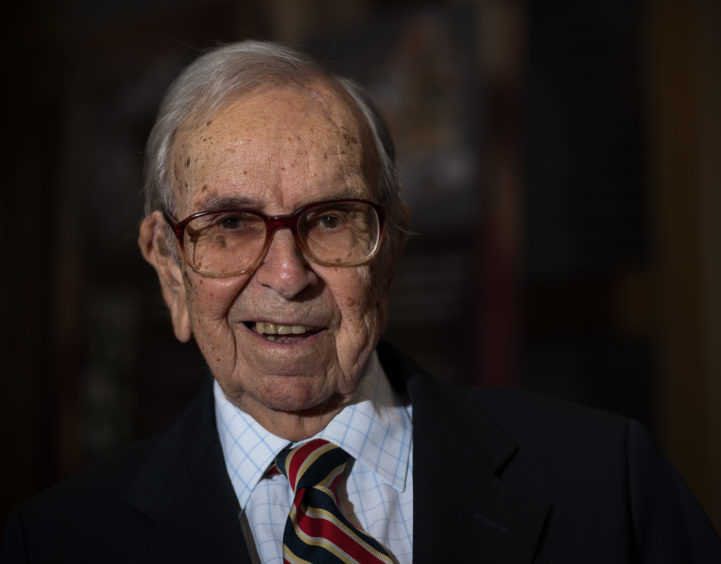

Michael Alexander meets former Jewish-German refugee Henry Wuga who escaped the Holocaust on the Kindertransport only to be wrongly accused of being a spy after evacuation to Perthshire during the Second World War.

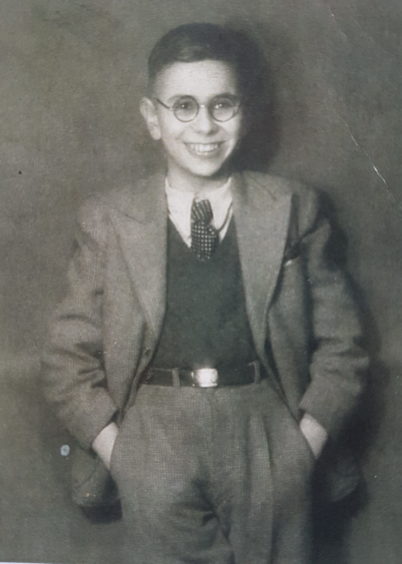

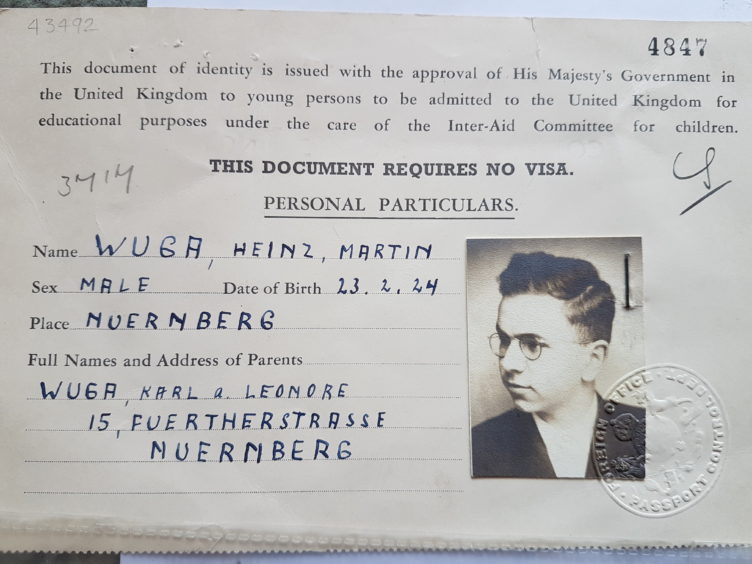

As a youngster growing up in the German town of Nuremberg where the Nazis held their notorious pre-war propaganda rallies, Henry Wuga and his parents experienced anti-semitism “from the minute” Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933.

As a 10-year-old, Henry was expelled from school “just for being Jewish” and in 1935 he remembers how Hitler’s anti-Jewish Nuremberg laws attempted to crush Jewish businesses.

Then came the “horrible” Kristallnacht – the ‘Night of the Broken Glass’ – in November 1938 when Nazis smashed up Jewish homes, stores and synagogues.

An estimated 30,000 Jewish men were put in concentration camps for six weeks – a mere warm-up for what the Nazi regime had in store for millions more during the Holocaust that followed.

But as Henry, now 95, recalled how he “miraculously” escaped pre-war Germany on the Kindertransport – a rescue effort organised by World Jewish Relief (then The Central British Fund for German Jewry) to remove Jewish children facing Nazi persecution – he expressed concern that the politics of prejudice are on the rise in Britain and Europe again.

And he expressed “dismay” at the divisions being created by the Brexit debate at a time when hate crime in Scotland is on the rise.

“It’s terrible what’s going on right now – absolutely horrible,” he told The Courier as he attended a Scottish Parliament reception organised by the Anne Frank Trust.

“Present day politics – Brexit doesn’t help –has split the country. For God’s sake I’m horrified! People begin to hate each other. This is how it starts. It’s quite worrying really. Being a refugee who found a home here, I feel Scottish. But I feel we should be part of Europe. I am certainly a Remainer. I can understand the leavers’ point of view. But this brand of anti-Europeanism – I think they are wrong. There is so much at stake.”

Born into a Jewish family of caterers in 1924, Henry was educated as an apprentice Commis Chef in Baden Baden in the Black Forest, aged 14.

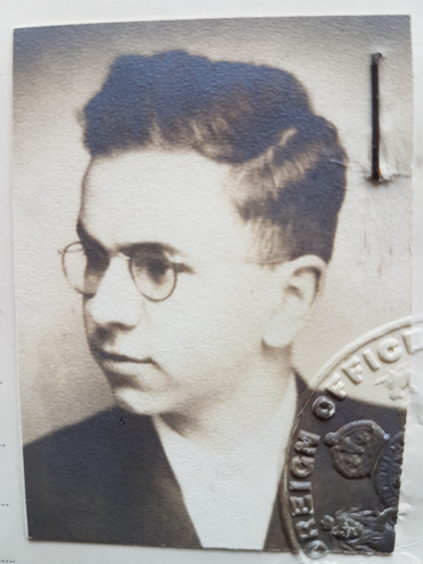

Before the outbreak of war in 1939, and as tensions rose, his parents found him a place on the Kindertransport child rescue effort from Nuremberg.

On a train crammed full of crying infants, he made the “awful journey” through The Netherlands and onto London, arriving at Liverpool Street Station on May 5, 1939.

There he met his ‘guarantor’ – a Jewish widow Etta Hurwich – and settled in Glasgow. He was lucky to find a warm and welcoming home.

However, his troubles began when war broke out and he was evacuated to Guildtown in Perthshire.

He had not been there long when he was arrested for “corresponding with the enemy” and wrongly accused of espionage.

“When we were evacuated I ended up in Guildtown,” he said.

“I went to school in Perth for four/five months. I had a very good time there. I learned fishing in the River Earn, worked on a farm. Everything went fine.

“But when war broke out I wondered ‘how can I communicate with my parents’?

“I had an uncle in Belgium, so I wrote to him in German, and he would send the letters to my father and mother in Nuremberg.

“But as the letters went back and forward, they were intercepted by the British censor. I was accused of corresponding with the enemy. They thought the letters contained a code.

“In 1938/39 we came here as refugees due to Nazi oppression. We were given the status Friendly Enemy Aliens Category C.

“But because these letters were captured by the censor, I was taken to the High Court in Edinburgh at the age of 16 and within half an hour I became a ‘Dangerous Enemy Alien Category A’ instead.”

Henry says that in hindsight he can understand why, after Dunkirk, the British authorities interned all Italians, Germans and Austrians resident in Britain. After all there was a war on!

The trouble was, most of the men arrested were perfectly innocent and because he was under 17, he could not be detained in a cell.

He spent time in various temporary holding centres and even a borstal in Glasgow – including a spell with German sailor prisoners – finally arriving at the notorious Warth Mills internment camp in Bury, Greater Manchester.

“There were 2000 of us in that abandoned old cotton mill with just 10 taps of water and 60 buckets,” he recalled. “We had a hessian sack stuffed with straw to sleep on, we were strip searched. It was horrendous. Very poor.”

It was a desperate situation for a boy of 16 separated from his family and accused of being a spy.

After a few weeks he was transferred to the Isle of Man where conditions were “better”.

However, it was here – he was later to learn through a modern day Freedom of Information request – that he was bunked up with an MI5 spy, intent on finding out the “truth” about him.

It was only a declaration of his innocence by MI5 that got him released from prison 10 months later.

On his release Henry went back to Glasgow and worked in several high-end restaurants as a chef de partie.

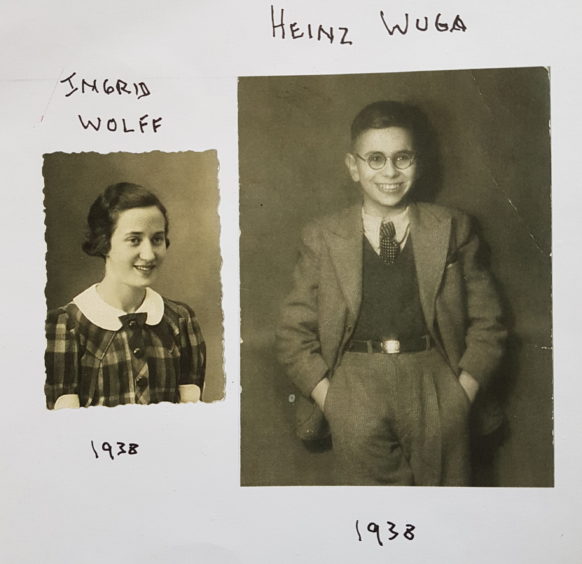

In December 1944 he married Ingrid Wolff who had also arrived in Britain on the Kindertransport.

He played an active role in German and Austrian refugee clubs and was eventually granted British citizenship.

In 1947 his Jewish mother, who survived the war after being hidden by a friendly Catholic family in Germany, arrived in Glasgow. Sadly his father had died of a heart attack during an air raid in 1943.

Henry went on to run his own renowned kosher catering business for the Jewish community in Glasgow.

In 1999, he was honoured with an MBE for Service to Sport for Disabled People, recognising his long association as a ski instructor for the British Limbless Ex-Service Men’s Association.

The couple still live in Glasgow where they enjoy a busy retirement with their two daughters and four grand-children.

However, despite the cost of war, and despite Ingrid losing four uncles and 12 cousins in Nazi concentration camps, he still manages to differentiate between the evil of Hitler’s Nazi war machine and the German people – including the Catholic family who saved his mother.

As well as visiting schools, camps and prisons, he has also been to the Jewish Museum in Berlin to talk to young Germans.

Henry Wuga has shared his story in more than 100 Scottish schools over the years, and at the Scottish Parliament this week, he was delighted to join pupils from Tayside high schools at a special reception to celebrate 10 years of education charity Anne Frank Scotland.

He also thanked the Scottish Government for its ongoing support.

Teenagers from Dundee’s Grove Academy, Morgan Academy, Harris Academy, St John’s R.C. High School, St Paul’s R.C. Academy, Baldragon Academy, Braeview Academy and Craigie High School attended the reception hosted by Scottish Parliament Presiding Officer Ken Macintosh along with representatives from Brechin High School, Forfar Academy and many other schools in Scotland.

The reception showcased the work of Anne Frank Ambassadors: young people the charity has empowered through its educational programmes to challenge prejudice and discrimination, and who continue to spread Anne Frank’s message of social justice and equality in their schools, local communities and online.

Megan Lumsden, 15, a fourth year pupil at St John’s High School in Dundee, told The Courier how the charity had allowed pupil delegates to visit the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam.

She said: “It’s important not to forget. It’s important to teach people from a young age – teaching them all the wrongs about what’s happened.”

Bronwen Terrani, 17, a sixth year pupil at St John’s with ambitions to be a biology teacher, added: “I started with the Anne Frank Trust when I was in second year. I’ve been doing it for four years now.

“Even with the amount of experiences we’ve gained from being a part of Anne Frank, I feel like we can even take it on with us to university and probably even beyond that when we do find a job.

“I feel it’s probably given us a different perspective on what’s going on.

“As a teacher, I can influence other children or even my own pupils one day about what’s happened in the past, what’s happened in the present and what might happen in the future about discrimination and stereotyping.

“I’m hoping I can pass on my experiences to future children.”

According to the Crown Office’s 2017-2018 report, racial crime remains the most commonly reported hate crime in Scotland and the number of reported incidents relating to disability has risen by 51%.

The reception included the Anne Frank Trust exhibition, Anne Frank: A History For Today.

Other speakers at the event included Robyn Lee – lead teacher for the Anne Frank Scotland programme at Harris Academy, Dundee, and former Anne Frank Ambassador – plus Anne Frank Ambassadors from Brechin High School.

Tim Robertson, Chief Executive of the Anne Frank Trust UK, said: “Learning about Anne Frank is sobering and uplifting.

“Her murder in the Holocaust at the age of 15 is, I think, what makes our young ambassadors take so seriously their role of standing up to hatred.

“And the way Anne turned her experience into her diary, loved by millions of readers across the globe, inspires young people to find their voices and speak out for truth.”

Dana, Anne Frank Ambassador from Brechin High School, said: “We have been very lucky to have the opportunity to be a part of Anne Frank Scotland.

“Anne’s positive outlook on life and focus on equality, despite everything she was facing is truly inspiring and incredible. It is vital that we never forget the harm that prejudice can do.”

Paula Fraser, Project Manager for Anne Frank Scotland, said: “I’m delighted that Anne Frank Scotland has the privilege of holding the reception at the Scottish Parliament, hosted by the Presiding Officer, the Rt Hon Ken Macintosh MSP.

“We’re excited to be celebrating 10 years of challenging prejudice and discrimination across Scotland: our Anne Frank Ambassadors never fail to inspire us in continuing Anne’s legacy for the next generation.”

The Rt Hon Ken Macintosh MSP, Presiding Officer of the Scottish Parliament and host for the reception, said: “Anne Frank Scotland is committed to empowering young people to challenge all forms of prejudice and discrimination, something which is as relevant now as it ever was.

“As we celebrate the Parliament’s 20th year, it is a chance for us to reflect on how far we have come as a society in that time, but also to perhaps think about the challenges which still face us and the intolerance which is still too common in our country.

“That is why the Anne Frank young ambassadors are so vital. These are the people who are using their voices to inspire change in all of us.”