In an exclusive sit-down interview to mark the opening of the V&A Dundee, Michael Alexander speaks to the world renowned architect and designer of the building Kengo Kuma about his inspirations and hopes for the project.

When Kengo Kuma was being interviewed last year about designing the £1.2 billion stadium for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, he admitted that he sometimes feels a “bit embarrassed” by some of his buildings.

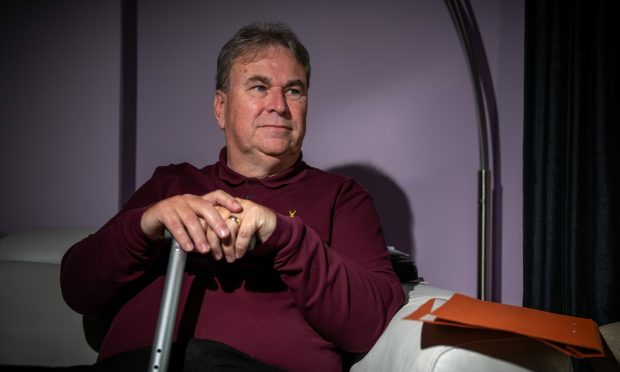

But seated in one of the viewing galleries at Discovery Point over-looking Captain’s Scott’s ship RRS Discovery – and Kuma’s striking V&A Dundee building beyond it – he is far from embarrassed about his Tayside creation.

In an exclusive interview with The Courier ahead of the opening of V&A Dundee on September 15, the world- renowned Japanese architect, whose firm KKAA won the commission to design the building in 2010, said the principles of angular walls tested for the first time in Dundee had actually influenced the design of the £1.2 billion 2020 Tokyo Olympics stadium.

He said advances in software, that calculate the balancing stresses and counterweights to gravitational forces, had liberated architecture and could now influence all subsequent landmark buildings around the world.

“It’s not an easy building,” he said of the V&A Dundee as he gazed out at the landmark building.

“The construction brought many challenges with the construction, details, the geometry. The location was very challenging as well – to have the building by the water.

“The final quality is very beautiful and I’m very happy to see its completion.”

The V&A Dundee comprises a gravity-defying array of angular geometrical shapes.

It is fashioned out of a delicate 300mm-thick concrete shell that was incapable of supporting itself without scaffolding, until bound together by a giant roof-span.

Unlike other iconic and revolutionary abstract-shaped buildings, the V&A Dundee has no steel frame or internal pillars providing skeletal support.

Mr Kuma explained that the design of the V&A Dundee was inspired by his travels around the Scottish coast, and in particular the sheer sedimentary cliffs that inspired the concrete slats that cover the angular concrete double box design of the new museum.

Other influences include the prow of the RRS Discovery permanently berthed alongside the new museum, and – in the space between the two main blocks, a Japanese “torii” gate, the traditional entrance to a Shinto shrine, such as the iconic red sea-gate at Miya-jima in Hiroshima prefecture, one of Japan’s most famous tourist attractions.

“When I came here to see the site I was impressed by the decision of the client to have the building at the edge of the waterfront, and the hope that the building could change the image of the waterfront of Dundee totally,” he said.

“We tried to find a unique solution for unique conditions. And our solution was to create a ‘gate’ between nature and city. In the 20th century architects thought architecture was a kind of isolated sculpture.

“In the 20th century, buildings resembled the white concrete box – and nature was totally separated. The separation was part of architectural design. But now people want to merge nature and the city.

“As a modern sculpture we need a relationship to make new other life. If people can feel nature is part of the city it can totally change the image of the city.”

Mr Kuma was familiar with Scotland through golf trips and felt a “strong sympathy” to being north of the border.

He felt the landscape of Scotland and peoples’ mentality was very similar to the ‘up north’ area of Japan – the Tohoku area which was badly destroyed by the tsunami in 2011.

“The craftsmanship of Tohoku area is best in Japan and also the area has many unique places,” he said.

“It’s the same with Scotland. Scotland is not one place – the landscape is very complex and many different places exist in Scotland.

“When I came here and did research about Dundee I found that life in Dundee is very much connected with the water and beyond water and the trade and the ships were very important for the culture in Dundee.

“So to have the ‘gate’ to activate Dundee again, that was the basis of the design.”

The inside of the building is also important. Through wood, for example, he tries to show the “essence, the spirit of the material”.

There’s also the concept of making the café area like a “living room for the city”.

“When I visited here in winters, the climate was very tough,” he said. “We began to think an internal public space was needed.

“The reason being that people are coming to the museum not only for art, people are coming to the museum to be relaxed. That kind of public space is very much needed in the city.

“In the 20th century, people always wanted to go back to their own living space.

“But now that people are together again in the public space in the city, our design concept of the interior of the museum is to create that kind of living room in the centre of the city.”

Of course, opinion has been split on the decision by Dundee City Council to grant permission for an office block adjacent to the V&A Dundee.

“I prefer not having buildings around these places!” laughed Mr Kuma when asked about it.

However, he added: “The waterfront of Dundee is totally changing and I’m very satisfied with the setting.”

He is also hopeful that the V&A Dundee will be the catalyst for the city’s regeneration.

The recent Dundee University honorary degree recipient said: “The ‘big city’ nowadays is very much standardised – the same bland shops, the same boutiques, the same hotel chains. People cannot find their own place in the big city.

“But in this size of city it has great potential in future. This kind of phenomenon is happening everywhere in the world.

“People find Dundee a ‘trendy’ city.

“Also visitors can experience a chemistry with the city. I hope this will happen in Dundee.

“It’s really a great honour for me to collaborate with this city.”

When Kengo Kuma was a student, he greatly admired the work of Scottish architect, designer, water colourist and artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

“I studied his detail and use of material,” he said.

“He is strongly influenced by Japan. He learned many of his ideas from Japan. That age at the end of the 19th century was a cultural exchange between Japan and Europe. They created many new ideas.”

Mr Kuma said many people forgot that cultural exchange during the 20th century.

But with the V&A Dundee’s permanent Scottish Design Galleries to include a complete reconstruction of a Mackintosh tea room – unseen for more than 50 years – he hopes it could inspire renewed cultural design direction in future.

“It’s a good thing for the museum to have Charles Rennie Mackintosh as a core exhibit,” he added.

“That reminds people how cultural exchange can lead us in a new direction of design.

“It is very good for both countries.

“If this museum can lead us to new direction in design, my role is complete!”