitoring post buried 20 feet underground.

Until 26 years ago, the bunker would have been on the front line in the event of a nuclear attack on the UK, providing a place for 80 men and women ROC volunteers to measure nuclear blast waves and radioactive fallout.

Between 1956 and 1965, the UK government ordered the construction of 1,563 monitoring posts at a distance of about 15 miles apart including the likes of Cupar, St Andrews and Arbroath.

Thirty-one larger HQ and control centres – like the 28 Group HQ in Dundee – were also built.

As the Cold War came to an end with the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the sites were all closed down when the ROC was stood down in 1991.

Many of the sites were subsequently demolished or fell into disrepair.

But some have been preserved by private individuals or trusts, including the restoration project team 28 Group Observed which has spent more than a decade helping to restore the Dundee complex which is the only remaining Royal Observer Corps sector bunker left in original condition in the UK.

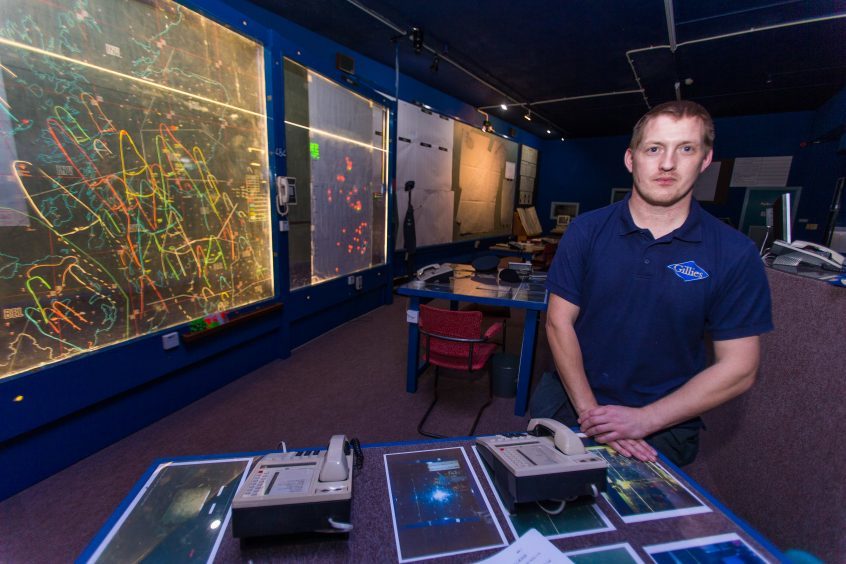

The Courier was invited to join bunker manager Gavin Saxby – a systems engineer based in Edinburgh – and volunteer Steve West, from Forfar, on a tour of the remarkable complex, which was designed to be self-contained for months after a nuclear strike.

Unlocking the outside door and passing through the blast proof door within, Gavin, 40, takes us on a journey down the main stairs past the airlock and into the bunker which comprises a maze of corridors and rooms on three levels.

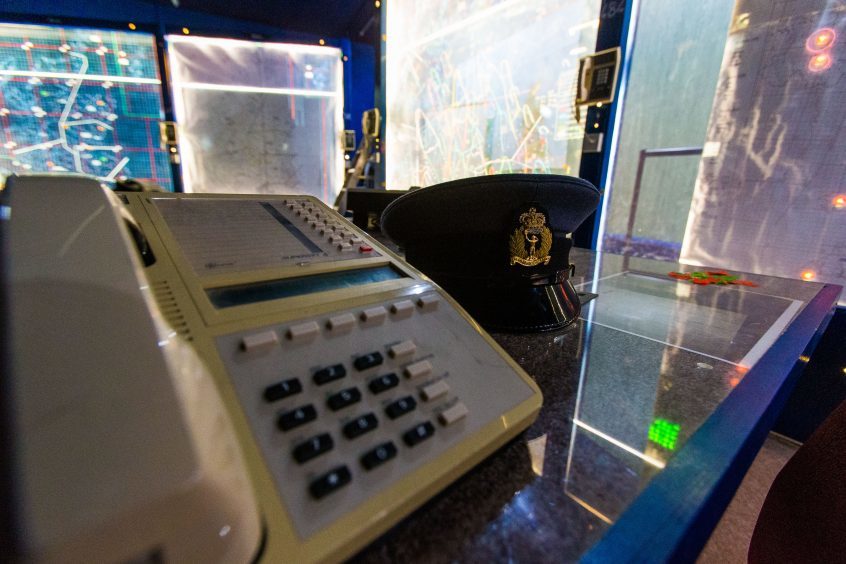

Highlights include the sewage ejector room which is still in working order, the plant room, the switch gear for the fans and the ROC operations room which has been kitted out with some of the original communications and monitoring equipment that would have been in use during those Cold War years.

From there it’s on to the men and women’s dormitories, the first aid room and the radio room which includes an old style Tele-talk and carrier receiver.

The tour ends in the sector operations room which includes simulated maps of fallout from nuclear strikes on Scotland, as it might have been if the Soviets had ever attacked and the apocalypse of World War Three had commenced.

“We are standing in the sector operations room of the bunker which is where the observers and some civilian scientists would have taken information gathered from all around Scotland and used it to plot the path of fallout as it moved across the country,” explains Gavin, who started working on the restoration of the bunker in 2004 after hearing about it when he joined Subterranea Britannica — a group committed to the study of man-made underground places.

“There were 25 bunkers of this size around the UK for each of the 25 groups and then those 25 groups were split into five sectors of the country. This bunker, which was built in the early 1960s, ran the whole of Scotland which was called the Caledonian sector.

“It was originally to run the smaller ROC bunkers dotted all around the Dundee area. There were around 50 in the area at that time.

“The little three roomed monitoring bunkers were designed to gather a couple of basic bits of information during a nuclear war.

“They would be able to tell the direction and the height of nuclear bomb bursts.

“They would have been able to tell the pressure that was caused by the bomb burst and they’d have read the levels of radiation post-strike.

“All of that information was gathered up, sent every five minutes back to the HQ bunker here in Dundee and then it was all plotted out on the screens so that the armed forces and the civilian government were able to work out which bits of the country needed to have air raid sirens sounded, which bits needed fallout sirens.

“After the event they would have been able to tell which areas were just too radioactive for people to go into.

“If troops needed to go around to help people, they could be diverted around the ‘hotter’ areas to keep everybody as safe as they possible could be after a nuclear war.”

Gavin explained that the Dundee complex would have had a close relationship with what is now the Scotland’s Secret Bunker tourist attraction at Troywood near Anstruther.

“The civilian government (at Anstruther) would have required information from here to ensure people moving around the country could do so fairly safely,” he adds.

Throughout the Cold War the Dundee bunker was opened up for exercises to simulate nuclear scenarios.

However, if a point had arisen where war was inevitable, it would have permanently housed 80 or 100 ROC volunteers.

Gavin said most of the smaller monitoring bunkers were in rural locations and rather inconspicuous.

But he is not clear how many people knew the larger Dundee bunker was there.

“The most common phrase I hear now is “I had no idea that was there”,” he says.

“The big mansion house upstairs was just a house before and then the permanent ROC offices had it as their office. It was a fairly big set of grounds it was built in. I don’t think a lot of people cottoned on.

“That said there’s a big sign down on the main road that says ROC civil defence and Air Cadets.

“The signs were there but it’s one of those things that if people don’t think about it they don’t notice it.”

Gavin said that when the preservation group took over the bunker, the operations room for example was little more than an empty concrete box.

Since then, however, thanks to donations from the likes of English Heritage, many genuine fixtures and fittings from other bunkers have helped with restoration.

Other items have been made from scratch.

“It’s been a decade long search for weird and wonderful little things that are around the bunker,” he says.

“It’s getting the right kind of wax pencils; the right paperwork; going and using modern tools like Illustrator, Excel and Word to create some of the charts we see on the wall; going to other sites, photographing things and measuring.”

However, given the age of the building, maintenance is an on-going issue. Two years ago, for example, a perished rubber washer on a water heater caused a horrendous flood.

Gavin is really pleased with the amount of progress that’s been made thanks to an “amazing pool” of volunteers – including some former ROC members.

And with the likes of the Arbroath ‘Royal Observer Corps Monitoring Post’ Museum already in existence, he hopes that one day the Dundee complex can be opened up to the public.

He adds: “Being in the middle of a housing estate we have to be very very sympathetic to our neighbours.

“I don’t think we’ll ever open up as a kind of free for all museum.

“What I’m aiming for is pre-arranged visits – maybe a minibus sized group of people – to get a completely personalised tour.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l9ETEEWW5eU

“I’m thinking cadets, scout groups, schools that are studying the Cold War – that kind of thing.

“People might be interested to know, however, that having looked sat the structure of this place inside out, I’m not convinced what the chances would actually have been of withstanding a nuclear attack!”

*28 Group Observed are always looking for new volunteers and donations from tradesmen to help with the project. To get in touch via Facebook go to www.facebook.com/28group