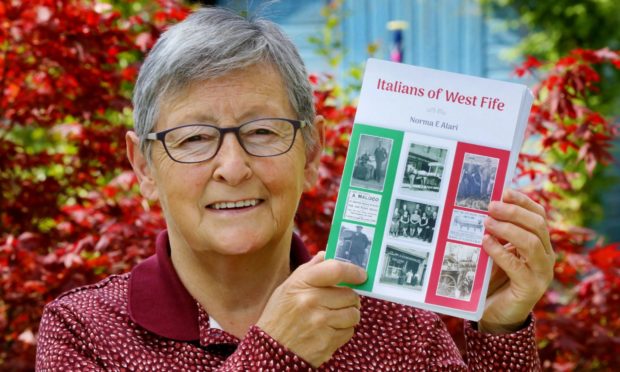

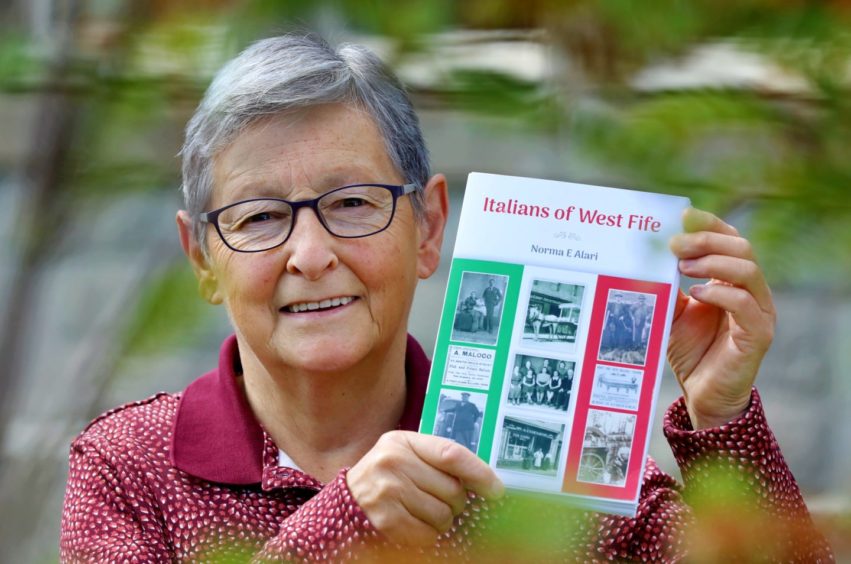

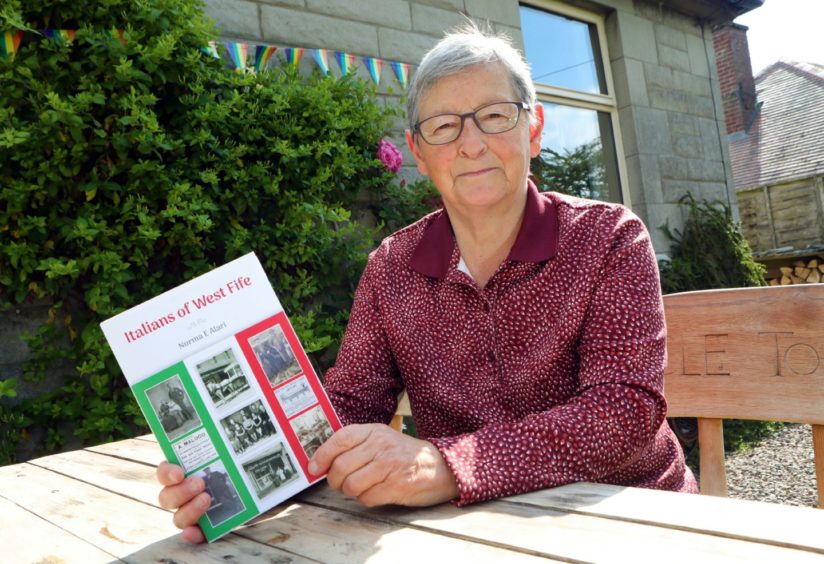

Michael Alexander speaks to retired Dunfermline nurse Norma Alari about the book she has written which explores the history of Italians, including her own family, who settled and established businesses in West Fife.

When Dunfermline-born Norma Alari took early retirement more than a decade ago after 37 years as a nurse, it gave her time to investigate her Italian roots.

With both sets of grandparents born in Tuscany and migrating to Scotland around 1902, her parents ran Alari’s fish and chip shop in Dunfermline for decades, and her aunt had her café next door to the chip shop too.

However, with even more time on her hands when the country went into lockdown during March 2020, the now 68-year-old was inspired to do something more substantial with the information she had collected by writing a book.

Book

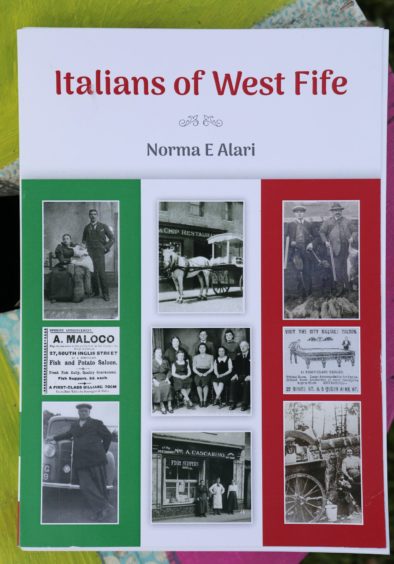

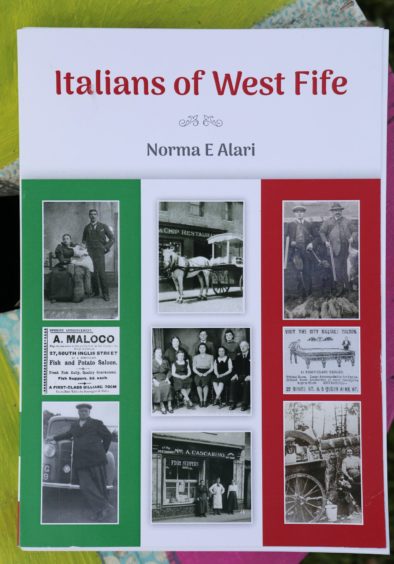

Sixteen months on and Norma is publishing the 130-page Italians of West Fife: Dunfermline, Cowdenbeath, Inverkeithing and Kelty – 1800’s – 1930’s.

“The book is about Italian migrants from the regions of Lazio, Tuscany and Emeila-Romagna having left from hillside villages of Atina, Casalattico, Barga and Borgotaro,” she says.

“I have written about at least 26 individuals who lived and worked in Fife – as well as other areas of Scotland.

“Information has been gathered from census, newspapers, oral history, Dean of Guild, assessment rolls and loads of academic papers and books and naturalisation case papers.

“The book runs to 130 pages and I think it will appeal to everyone who remembers their favourite chip shop and café and I hope too descendants of the folk written about.”

Fife-Italian heritage

A former pupil of St Margaret’s RC Primary and St Columba’s RC High School in Dunfermline, Norma, who now lives in Cupar, explained how records show that Italians have had a presence in Britain since Roman times and from the 17th century many skilled and semi-skilled artisans and craftsmen worked in towns and cities across the country.

However, from the late 19th century, as Italians experienced poverty and famine in their home country, Scotland saw an increase in Italian immigrants.

The 1871 census for Scotland recorded 268 Italians and by the 1911 census this figure had grown to 4,594.

Italians from the region of Tuscany settled (not exclusively) in large numbers in Glasgow and the west of Scotland with surnames such as Capanni, Giuliani, Gonnella, Marchi, Bertolini, Biagioni, Bechelli and Brucciani.

Italians from the region of Lazio settled in Edinburgh and the Lothians with surnames such as Valente, Caira, Magliocco, Di Ducca, D’Inverno, Divito, Taddei, Fusco and Mancini.

Italians from the region of Emilia-Romagna settled in the north east of Scotland with surnames such as Donati, Canale, Cura and Bertorelli.

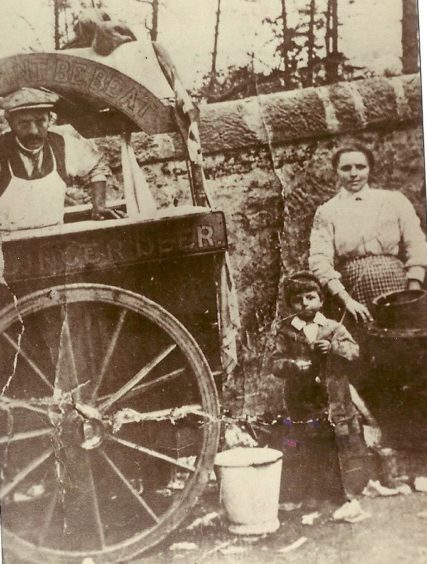

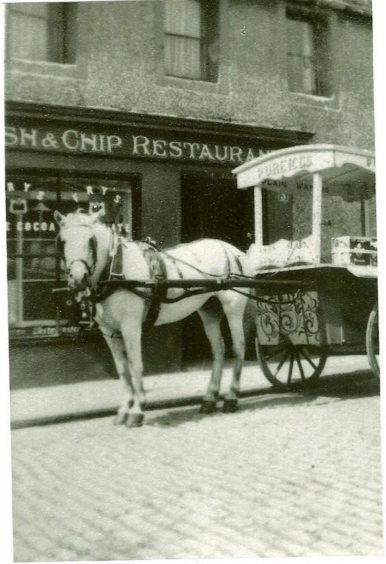

Tapping into census records, trade directories and valuation records, Norma learned that the main occupations recorded for Italians in Scotland were statue/figure makers, organ-grinders (musicians), confectioners, mosaic tile layers, bakers and hairdressers.

The earliest record of Italians in Fife is that for Antonio Staffiere, a confectioner in the 1881 census for Dunfermline.

However, it was not until the 1890s that other Italians were being recorded at other locations such as Auchterderran, Cowdenbeath, Lumphinnans, Markinch, Leven and Buckhaven.

By the 1920s, many Italian immigrants had created successful businesses.

Some ran ice-cream parlours and cafes, and they sent for their families to join them in Scotland.

Alari family history

Growing up in Dunfermline, Norma said many of the stories from her own family were “conjecture”.

One story passed down was that her grandfather Amos Alari on her dad’s side worked in the potteries in Stoke on Trent when he was 13.

The more she researched, however, the more she learned.

Her research revealed that in 1911, Amos was registered at a café in South Street, Perth.

By 1916, her grandad’s name was included on the valuation records for what became her parents, Donald and Nora Alari’s chip shop in Dunfermline – a business which her older brother took over when their dad died, and which was only sold in 2016.

“Because they are shopkeepers you’’ve got valuation records, you’ve got the census, you’ve got trade directories where you got them listed, and council minutes where perhaps they’ve applied for a licence for registration for their shop,” she says.

“The other valuable resource is the Dean of Guild records.”

Challenges facing migrants

As she delved deeper, though, she also learned of some of the challenges that had to be overcome by those early migrants.

Firstly, there was the economic context of why many migrated from Italy in the first place.

“These are people predominantly from the hillsides -they are farming people,” she says.

“I’ve broached that a wee bit in the book – their history as tenant farmers and land taxes increasing after the Napoleonic wars.

“They were big families and couldn’t all manage to live off the land so it was common practice for the youngsters to move away with a trade. I think that’s probably how Amos Alari as part of a group when he was 13 years old, ended up in Stoke on Trent.”

When it comes to why Italian-Scottish family history wasn’t always celebrated when she was younger, she puts this down to a number of reasons.

Society was “very Anglicised” by that time, she says. With Italians being Catholic, many families kept a relatively low profile with an undercurrent of persecution in Scottish society.

The other aspect that “kaiboshed” a lot of culture at that time was the Second World War.

When Italy became an ally of Germany and Italian leader Benito Mussolini declared war on Britain and France in June 1940, Italian immigrant men over the age of 16 were declared “enemy aliens”.

Over 4,000 Italians were arrested and many were shipped to internment camps on the Isle of Man. Others were transported to Canada or Australia.

There were anti-Italian riots in cities including Edinburgh and Glasgow. Italian businesses were attacked.

Internment camps

Norma isn’t aware of members of her family being sent to internment camps.

“During World War Two quite a few Italian shop keepers in Dunfermline put notices in their shop windows stating they were British citizens,” she says.

“There were quite a few Italian men who naturalised just before the war – my grandfather Amos Alari being one of them.”

However, other members of the extended family were treated as “aliens”.

“On my mum’s side in Kilmarnock, because Kilmarnock was a protected area because of a munitions factory, that whole family there were moved because they were considered aliens and punted out to Glasgow.

“I’ve got my grandmother’s ‘alien’ documents where she had to report to the police and have her wee documents stamped.

“When they went back to the family house in Kilmarnock (at the end of the war), a lot of my grandmother’s clothes and pottery had been taken by the people who had been put in the house. She had to clean the house.

“I had an uncle in Irvine who was arrested and sent to the jail in Irvine. But he never got interned.

“Other than that, for Dunfermline, there’s Divito in Crossgates, the ice cream people. Their old man was taken away and interned.”

Learning curve about Fife Italians

Growing up in Dunfermline, Norma says she could probably list four Italian families.

But in the process of research, which took her to libraries and even the National Archives at Kew in London, she was surprised to learn there was probably about 100 Italians on and off who have been connected to Dunfermline, and likewise, Cowdenbeath, Kelty, Lochgelly, Markinch during that period.

To become a British citizen around 1915, applicants had to have so many householders give a reference.

Through her research and speaking to descendants, she’s managed to list some of those people.

Dunfermline Italians explored in the book include Antonio Staffiere, Giovanni Segalini, Carlo Felice Rebori, Carlo Felice, Galione, Giuliani, Dominico Berturelli, Maloco, Arcangelo Tartaglia, Ernesto Boni, Fortunato Vernolini, Raffaello D’Inverno, Motroni, Francesco Capanni, Angeloantonio Cascarino, Taddei, Fusco, Catignani, Amos Alari, Aquilino Rossetti, Enrico Casci and Giovanni Leonardi.

Work ethic

What they all had in common was they were hard working people who had a good business sense.

It was a work ethic she was conscious of growing up.

“We hardly saw my dad when we were young,” she recalls.

“He was away to the shop early morning, to get everything prepared. We saw him at lunchtime and then the shop opened at 3 or 4 in the afternoon until 11 at night. They did work. It was long anti-social hours. They worked seven days a week.”

Norma is also grateful for the help and assistance from librarians and archivists – past and present – and to all who took the time to speak about their families.

How to get hold of Norma’s book

Norma, (who can be contacted via nalari@btinternet.com), hopes to have to have the book published by the “end of June/start of July”.

Dunfermline Library have agreed to do a launch. She’s approached Waterstones in Dunfermline too and expects interest to develop “by word of mouth”.