Michael Alexander speaks to Ludovic Lindsay whose painstaking restoration of remarkable family photographs mean a chronicle featuring the forebears of the Lindsays of Balcarres in Fife is available for the first time.

There’s a saying that you die twice – once when you stop breathing and the second, a bit later on, when somebody mentions your name for the last time.

It’s an analogy that could apply to every family with many names from the past being resurrected in recent years thanks to the growth of online genealogy.

London-born documentary producer Ludovic Lindsay was in the fortunate position that his family tree, descended from the Earls of Crawford, was already well documented.

The aristocratic family, which traces its roots back more than 1000 years to the time of Charlemagne, almost lost everything after siding with the Stuarts during the Jacobite rising of 1715.

Fortunate marriages, colonial endeavours and industry enabled them to create a new fortune and reclaim their position as the premier Earls of Scotland.

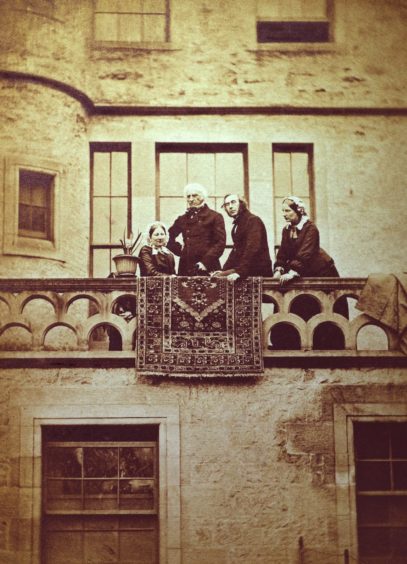

However, it was only when Ludovic recently rediscovered some old dusty photograph albums in a cabinet at his uncle’s home on the Balcarres Estate, near Colinsburgh, in Fife, that he found himself taking his first look into his ancestors’ unpublished and most personal of records.

Forgotten

The albums, filled with images from another age and almost completely forgotten for over 70 years, had rarely seen the light of day.

Yet here were the faces of the people who had been so instrumental in forming the Lindsays’ more recent history – part of a timeline that can be traced back centuries, to before the Norman conquest.

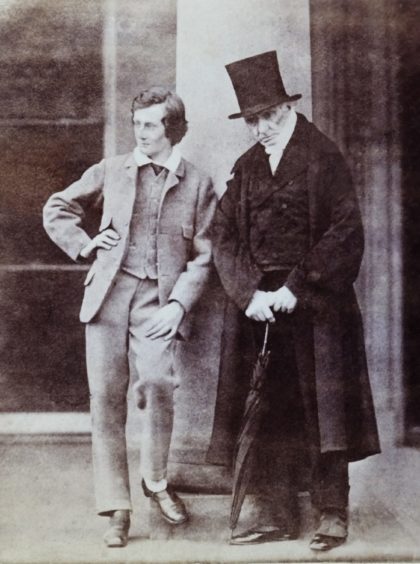

“The resurgence of the family coincided with the birth of photography in the 1840s, which encouraged the family to capture moments of their leisure pursuits and the part they played in the events of their time,” explains Ludovic, 64.

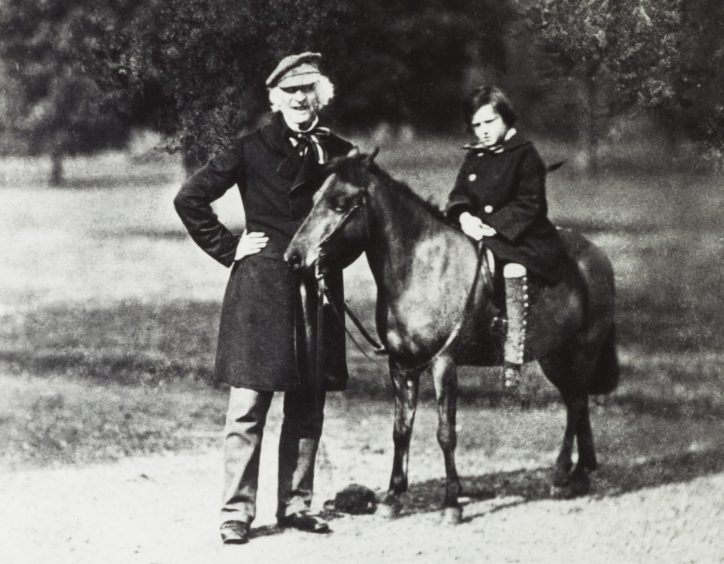

“As I investigated further, it became clear that within these volumes there was a wealth of annotated portraits that over time would allow me to finally identify these more recent ancestors – beginning with James, ‘Lord Bal’, 7th Earl of Balcarres, who appears in the earliest daguerreotypes of about 1840.

“The collection served as a social history, recording the rapidly changing industries they were involved in and the relationships with their staff on which their way of life depended.

“Some of the earliest daguerreotypes in the family archive also pointed to the enduring affinity that would develop between photography and the Balcarres country house.

“However, I also found remarkable pictures that revealed other aspects of their lives – from the people who worked for them to travels to what were then exotic lands pursuing scientific discoveries.”

Descendants

Ludovic needed a structure on which to hang the images, so he focused on just those descendants of the Lindsays who had lived, for part of their lives at least, at the main family homes of Balcarres, Haigh Hall (Wigan) and Dunecht (Aberdeenshire).

This meant that it would include all those who had descended from James, 5th Earl of Balcarres (1691–1768). A few cousins were also able to unearth similarly long-forgotten albums.

The result is a book – The Lindsays of Balcarres: A Century of an Ancient Scottish Family in Photographs – where the reader encounters a gallery of colourful characters.

They include Elizabeth Lindsay, who married the 3rd Earl of Hardwicke in 1782 and became Vicereine of Ireland; her great-nephew, Robert, who joined the Guards at the outbreak of the Crimean War and carried the Queen’s Colours to the heights of Alma, earning him the first of two citations for the Victoria Cross; and his brother-in- law, Alexander, the 25th Earl of Crawford and his polymath son Ludovic, who together rebuilt the family library, Bibliotheca Lindesiana, into one of the world’s finest.

The book also spotlights James Ludovic, known intimately as ‘Udo’ as a young man and latterly Ludovic, who saved the Royal Observatory of Edinburgh by giving the entirety of his scientific library, along with all its apparatus, to the observatory on condition that the government continued to fund its operation.

About the author

Brought up in London, today’s Ludovic Lindsay studied at Ampleforth College in Yorkshire – a Catholic boarding school on the edge of the Yorkshire Moors.

After a year working in South America, he worked at Christie’s auction house for four years – where his late father the Honourable Patrick Lindsay was senior director – before dealing on his own.

Realising that he was “not a very good salesman”, and much more interested in creative pursuits, he found himself working with a small team of documentary makers, which he loved.

Establishing his own production company, the now divorced father-of-two has spent the past 30 years making documentaries on everything from Africa to his passion for motor sport. He particularly enjoys research.

However, the now 64-year-old, who left London for the rural beauty of Marlborough in Wiltshire 20 years ago, never expected to write a book.

“I was always intrigued by family history on visits to Balcarres Estate as a child,” he says.

“I knew there was a lot of stuff there. I suppose in every generation of every family, there’s always going to be someone who’s going to be a little bit more interested than anyone else.

“My father’s first cousin wrote two or three books on the family.

“Until I left school, I spent all my summers at Balcarres, and it was a magical place.

“I always questioned – ‘where did this all come from?’ and so on – and for a while I assumed it had always been there, that type of thing.

“But actually, writing the book, I learned so much more about the family.”

Balcarres history

One of several East Neuk estates, and with family links to Angus, Balcarres has been in the possession of the Lindsay family since 1586 and has undergone much change over the years.

The Earl of Balcarres was created in 1651 for Alexander Lindsay, 2nd Lord Balcarres and since 1848 the title has been held jointly with the Earldom of Crawford. The holder is also the hereditary clan chief of Clan Lindsay.

The family has strong links with the immediate community, in particular, the village of Colinsburgh that takes its name from the 3rd Earl of Balcarres, Colin Lindsay.

In the early 18th century, he built the village directly south of the estate to resettle soldiers who’d served in his regiment.

Ludovic suggests that it’s perhaps no coincidence that the golden age of photography neatly coincided with the revival in fortunes of the Lindsays.

Generations of the family had been closely aligned to affairs of state, but siding with the doomed Stuarts during the civil war and the Jacobite cause brought on a period when they lost much of their status.

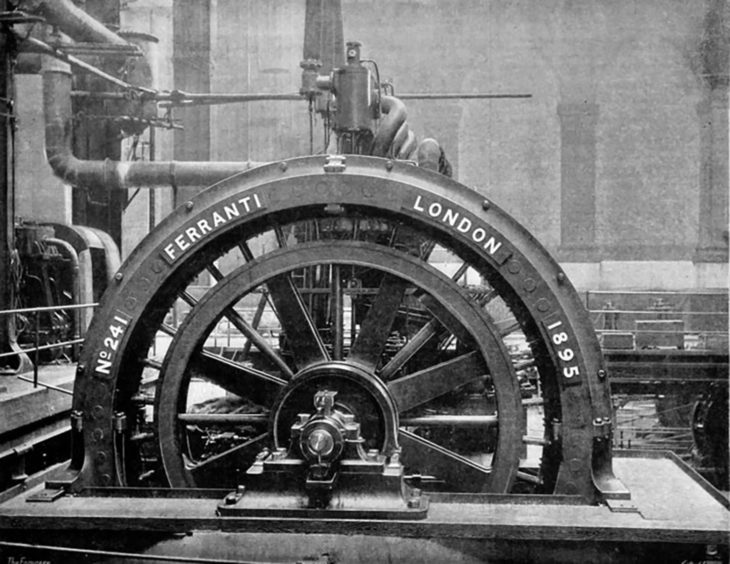

Fortunately for them, marrying into the Bradshaigh family in the late 18th century, whose lands lay over some of the country’s most productive mineral seams, near Wigan, meant that they now found themselves at the potentially extraordinarily profitable coalface of the industrial revolution.

This allowed them to embrace new opportunities and rebuild their estates while profiting from the new technologies.

Impact of photography

It was the pioneering Louis Daguerre who publicly announced the first viable photographic process in 1839.

In around 1840, James Lindsay, 7th Earl of Balcarres and something of a technologist himself, became curious and commissioned portraits of his family and staff at Haigh Hall.

As technology developed further, the British aristocracy were the first to indulge in this new technology.

Haigh Hall was the perfect environment for photography to blossom. There was always available space to create a studio, which the enthusiast could fill with equipment from outfitters such as Horne, Thornthwaite & Wood or George Houghton & Son.

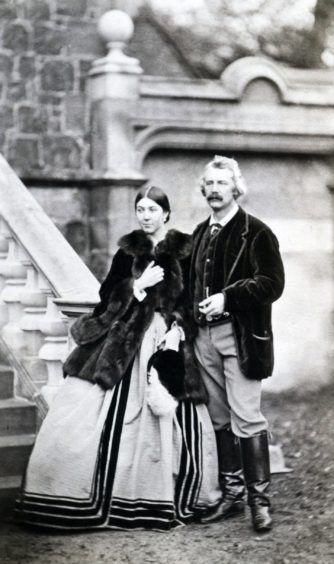

Coutts Lindsay would build his own studio at Balcarres, his Scottish home.

Ludovic, who also has an interest in photography, explains that while photographs of family and staff, buildings or interiors may seem unimaginative today, they chronicle the lives of 19th century antecedents better than any other medium.

Finding out about the men in the pictures was relatively easy, he says. For those who had been involved in affairs of state, there were decent records.

For the women, though, it was more challenging as they rarely wrote about themselves.

Fortunately, many of his ancestors kept diaries and letters where they wrote about their siblings or their daughters or nieces.

“This meant it was a matter of cross referencing – reading one person’s diaries about someone else’s,” he says.

“Nothing had been written about them at all, yet I discovered they went on fascinating expeditions to Egypt or America or they tried to play their part while supporting their husbands and the business side. They were really interesting.

“It was heartening actually – a can of worms. You didn’t know what you were going to find. They had a very strong religious ethic as a lot of people did in that period. It was heartening.

“But I still feel it would nice to do more on the individual women.”

Ludovic says he felt a connection to some of his ancestors in the photographs and started to recognise “face types” down the centuries.

“You feel a connection to individuals for a strange reason – some might say it’s something to do with reincarnation or something weird like that,” he says.

“When you work on photos – because a lot of them were in bad shape – you are looking at those individuals and get to know every bit of them.

“I write somewhere in the book, and I’ve often felt it, ‘people only truly die when their name is mentioned for the last time’.

“They sort of come alive again. They haven’t been forgotten. That was definitely how it felt doing this.”

Striking a balance

Ludovic tried to strike a balance between biographies and the social history of the Lindsay family.

However, he discovered a few surprises along the way as well.

“My great great uncle Robert Lindsay – he was an interesting one,” he says.

“One of his first jobs was escort the Tsar when up at Balmoral. He went to Australia, met a young woman who he later married.

“In the 1880s, Robert’s mother in law hosted a cricket match at their place in Melbourne when the English came across.

“After England won two of the three tests on the tour, she thought she’d better give them a prize – so she goes up to her bedroom and gets this little Egyptian thing and presents it to the captain Bligh. That became the Ashes!

“Another story involves my great great grandfather on the front cover of the book. He had a niece, Margaret Majendie, who married this rather senior much older Field Marshall, Lord Francis Grenfell. “It turns out that he was a well known soldier at the time and they named Grenfell Road after him, which of course is where the Grenfell Tower is. It’s rather poignant.

“Then there was the great ship – he had this fantastic yacht Valhalla which he’d fill up with scientists, writing about nature and astronomy.

“Then there was another great uncle who travelled North America working on mines.”

Ludovic says the family also collected Christian art and started collecting books on an “industrial scale”.

“They wanted a library that encapsulated the knowledge of the world,” he says.

“I was relieved to discover they weren’t just doing the aristocratic thing of hunting, shooting and fishing but had a spirit of adventure and thirst for knowledge as well.”

*The Lindsays of Balcarres: A Century of an Ancient Scottish Family in Photographs by Ludovic Lindsay is published by Pimpernel Press, £60. Available from October 7.