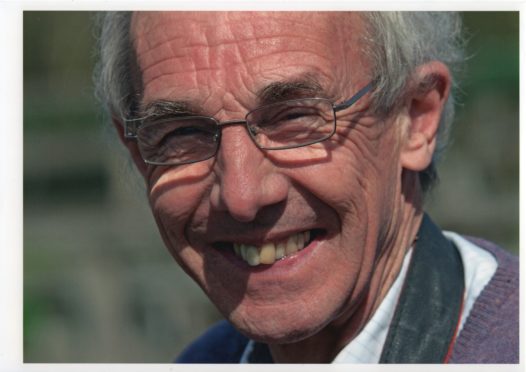

Tributes have been paid to a leading endocrinologist and naturalist who has died at his home in Fife after a short illness.

Gerald Lincoln, BSc, PhD, ScD and FRSE, who was born in Norfolk in April 1945, died at Puddledub in Fife on July 15 2020.

A considerable polymath, Mr Lincoln devoted his remarkable life to unravelling the mysteries of nature.

His father, a Norfolk tenant farmer, died when he was six and the family had to leave the farm.

His mother and her brother then bought a farm near Reepham, where he spent his childhood years running through the countryside and marvelling at the birds and especially the moths.

He became an adept poacher too, carrying toilet paper as an alibi when he ventured off the road and into the woods.

With his older brother Dennis, Mr Lincoln started trapping and recording moths, a project that won him the Prince Philip Award for Zoology and led to a place at Imperial College, London, studying zoology. It was at this time that he met his future wife, Caroline.

Roger Short, working at the veterinary school at Cambridge, had read about Mr Lincoln’s moth project in the newspapers and invited him to study the deer on the Isle of Rum for a PhD. His work led to a clear understanding of the way in which the red deer breeding cycle, including antler growth, is controlled by day length to ensure the hinds calve at the optimum time to benefit from spring grass.

It was while working from Rum he noticed that his beard growth increased whenever he anticipated leaving the island and going to see his girlfriend.

Beard growth reflects testosterone levels so in the true spirit of investigation he weighed his beard shavings daily to demonstrate the phenomenon. The results were subsequently published in a famously anonymous paper in Nature – a very rare distinction.

By measuring the frequency with which his rams hit their heads against the sides of the pens he created an index of ‘irritability’ and demonstrated that, counterintuitively, this increased as testosterone levels fell.

From this he identified a ‘male irritability syndrome’ pointing out that grumpiness in men coincides with the decline in testosterone with age; a theory that attracted widespread publicity.

Over a 40-year career, Mr Lincoln received numerous scientific awards and medals including the election to fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and appointment as Emeritus Professor of Biological Timing at Edinburgh University.

Throughout their time at Edinburgh, Mr Lincoln and his wife based themselves at Kirkton Cottages, Puddledub in Fife, transforming two farm cottages and the surrounding grass paddocks into what was to become a paradise of biodiversity and a nature reserve.

In retirement Gerald was able to devote himself to this work, constructing a sand martin colony which each year bred over 400 fledglings, attracting a breeding pair of mute swans to his ponds, and crucially recording moths all over Scotland.

Moths provide a means of measuring environmental change and Mr Lincoln came to see very clearly the gravity of the damage to our environment.

As he wrote: “The alarm bells have gone off – industrial farming and the encroachment of towns is trashing the countryside. Gone are the butterflies and the wild flowers – a crisis.”

He leaves his wife Caroline, two sons, Richard and Robbie, and a daughter, Rachel.