Michael Alexander speaks to former school teacher turned author Donald S Murray about his lifelong understanding of lighthouses and how this inspired his new book exploring their history and light keepers.

Since the earliest of these hardy structures were raised, lighthouses have been a lifeline for seafarers at the mercy of treacherous weather and uncertain navigation.

From ancient beacons to the work of the Stevensons and the Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB), and from wartime strife to automation and preservation, lighthouses stand as a testament to Scotland’s innate connection to the sea.

But what about those lesser known dramatic stories such as the day the light house keeper on the Isle of May saw debris float past from the infamous Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879?

What about the day the keepers at Dubh Artach in the Inner Hebrides were taken aback to see a bloated elephant and two mules in the water, assumed to be circus animals lost while being transported to America?

Or what about the tragedy at Fair Isle North during the Second World War when the 22-year-old wife of the light keeper was killed by German machine gun fire as she stood at her pantry window?

Within weeks, the Luftwaffe returned to hit the main block of the lighthouse, killing the principal light keeper’s wife and child…

‘Haunted’ by lighthouses

Donald S Murray gives a wry smile when he says that lighthouses have been haunting him all his life.

Growing up under the gleam of the Butt of Lewis lighthouse on the Isle of Lewis, and surrounded by islanders whose communities are intrinsically linked to the sea, he’s always had a deep understanding of their stoic presence on the edge of the landscape.

However, while researching his new book For the Safety of All: A Story of Scotland’s Lighthouses, Donald has also learned considerably more about the history, storytelling and the voices of the light keepers who before automation, ensured the lights stayed on.

“Growing up on Lewis, I knew men who worked for lighthouses,” says Donald in an interview from his home on Shetland, where he lives in sight of the Bressay lighthouse.

“There were school pupils I went with who were the children of keepers. I’d go down to the family croft and I would see the Butt of Lewis lighthouse which in those days shone across the village where I stayed.

“In Stornoway when I grew up it was full of fishermen, so you’d hear them talk about lighthouses and the stories attached to lighthouses. My mother’s people came from Tiree which is near the Skerryvore lighthouse. In a sense it’s always been there with me.

“But there was tragedy too. The Flannan Isles lighthouse is the most well known where three men went missing (before Christmas 1900).

“In my primary school days, one of the head teachers was related and used to tell the story. On the Monarch Islands, two keepers were killed too.”

Teacher turned author

Born and raised in Ness in the Isle of Lewis, Donald Murray, now 65, spent his teenage years at the Nicolson Institute in Stornoway, before studying at Glasgow University in the 1980s.

After receiving an MA (Joint Hons) in English and Scottish Literature, the Gaelic speaker went on to gain a Diploma in Education and a Secondary Teaching Qualification.

After 30 years as an English teacher, Donald became a full-time writer in 2012. He has written 11 books and published countless essays, columns, short stories, and poems. His work has received widespread critical acclaim.

Before Covid-19, he was commissioned by Historic Environment Scotland (HES) in partnership with the NLB to write the book as part of Scotland’s Year of Coasts and Waters 2021.

With over 100 of Scotland’s lighthouses now listed buildings, the lighthouse is now one of many maritime resources which act ‘for the safety of all’.

Since 1998, all of Scotland’s lighthouses have been fully automated and remotely monitored from the NLB’s headquarters in Edinburgh. They are maintained by technicians.

Yet people are still drawn to stories of the solitary keeper, the beauty of the lens of the lamp and the calm reassurance of a flashing light on a distant shore.

Perhaps there’s an irony that many people, through lockdown, had a taste of what the solitude of a lighthouse keeper may have felt like – albeit without having to keep an eye out for ships.

Early lockdown

To write the book, though, Donald effectively went into lockdown before anyone else.

“I knew for a variety of reasons that working at home in Shetland was not the best location for writing the book because I would have to go to places like Fraserburgh, Arbroath, Edinburgh and other locations – and I couldn’t really do that from Shetland,” he says.

“A friend of mine offered me his cottage in Lochcarron in the West Highlands. I worked from his house while he was away for the whole winter diving.

“That permitted me to travel to places like Skye, Gairloch and Arbroath.

“When lockdown came, in a sense it prohibited me from visiting as many lighthouses as I’d have liked. But it did give me time to finish off the book.”

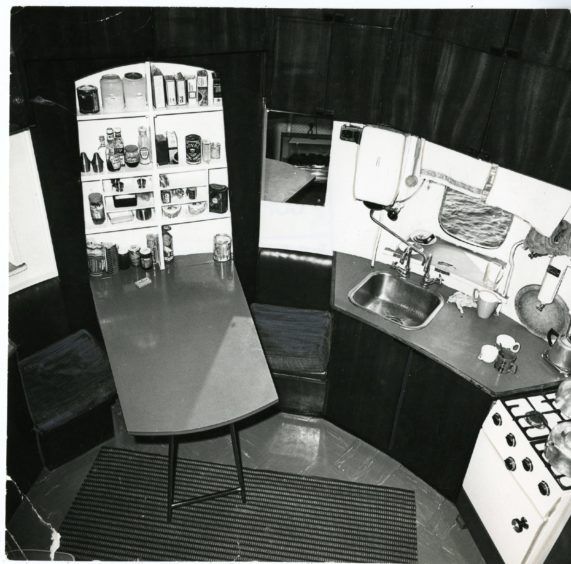

During his research, Donald learned more about how lighthouse keepers had to draw on their own resources to keep themselves on the go.

A lot of them had craft skills they used in their time off. He met a former keeper from Orkney who was very good at making ships in a bottle.

“There were also musicians who practiced their fiddles in Shetland and Gaelic speakers who wrote songs.

Others were nature observers who spotted birds and whales.

Traits of a good lighthouse keeper?

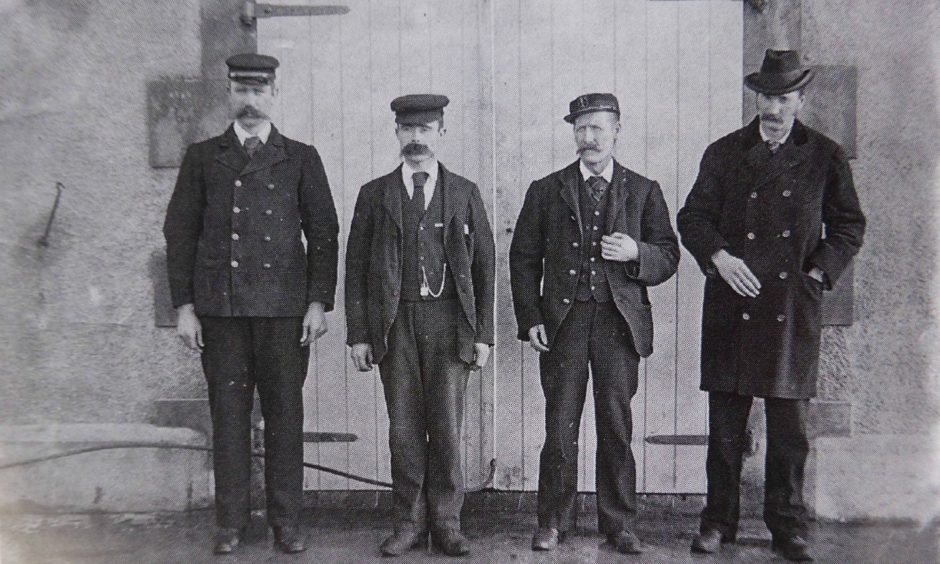

Donald says the best lighthouse keepers were self-assured, relatively private people with an independent spirit. They also needed a real sense of duty.

It’s no coincidence that a lot of the original light keepers came from isolated communities in the Western and Northern Isles.

“I think they thought they were the best for the job,” he says.

“That changed as time went on with an increasing number of town and city people. For the first few hundred years it was people used to a solitary life.”

However, Donald was also struck by the heroism of lighthouse keepers. While strictly speaking they weren’t meant to get involved in rescues, they consistently broke the rules.

“Gairloch was one example,” he says, “and here in Shetland in the Pentland Skerries, there was a guy who helped to save men and women when an East German ship went down.

“I think we always think of them as remote and in a way their job was slightly monolithic – not getting involved. But quite frequently they did. They helped save lives.”

Dundee and Fife links

It was Dundee and Fife-educated Perth Burghs MP George Dempster who established the Northern Lighthouse Board in 1786.

It’s apt then that the book includes a sizeable section on the Isle of May, in the Firth of Forth, and also on the Bell Rock lighthouse off Angus – the world’s oldest surviving sea-washed lighthouse, built between 1807 and 1810 by Robert Stevenson.

“I have a lot on the Isle of May,” says Donald.

“Beacons there go way back. Benedictine monks lit that way back in the 6th/7th century. I don’t think that was unusual.

“But a thing that puzzled me – I kept uncovering evidence that throughout Scotland they regularly used to light beacons to help people.

“On the Macleod crest of Lewis they’ve got a bonfire on the crest. The MacAskill family on Skye also had this bonfire on their crest.

“These things went on long before any records were there, but we know of the Isle of May one. We know there were monks there from time immemorial.

“Bell Rock itself is a wonderful story, and even how wonderful it stands up today. One of the pictures I’ve got in the book is the very base of Bell Rock.

And what is really quite extraordinary about it – considering it was erected in 1811 – is it’s immaculate. It’s fantastic.”

Less successful, however, was the North Carr off Fife Ness, where countless ships wrecked over the centuries.

“That was Stevenson’s one failure in a way – it was swept away three times,” says Donald of Stevenson’s attempts to build a North Carr beacon.

An alternative pyramidal structure of cast iron columns with a ball on top was completed in 1821, later being joined by a lightship.

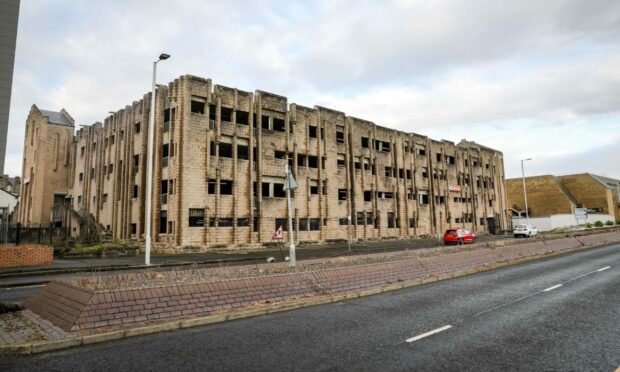

This was replaced by a lighted buoy in 1975 at the same time as a lighthouse was built at Fife Ness. However, the North Carr lightship – now berthed in Dundee docks – was not without tragedy itself.

When she broke adrift from her moorings at Fife Ness during a storm on December 8, 1959, all eight crew members of the Broughty Ferry lifeboat died while trying to rescue her.

* For the Safety Of All: A Story of Scotland’s Lighthouses, by Donald S Murray, will be available in bookstores from July 29.