It was the revolutionary project which marked a turning point in Scotland’s social history.

A hundred years ago building work started on the first council housing scheme in Scotland – the Logie estate in Dundee.

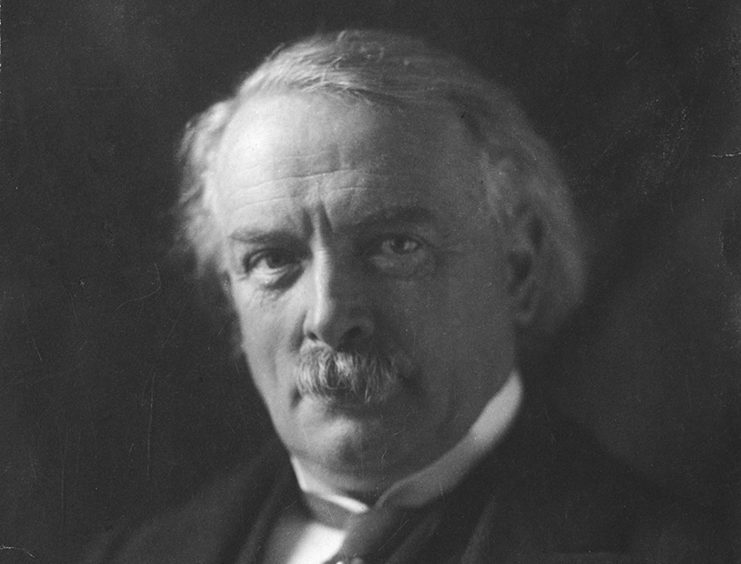

It followed a promise made by Prime Minister David Lloyd George during the First World War that the country would create “homes fit for heroes” when the conflict was over.

Logie was designed by renowned city architect James Thomson and would become the first housing estate in Europe to have a district heating system, a highly innovative project for its time.

The design of the houses also represented a major change for architecture in Scotland; the two-up, two-down design a sharp contrast to the tenements that dominated the area.

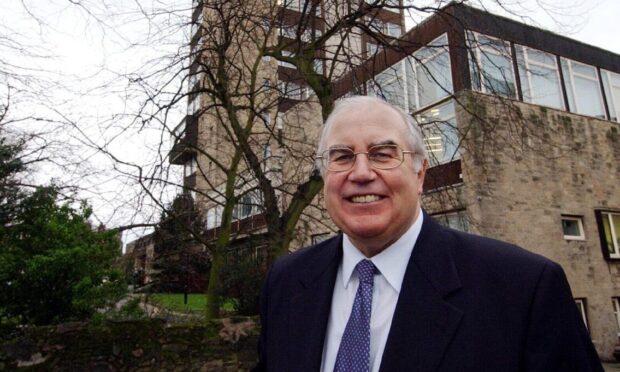

Historian Norman Watson said the new homes were regarded as necessary to address the city”s “dreadful housing” after a 1917 Royal Commission highlighted the “32,000 living in overcrowded conditions in Dundee”.

“Logie’s four-flat blocks, planned by James Thomson and centred on a tree-lined avenue, was a model that cleverly imitated upmarket villas and which departed from high-rise tenements and the fashionable ‘garden village’ workers cottages created as a solution in England,” he said.

“Ahead of his time, Thomson had provided Scotland’s first municipal housing estate and the first heated housing scheme in Britain.”

The Courier declared “Where Dundee Leads” when Logie was opened in 1920.

Today the spacious estate still attracts town planners from far and wide, while there is renewed interest in Thomson’s vision as a city engineer and architect.

The houses cost £230 each to build and the rent for a two-room home was one shilling and three pence, rising to one shilling and nine pence for three rooms.

Valuation rolls from 1920 give details of the jobs of the first tenants, who included an artist, railway clerk, telegraphist, soldier, jewellery salesman and commercial traveller.

The living conditions were a marked improvement on those found in a 1905 study of the city centre slums carried out by the Dundee Social Union.

Inspectors visited more than 6,000 properties and discovered appalling accommodation, which accounted for a huge range of diseases and probably contribted to the high levels of child mortality at the time.

Slum clearance and new building began on a national scale in the early part of the 20th Century.

In Dundee, 180 council houses in the Taybank scheme were completed in 1924, followed by 280 at Craigie by 1928.

Soon the city had one of the highest proportions of council tenants in Britain.

In the period between the First and Second World Wars, around 11,000 council houses were built in Dundee, using a diverse range of materials, including concrete, brick, wood and even metal from melted-down aeroplanes for prefabs.

Thousands more followed in the years after the Second World War including the city’s multi-storey blocks, which were built between 1961 and 1971.

Priority for ex-servicemen when estate opened

The end of the First World War in 1918 created a huge demand for working class housing in towns throughout Britain.

In 1919, parliament passed the ambitious Housing Act which promised government subsidies to help finance the construction of 500,000 houses within three years.

The 1919 Act – often known as the ‘Addison Act’ after its author, Dr Christopher Addison, the Minister of Health – made housing a national responsibility, and local authorities were given the task of developing new homes and rented accommodation where it was needed by working people.

A Dundee councillor, the Rev Walter Walsh and pioneering city engineer, James Thomson, had detailed plans ready when the Bill was passed and got the Logie Estate under way.

Thomson noted the Logie site’s close proximity to the city centre and deemed it suitable for high quality tenements or cottage type housing with “space in profusion for gardens and allotments”.

The Lord Provost Sir William Don conducted the opening ceremony in 1920 and Dundee’s Black Watch military band played.

The scheme included 250 maisonettes which were incorporated into a municipal heating system that supplied central heating and hot water to each house.

The coal boiler house that supplied the residential development also provided a public wash-house for the surrounding area.

This was the first scheme of its kind in Europe and the first lets were prioritised for ex-servicemen.

The district heating scheme was closed in the late 1970s and individual central heating was installed in each house.

Over time a large number of the properties have been sold off and are no longer under council housing stock.

The estate has survived to this day relatively unaltered and is said to project a strong sense of uniformity and community.