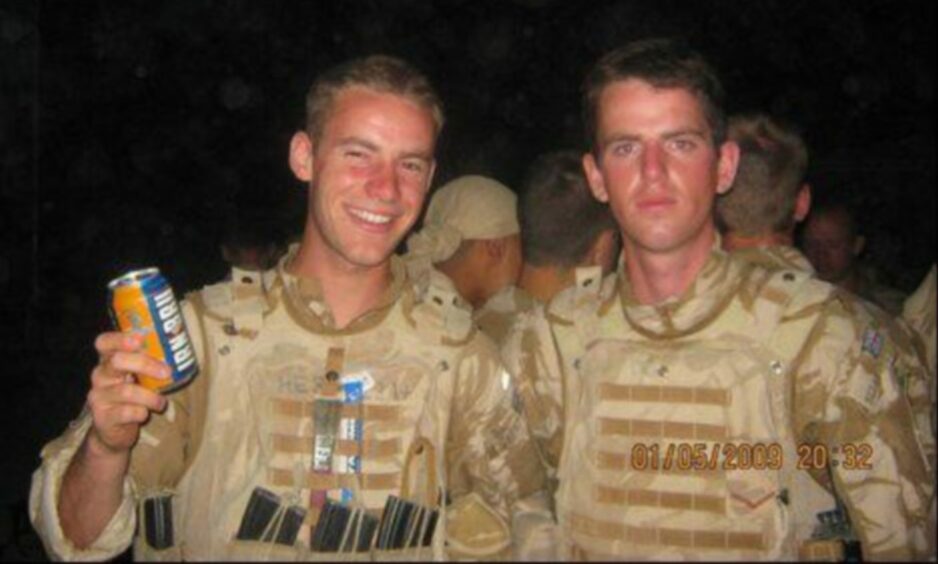

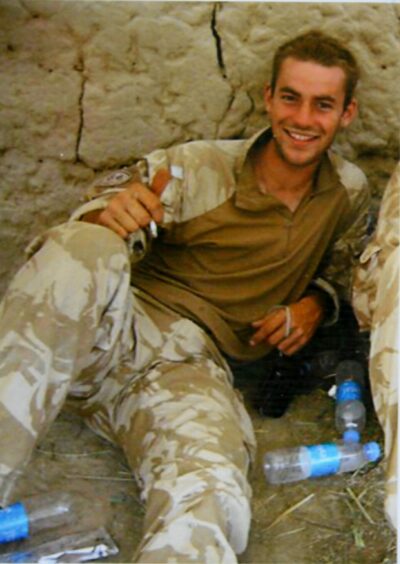

Michael Alexander speaks to former Black Watch soldier James Forrester about fighting the Taliban and why, despite the tragic loss of mates, he believes the British Army made a positive difference in Afghanistan.

Immersed in a world of rocket propelled grenades (RPGs) and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), Fife soldier James Forrester was only 20-years-old when he discovered the reality of being pinned down for hours under heavy fire where every moment could be your last.

The Black Watch squaddie from Methil served with the Royal Regiment of Scotland when his unit – Two Platoon, Alpha Company – was posted to Afghanistan in March 2009.

After intense training, his platoon quickly found itself in the thick of combat against the Taliban in the baking heat of Helmand.

In what became known as the British Army’s bloodiest summer of the war, they experienced the stresses of colleagues being blown apart or badly injured in heavy fire fights.

In one incident, he and his friend Aaron Black from Blairgowrie were standing next to a friend Robert McLaren, from Mull, just minutes before he was obliterated by a Taliban mine.

In another, Aaron was watching from a rooftop when Sergeant Stuart Millar, of Inverness, and Private Kevin Elliott, of Dundee, were wiped out by an RPG.

Colleagues had to struggle over rough ground to recover their remains on stretchers.

Back at Kandahar Airfield a few days later, James and two other Lance Corporals had the grim task of going through their blood splattered gear to separate personal/issued kit and strip out the ammunition so it could be accounted for.

A total of 100 British troops were killed in 2009 and many more wounded. But even when troops returned home, the death toll rose.

In 2011, while back on tour in Afghanistan, James heard from his mum that friend and former squaddie colleague Aaron Black had committed suicide at home in Blairgowrie, aged just 22, suffering PTSD.

Old emotions

James, now 32, admits that the recent scenes of western withdrawal from Afghanistan have “dragged up a lot of old emotions”.

However, speaking to The Courier from his home in Methil, and despite the traumas of 2009, the local factory worker, who left the army nine years ago after seven years, does not accept that the 20 years of military occupation launched after 9/11 was a waste of time.

“It’s a difficult question, but I’d never say it was a waste of time as it would soil some of the memories of some of the guys,” he says.

“The positives me and a few guys have said is hopefully with the taste of freedom we’ve given quite a lot of the Afghans, is that maybe they won’t accept the Taliban’s sh*t this time around.

“I would say military wise, the Taliban were beaten years ago. But the negatives are all they did was go away and hide and regroup and rebuild and then they’ve just waited for us leaving.

“Don’t get me wrong – some of the Afghan Army and that were good. But the vast majority were protected by the umbrella of the US Air Force, and as soon as that was taken away, they would not be interested in fighting either. That’s the way we look at it.”

War on Terror

The 20th anniversary of the 9/11 terror attacks, and withdrawal of western military, brings full circle the US-led War on Terror and the subsequent invasion of Afghanistan which led to the deaths of more than 3,500 coalition troops including around 2,500 US military since 2001.

Some 453 British service personnel were amongst those killed between 2001 and the departure of Britain’s combat troops in 2014, with around 2600 British soldiers wounded.

The number of soldiers who suffered psychological injuries remains unknown, as does the number of Afghan civilian casualties.

Yet when James thinks of his time in Afghanistan, he doesn’t think of it as being part of the war on terror.

While he knew their presence stemmed from the actions of al Qaeda, the reality on the ground was engagement with the Taliban or destroying the narcotics factories of local drug lords.

Memories of 9/11

James was 12-years-old and a first year pupil at St Andrew’s RC High School in Kirkcaldy on the day of 9/11.

He remembers coming home from school and standing in front of the TV thinking “bloody hell”.

By the time he joined the army aged 16 on September 2, 2005, however, he had started gaining further insight into the Middle East.

His uncle, who was a sergeant major in the Black Watch, was part of the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

He kept a book of Iraqi souvenirs, which James used to look at, and it was his uncle, when he was posted to the Kirkcaldy armed services careers office, who encouraged him to join the Black Watch.

James says that as soon as training began, it focussed on Afghanistan and Iraq. However, it wasn’t until he joined the battalion in 2007, and was more or less told they’d be in Afghan within two years, that he became really interested.

Afghan tours

James did two tours of Afghanistan – Operation Herrick 10 in the summer of 2009 as part of ISAF (International Security Assistance Force), and a winter tour in 2011/12. It was the first tour, however, that turned into a bloodbath.

“A lot of our training and stuff was focussed on de-escalation,” he recalls.

“We went out there with the full intention of Northern Ireland-style standing operating procedures like hearts and minds, don’t piss off the locals. If we are getting in contact, let’s try and not drop bombs.

“The Black Watch has a really good reputation of being proper professionals – getting the job done right. Unbeknown to us it would be the year that IEDs went up like 700%.

“The Taliban had obviously been beat tactically and had to resort to something to try and even the playing field a bit. When we were out there, we did try the peace keeping. We really did. But they just didn’t allow it. We could only do it so much before we just kept getting hit.”

James says he never got to the point his friend Aaron Black reached where he considered suicide.

However, a lot of Afghanistan veterans he keeps in touch with say “there’s always a small part of you that’s been left there”, and that’s certainly how he feels –admitting that he thinks about what happened in 2009 just about every day.

By the time he returned to Afghanistan in 2011/12, things had improved.

He remembers “kids and women going about doing what they wanted” – in stark contrast to his first tour when he saw an Afghan woman get beaten by a man simply for being waved at by a soldier.

Based at Britain’s furthest south patrol base in Nad Ali, they only got shot at once during that second tour.

Within a week of handing a patrol base over to the Afghan Army, however, the home trained army were “getting smashed” by the Taliban.

“It was at that point I was like, ken, these folk are just waiting for us to leave,” he says. “That’s when I realised this country’s going to go to hell when we leave it. You could ask me 10 years ago what was going to happen in Afghan and I could have told you exactly what’s happened in the last month was how it would be.”

Making a difference

James like to think the Black Watch made a positive difference.

However, he also realises the majority of the local population simply wanted a peaceful life – whoever was in power.

One conversation that sticks in his mind relates to the second phase of Operation Panther’s Claw – a British-led operation in Helmand Province that aimed to secure various canal and river crossings to establish a permanent ISAF presence in the area. He remembers asking an older Afghan man: “how do you feel about ISAF being here?”

The man replied ‘if you come here, whether you want to or not, you bring violence’.

“Any Afghan you spoke to, they just said they wanted a peaceful life,” recalls James.

“Wherever we went, we would bring the Taliban. But if we didn’t bother going into an area, while the locals might hate the Taliban, at least they wouldn’t have the fighting. That stuck in my mind a wee bit.

“They would say they were happy for us to be there. But I can guarantee that as soon as we left and the Taliban walked back in, they’d say ‘we’re glad that ISAF’s away and happy you’re here’. They just wanted to be left alone.”

It’s a view shared by Aaron Black’s mum June, who also likes to think that her son and his Black Watch colleagues made a positive difference in Afghanistan, before he took his own life.

“Whether Aaron or not believed he was there for the greater good, to help the Afghan people, I don’t know,” she says.

“I can only imagine Aaron believed at 20, having gone through training, that they were going to help rebuild the country.

“I just wish Aaron was here to tell you what he thought for himself.”