It was the shipment which signalled the end of an era for Dundee’s jute industry.

The jute ship Banglar Urmi docked at Dundee 20 years ago and discharged 310 tonnes of raw jute which was the last cargo to be processed in the city.

The bales were destined for the Arbroath Road spinning mill Tay Spinners, which was by then the last remaining jute spinning factory in Europe,

The 80 workers took until mid-December to process it, then their giant machines fell silent.

The closure brought an end to a jute spinning and weaving industry in Dundee, stretching back to the first half of last century, which spread the city’s name around the world and at its peak provided employment for some 40,000 people.

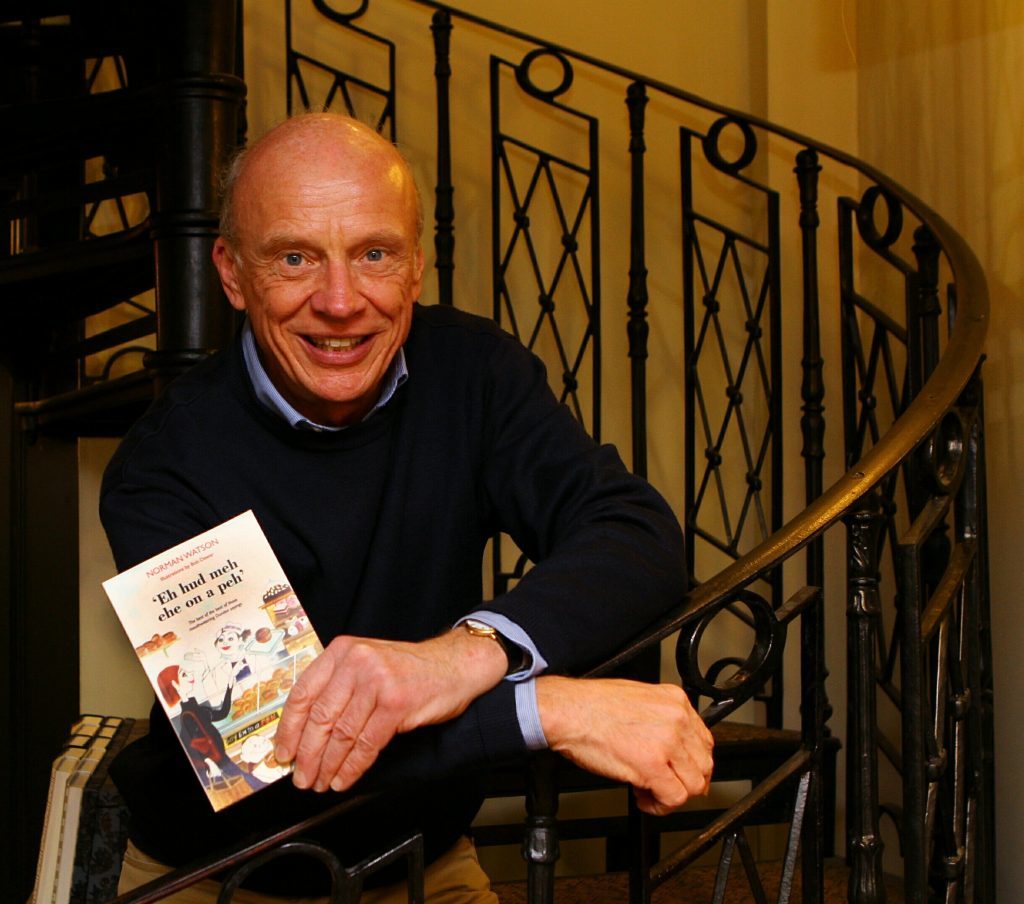

Journalist and author Norman Watson, who has written extensively on Dundee’s history, recalled a pilgrimage to Tay Spinners on the eve of its closure.

“I started work in Dundee in the 1970s in the fading light of its once mighty jute trade,” he said.

“Its one-time forest of chimneys were in the process of being felled, the survivors of 125 works were being rebooted with new businesses, the worst of the slum housing was being swept away – and eventually the clatter of the looms in Tay Spinners was the only sound of Juteopolis to be heard.

“I walked up from the town, opened a side door and was transported into the age of the endless rows of working people, the women, men and children who made the bobbins fly and the mills bustle.”

The Banglar Urmi was scheduled to arrive the previous month but was the subject of numerous delays on her voyage from Chittagong via Monglar, Calcutta and her last port of call, Tripoli.

Long before becoming the City of Discovery, Dundee was known throughout the world as Juteopolis.

In 1838 the first jute mill was opened and at its peak there were 150 jute firms in the city with the 282-foot Cox’s Stack in Lochee becoming a landmark for what became the largest jute works in the world.

Other large mills included the Coffin Mill and the Seafield Works.

In its heyday the city was the world centre for the manufacture of the fabric, with around 40,000 people dependant on the industry for their livelihoods.

The jute industry was hit by a series of booms and slumps in the 19th century, before slumping into decline in the 20th century.

By 1950, there were only 39 jute firms left out of a total of 150 at the industry’s height, with polypropylene being widely used as the backing for carpets at the expense of jute.