Researchers based in Dundee have discovered animal camouflage is more effective than previously thought.

A team from Abertay University discovered animals which utilise their skin to blend into their surroundings – such as pythons, moths and frogs – can again alter their appearance even once they’ve been spotted by potential predators.

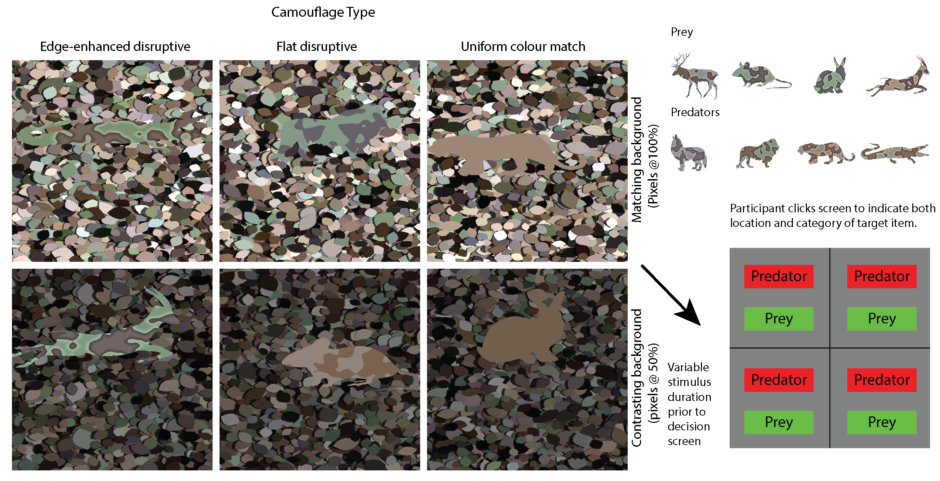

Creatures who use camouflage, or “edge-enhanced disruptive colouration”, can in essence “hide” from bigger animals who want to eat them by changing how they appear in their surroundings.

A similar technique has been employed by armed forces around the world since the 20th century, with the wearing of combat fatigues covered in seemingly random patterns which effectively break-up the outline or silhouette of the person wearing them.

The study, compiled by researchers at Abertay University and Stirling University, challenges the theory that a predator immediately recognises its prey as soon as they see it.

The report, which is to be published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports, reveals the appearance of animals with “edge-enhanced disruptive colouration” – where dark patches of camouflage have darker edges and light patches have lighter edges – is difficult for others to identify.

The findings show, for the first time this pattern of colouration – which gives the impression of varying surface depths and shadows – appears to slow the process of recognition and, consequently, makes animals harder to identify.

The study was conducted by Dr George Lovell, a lecturer in psychology at Abertay, Dr Rebecca Sharman, a research fellow in psychology at Stirling and Stephen Moncrieff, a BSc (Hons) forensic psychobiology student at Abertay.

Dr Lovell said: “The theory that disruptive colouration might impede recognition has been part of biological textbooks for decades. It is great that we finally have some experimental support for this claim.

“Developing effective camouflage has obvious military applications, but it is also used for town planning, architecture, fashion, conservation, and bird-watching, amongst many other things.

“Surprisingly, most military camouflage is not developed on the basis of empirical evidence and, as such, research of this kind has the potential to really make a difference to the safety of personnel.”

Dr Sharman said: “In the past, it has been assumed that if you can detect where a target is, you must also know what it is.

“For the first time, we show that this is not the case.

“Edge-enhanced disruptive colouration not only makes targets harder to find, but also harder to identify – just because you know where something is, does not mean that you know what it is.”