Michael Alexander meets members of pioneering Dundee project Foolish Optimism who have been engaged in a national conversation about the ‘scourge’ of mental health amongst young people – and now want to ‘puncture the silence’ further.

Leigh Addis knows all about the “stigma” of having mental health problems.

Moving from Bournemouth to Arbroath for a “fresh start” aged six after her OCD, depression and anxiety suffering mum tried to end her own life and was hospitalised, the now 26-year-old was – and still is – carer for her mum.

However, Leigh says the experiences of being a childhood carer have also taken their toll on her own mental health, and to this day she is often “silently screaming” inside.

“My mental health issues originally started when I was in primary school,” she said in an interview with The Courier.

“I started self-harming at quite a young age.

“Unfortunately I sort of fell through the system because I never showed any issues at school – it was all at home. I got really bullied from my mum. Her OCD was hair pulling.

“I went through all my teens trying to get by, trying to deal with my mum who has very severe mental health issues, to a point where when I turned 18, I kind of ran away from home and got introduced to drink and drugs. I needed to escape from her. I needed to escape from everything.”

Leigh moved north to study drama at Aberdeen College. It was there and while working in a “clique” care home in the city, however, that she “completely melted”.

“Unfortunately that affected my mental health too,” she said, “and I decided to come home because my mum was getting worse.

“I got hospitalised at the age of 20/21 due to trying to end my own life. Things were very difficult.

“I couldn’t cope, couldn’t handle anything. I was still waiting for my appointment to get seen by my psychiatrist. Things just got completely and utterly worse to be honest.

“Unfortunately I was in hospital for over six weeks and got thrown out of hospital, becoming homeless, eventually getting supported accommodation.”

Leigh was diagnosed with anxiety and borderline personality disorder (BPD).

But she prefers to use the American phrase ‘emotional intensity disorder’ because it’s “easier to understand” and less stigmatic.

“If I use the phrase borderline personality disorder people think I’ve got two different sides to my head or five personalities,” she said.

“Unfortunately that’s the stigma against BPD because everyone automatically thinks – ‘oh what side are you today?’ Or ‘who are you?’ I’ve not got multiple personalities.

“But most of it unfortunately has led on from trauma as a child with how my mum was and still is. And she’s not getting any better.”

Leigh says her main issue in life has been a feeling that she “never fitted in” or “didn’t belong”.

It was only when she got involved in promoting a ground-breaking mental health film and national roadshow launched in Dundee last year, however, that she realised she was not alone with so many other young people around the country experiencing similar issues.

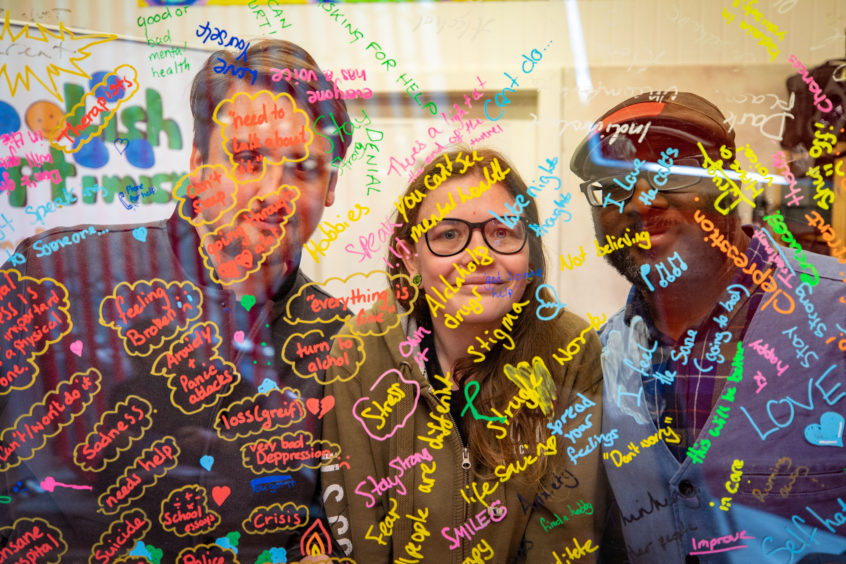

The project, titled Foolish Optimism, told the story of three mental health sufferers and explored mental health triggers, stigma, seeking help and coping mechanisms.

Initiated by young people, and aiming to carry a message of hope, the project was brought to life by Dundee Hilltown-based arts, education and social care charity Front Lounge, who attracted funding from the Year of Young People National Lottery Fund and Life Changes Trust.

Leigh was part of a team that toured Scotland with the project to “change the conversation” around mental health and build trust about speaking out.

Now, with ambitions to work in the mental health field herself and as efforts are made to secure a legacy for the project, she feels resource-starved mental health services can only improve if the “big wigs” actually listen to those using the service.

She was encouraged by a meeting the project had with NHS Tayside officials on January 21, and her “ultimate dream” is for 16-25 year-olds to have their own mental health service.

Thirty-year-old Dundee man Marc Ferguson – another volunteer with Foolish Optimism – says young people generally do seem to find it easier to speak about mental health than older generations.

However, the former St Clements Primary and Lawside Academy pupil who grew up in Charleston, believes leaders need to be “more responsible” in thinking about the causes of mental health problems instead of viewing vulnerable people like drug addicts and homeless people as “scapegoats for the problems of society”.

Marc first experienced mental health issues when he was 25.

His last job was in the web industry which he left due to the “toxic” working environment and the impact it was having on his mental health. This coincided with a time when he was also experiencing bereavement and relationship problems.

At its worst he was having three or four major panic attacks in a week. The physical sensation was chest pain and shortness of breath.

However, it took around three years for mental health issues to be diagnosed amid lingering deep-rooted introspection and self-doubt, and he is now on medication.

“The thing that shocked me about that when reflecting – looking back on it – is that I thought I had some idea of what it would be like to experience something like that,” he said.

“But I didn’t. Once it happened to me, I was one of these people who thought their experiences were not the same as anyone else, that I was alone and would not be able to explain it to anyone.

“As a result of doing Foolish Optimism I’ve found at least three people who’ve had almost identical experiences in the way that mental health problems present itself.

“There were different situations leading up to it but it was similar in terms of the presentation of the symptoms and the struggles.”

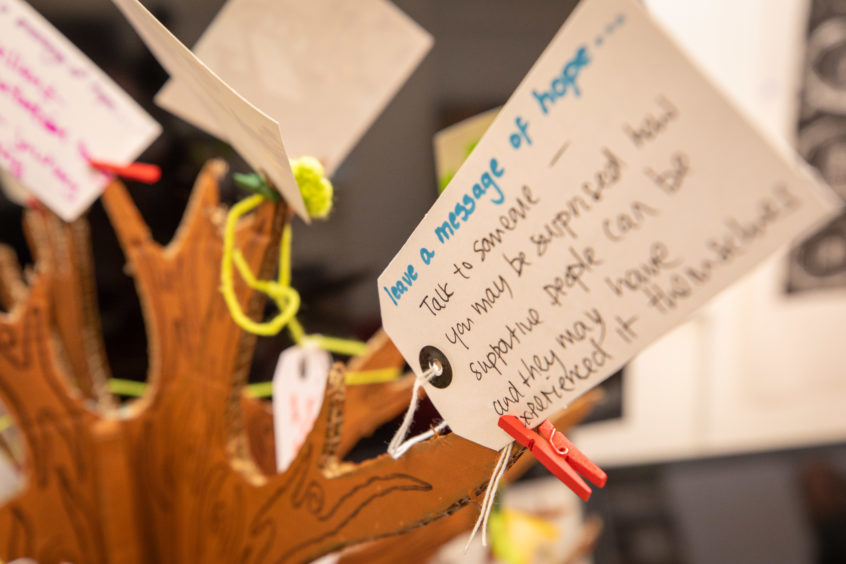

Putting the success of the Foolish Optimism tour down to conversations happening on a “level playing field” amongst peers, Marc said recurring themes included isolation and stigma.

“There is some unquantifiable genetic element that can explain peoples’ predisposition to mental health,” he said.

“But the majority of it is your environment and in order to change that in any meaningful way – a specific type of awareness is needed that these are mental health problems and this is where they might come from. How do we change behaviour to make it less likely that they manifest themselves in people you care about?

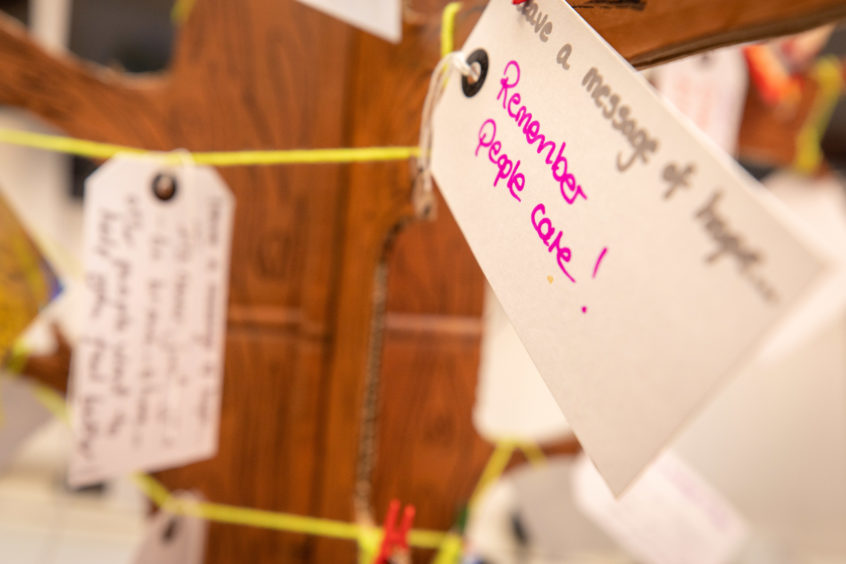

“For all of our ambitions of what we want to do we shouldn’t take away from what we’ve already done to demonstrate to a bunch of people that essentially they are not alone.

“We have seen the progress that people get from that recognition.

If all we did was continue doing what we are doing, the impact would be massive on its own.

“We shouldn’t lose sight of that.”

Front Lounge project director Chika Inatimi, who helped facilitate the project after being approached by several Dundee young people in August 2017, says society as a whole needs to take the scourge of mental health more seriously and stop “dismissing” the views of young people simply because of their age.

He said Foolish Optimism was really a “conversation about hope” that strived to “puncture the silence” of mental health and find solutions amid the challenges and pressures of the modern world.

“Hope is a very big word,” said Chika.

“Where our communities are more hope filled, then it’s more likely that even if there are problems, it’s more likely that solutions will be found.

“Hope is about future, hope is about possibility, hope is about tomorrow being better than today.

“A life without hope – what is that? That is despair and that is the very worst aspect of mental health.

“We met people who have tried to kill themselves or parents of people who have passed away – kids who’ve killed themselves – and it’s just a tragedy.

“Just the idea of a child killing themselves because they’ve lost hope – what does that say about us as a society? Seriously?

“One of the biggest complaints we had on this tour was that young people hadn’t been listened to, or had raised concerns and were dismissed.

“As adults we are going to have to be less dismissive of young people.

“At its heart we have to learn to listen right across the board then we can start fixing.”

Chika said the biggest initial surprise for him on the 25-stop roadshow was how common the issues were across urban and rural environments – and crucially it was childhood experiences that often “set the platform” for mental health problems in adulthood.

Some of the more horrific stories they heard were from children who would talk about bullying or experiences at home which rendered them just unable to function on a day to day basis. Those were very hard to listen to but also incredibly common, he said.

The project has ambitions to carry on engaging and to secure a resource base or ‘safe space’ where ideas can be piloted. An excellent outcome already was the Speakeasy project – a resource for carers and parents developed in collaboration with NHS Tayside.

What they really want to do, however, was find long term solutions through a participatory design process – to map out local solutions over a period of time.

This would identify key themes including isolation, trauma and education and think about specific relevant solutions.

Significantly, half of the project’s working group last year came from a care background – again often linked directly with mental health issues – while the project has now been invited to submit a letter about the tour experience as part of a national care review.

“We have all these ideas buzzing about,” said Chika. “The key thing is finding the right partners and resources – money included – so we can carry on. The NHS has been incredibly supportive of this project but I imagine that some of our conversations we’ll need to push with them.

“It feels very much like we’ve just started.”

Dr Drew Walker, director of public health with NHS Tayside said: “The Foolish Optimism film highlights the power of speaking openly about mental health.

“By sharing their experiences of mental health, the young people involved have created a valuable resource for opening up conversations and breaking down stigma surrounding mental health.

“They are passionate about identifying ways to make things better for other young people who may be experiencing similar issues and we would encourage everyone to take the time to watch the film.”

* If you are experiencing mental health problems or need urgent support, it is important to get help. Talk to someone you trust or phone Breathing Space on 0800 838587 or the Samaritans on 116 123.