As V&A Dundee celebrates its first birthday, The Courier takes a look at the romance between Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

At Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s wedding in 1840 the cake weighed 300lbs, and huge crowds stood cheering outside the chapel.

Albert wore a British field marshal uniform, while Victoria stood resplendent in a dress of satin and lace, with a diamond necklace and sapphire brooch.

She carried an orange wreath – a symbol of fertility – and it took 12 bridesmaids to carry her train.

Their marriage has gone down in history as one of the most deeply-felt love matches of modern times, with the pair said to have shared a distinctly un-Victorian passion.

Most of their offspring married continental royalty, earning Victoria the epithet “the grandmother of Europe”.

Unfortunately, their legacy remains tinged with tragedy, as two decades of happiness were followed by four of heartbreak.

After Albert’s death aged 42, Victoria wore the black cloth of mourning for the rest of her reign.

The lives of Victoria and Albert enthralled the public past and present, and set a benchmark for regal romance.

Even by royal standards, Victoria’s upbringing was unusual. She lost her father before she could walk, and endured a “melancholy childhood” under the auspices of her viciously disciplinarian mother. Under the elaborate Kensington System, she was isolated from other children, strictly monitored at all times, and required to sleep at her mother’s bedside until becoming queen.

At birth, Victoria was only fifth in line for the throne – niece to the incumbent William IV, rather than daughter – but by the time of his death she had been heir presumptive for several years.

In 1837, just turned 18 and barely 5ft tall, she woke to find herself ruler of a quarter of the globe.

Albert was Victoria’s first cousin – a fact rarely emphasised by modern narratives – but scores extra romance points for being vastly below his wife’s social standing.

The pair had met once before – sparks had not flown – but the intervening years had been kind to the prince.

“He is extremely handsome,” wrote Victoria, “his eyes are large and blue, he has a beautiful nose, and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth… but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful.”

Five days later she grew tired of waiting and popped the question herself. About her wedding night, the rather giddy queen wrote in her diary: “I never spent such an evening! His excessive love and affection gave me feelings of heavenly love and happiness I never could hope to have felt before.”

Albert was similarly delighted – “I can only believe that Heaven has sent down an angel to me”.

The following 21 years now carry two distinct narratives. The traditional view holds that Albert supported his wife personally and professionally through desperately unhappy pregnancies.

In contrast to the austere Victorian stereotype, the queen could be deeply emotional and tempestuous, and the intelligent young consort was adept at calming his new bride.

Victoria hated child-bearing; modern observers suggest she suffered severe post-natal depression.

Repeated pregnancies exhausted her, and when duties fell by the wayside Albert invariably picked them up. He became her rock, steadying country and family when Victoria herself could not.

The revisionist view, championed by a major biography released last year, argues that a domineering Albert was only too happy to ferret away the affairs of state, and gaslighted his wife into believing she was weak.

Shortly after their wedding, he grumbled that he was “only the husband, and not the master in the house”, and quickly secured keys to the Queen’s cabinet boxes. He positioned himself as Victoria’s de facto private secretary and adopted a liberalising political agenda, as well as a plethora of public positions.

In 1855, Florence Nightingale visited Balmoral, to deliver a report on the Crimean War. Unable to keep up with the conversation, after 10 minutes Victoria called Albert in to take over, and Nightingale later described her as “the least self-reliant person” she had ever known.

Which of these views you adhere to will probably always be a matter of opinion, but Victoria herself was in little doubt. Her “dearest Albert” dominates her diaries, a figure of absolute devotion and love.

In 1861 Albert died, probably of typhoid, and Victoria’s world was shattered. In her own words she, “dropped on my knees in mute, distracted despair, unable to utter a word or shed a tear”.

She ordered that Albert’s rooms be left exactly as they were, with hot water and linen brought every morning.

She gained a great deal of weight through comfort eating, and for five years shunned all royal duties, leading to Republican whispers among her subjects.

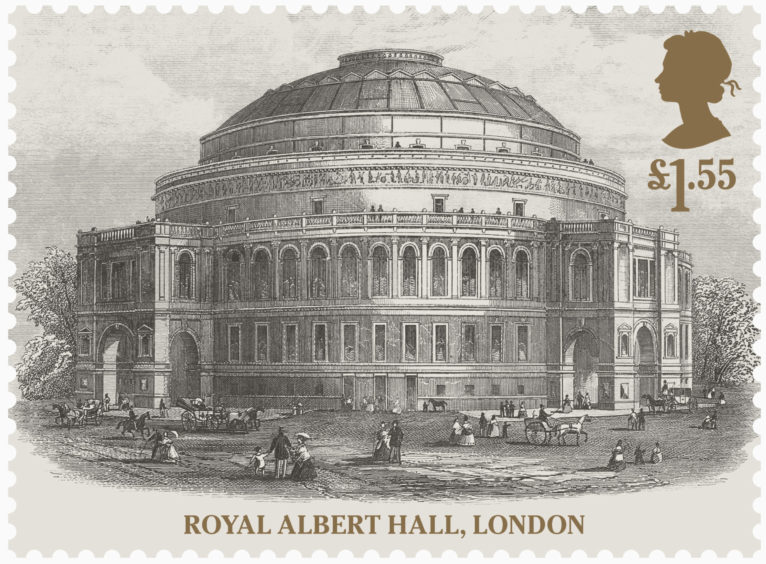

Monuments to Albert sprung up across the country, including the Royal Albert Hall, leading Charles Dickens to remark that he would need an “inaccessible cave” to escape them.

She never remarried, and on her death in 1901 was buried alongside Albert in the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore, with one of her husband’s dressing gowns and a plaster cast of his