Following the UK’s recent £100 million pledge to help eradicate polio worldwide, and release of the film Breathe, Michael Alexander meets polio survivors in Tayside who are helping to raise awareness of Post-Polio Syndrome.

It was once the most feared of diseases that was all but eradicated in the UK when routine vaccination was introduced in the mid-1950s.

The serious viral infection, which has no cure and is still a serious problem in parts of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria, causes temporary or permanent paralysis for up to one in 100 of those who catch it through contaminated food, water droplets or faeces.

But while there hasn’t been a case of polio caught in the UK since the mid-1990s, that doesn’t mean that polio is not still a problem for the people who contracted it years ago, survived it and are now growing older with it.

The emergence of Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS) has become another threat to the health of polio survivors in Britain, according to the Scottish Post-Polio Network which campaigns to raise awareness.

The Courier caught up with members of the 30-strong British Polio Fellowship (Tayside Group) who hold monthly social meetings at the Woodlands Hotel in Broughty Ferry.

One of the worst aspects of PPS, members of the Fellowship say, has been the difficulty in getting it recognised and therefore the difficulty in getting a diagnosis.

The average age of Scotland’s estimated 10,200 polio survivors is 69, and it’s estimated that 60% of them suffer from PPS.

Symptoms include weakness, muscle wasting and pain in parts of the body that they did not realise had been affected by the virus.

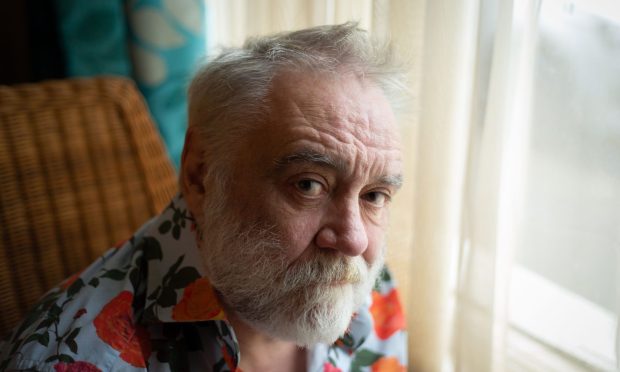

One of those experiencing a resurgence of symptoms is retired office worker Bill Fenwick, 67, who worked in Dundee City Council’s insurance and risk management section for 35 years.

Diagnosed with polio as a baby, it largely affected the development of his right leg and the former pupil of Ancrum Road and Logie schools wore callipers up to the age of 12. Despite experiencing his fair share of bullying at school, the grandfather-of-two managed to lead a relatively normal life, going on to hold down a full time job and raise a family.

However, in the last 10 years, Bill has noticed a deterioration of his condition and again wears callipers to help him walk.

“In the past 10 years or so it’s the secondary effects of polio that have come to be more of an issue,” he says.

“Things like joint pain, deteriorating strength in the limbs, breathing issues, sleeping patterns disrupted.

“It’s partly the natural ageing process but I think because I had polio things are a bit more extreme.”

Ann Robertson, 82, of Broughty Ferry was 21 years old and working as an occupational therapist at a psychiatric hospital outside London when she contracted polio just a fortnight before she was due to be married.

Living in digs, she had all the symptoms of polio – including headaches and back pain.

However when she went to the doctor and suggested she had the virus, she was told it was “pre-wedding nerves” and sent away with pain killers.

Hours later, when she collapsed at a friend’s wedding, her husband-to-be Norman, from Perth, took her to his then doctor near St Albans and she was immediately admitted to a hospital isolation unit – forcing her own wedding to be postponed by several months.

“My brother gave me away on my wedding day – I walked down the aisle hanging on to him because I was determined not to take my crutches!” says Ann who doesn’t know for sure how she acquired the condition but thinks it may have been through contact at a dirty swimming pool.

“I was left with a weakness in my left leg. But thanks to my husband being shown how to stretch all my muscles I managed to live a very normal life – I still managed to have three children, go hill walking – I just couldn’t run!”

Like Ann, Lyla Scott, 51, from Dundee, has recently been diagnosed with suffering from PPS.

But as one of the youngest members of the Tayside fellowship, Lyla’s case is different in that she caught full blown polio from the vaccine after being given the then jab as a three month old.

“It affected all my limbs to begin with but mostly in my legs,” says Lyla, who wore metal and fibre glass callipers on her legs throughout childhood then underwent a series of painful operations in her 20s to lengthen her legs.

“The government of the time said there was a one in 2.5 million chance you could get polio from the live virus. I was that one in 2.5 million! My mum still blames herself, but it wasn’t her fault at all – I was deemed to be the ‘acceptable risk’.”

Lyla’s parents were initially told she might not live and would never walk. But Lyla, who depends on an electric wheelchair, has proved those 1960s doctors wrong.

“The British Polio Fellowship has been a godsend,” says Lyla who was forced to retire from her job with Hillcrest Housing due to the onset of PPS aged 42.

“You think you are on your own – then you come here.”

Lyla says it’s essential that parents ensure their children are vaccinated against polio to mitigate against future outbreaks.

However, she’d like to see greater awareness within government and the NHS about PPS.