Can saltmarsh restoration help slow down the impact of climate change-related sea level rise that’s threatening many iconic links golf courses? Michael Alexander finds out more from St Andrews University conservationist, Dr Clare Maynard.

Venture out to the end of the West Sands at St Andrews during a spring tide, and the forces of coastal erosion can be self-evident.

During the highest of tides, the base of sand dunes can literally crack and crumble before your eyes, as neighbouring stretches of rock armour defences stand up to the waves.

According to a recent climate change study by Climate Central – an organisation comprising scientists who research climate change and its impact – parts of the ‘Home of Golf’ could be underwater within 30 years.

Its interactive maps showed the hallowed links of the Old Course at risk of flooding if current trends continue.

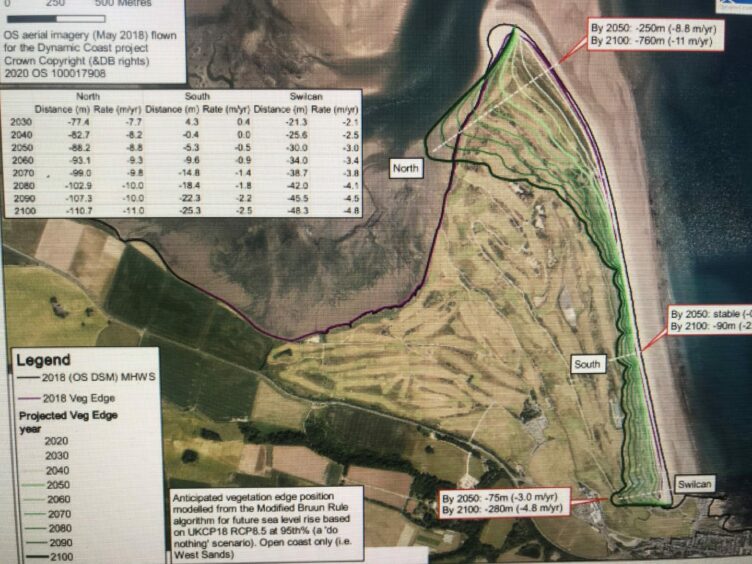

In a separate study, the Scottish Government’s Dynamic Coast report, which sets out resilience and adaptation options for St Andrews Links, has warned that erosion and flood risk are “real and growing threats” to the St Andrews Links.

Projections expect St Andrews to experience sea level rise of up to 0.9 m by 2100, in turn quickening erosion.

Dynamic Coast research starkly predicts that under a worst case “do nothing” coastal management strategy, the Out Head section of West Sands at St Andrews will “retreat into the links by up to 240 m in the next 30 years and up to 750 m by 2100”.

With evidence from the maps, the government is encouraging local authorities to prepare coastal adaptation plans.

In 2018, golf’s governing body the R&A launched Golf Course 2030, an initiative to address the challenges posed by a global warming.

A particular focus was on coastal change, with some of Scotland’s iconic links courses vulnerable to erosion and flooding from even minimal rises in sea levels.

It came as the Climate Coalition, which represents more than 130 organisations in Britain studying the effects of climate change, used the historic Montrose Links in its 2018 report “Game Changer” as an example of the threat.

When sand dune rebuilding work at St Andrews was highlighted during recent COP26 coverage on BBC’s The One Show, a spokesperson for St Andrews Links Trust said: “”If you look at the landscape that we are in, it’s quite low-lying, it’s quite near the sea, and it is going to be vulnerable.

“Golf has been played here for 600 years. It should still be played here in hundreds of years from now.”

But with the entire UK coastline said to be in danger of flooding as a result of rising sea levels, and warnings that a total of £1.2 billion worth of infrastructure in Scotland could be threatened by 2050, could the expansion of “nature-based” approaches to the threat of erosion enhanced flooding have an important role to play?

Can saltmarshes play a role?

Dr Clare Maynard of St Andrews University is head of the Green Shores Partnership – a collaboration between coastal landowners and community organisations that has created fringe saltmarsh habitat in key sections of degraded shoreline.

Multi-million pound seawalls and ‘managed realignment’ – where bits of land are given up to the sea to alleviate flooding elsewhere – are two existing approaches to managing sea level rise elsewhere.

However, a third way is planting of saltmarshes which were proven to reduce the impact of erosion and flooding of the land behind it.

Dr Maynard says climate change and rising sea levels is “undoubtedly” a threat to golf course shorelines.

Climate change is increasing storm weather and sea level rise, both of which lead to flooding and erosion, and thus the potential loss of golf course land.

What Green Shores is doing around the Eden Estuary and elsewhere, however, is exploring fringe saltmarsh restoration and how they can help protect coastlines from flooding and erosion, providing a stable shoreline that acts as a wave break.

“Saltmarshes have been impacted by human activities and are increasingly vulnerable to climate change,” she says.

“Time is on our side however, to reverse the damage before it’s too late.

“So, around St Andrews, or more specifically, the Eden Estuary, we’ve been using saltmarsh transplants, harvested either from natural marsh, or grown in a polytunnel, to simply plug any gaps in the marsh front or to recreate marshes in vulnerable shoreline sections.

“In some locations, we’ve found that we need biorolls – biodegradable wave breaks that reduce what we call the wash out rate, or how many transplants are washed away by the tide before the roots take hold to keep them in place.”

Multiple functions

Asked about the benefits of a healthy coastal ecosystem, Dr Maynard explains that all coastal habitats perform multiple functions, from wave protection, carbon sequestration and biodiversity to recreation or simply looking nice.

More specifically, golf courses benefit from healthy coastal ecosystems because they protect coastal courses from flooding and erosion.

St Andrews has a wonderful range of ecosystems, including cliff top habitats and rocky shores, to long stretches of sand dune systems, and not to mention the saltmarshes of the Eden Estuary and beyond.

Links golf courses also have an important role to play, she says, in long-term sustainable management of natural coastal ecosystems.

“All coastal habitats provide a buffer zone between us and the sea,” she says.

“Without these buffers, the impact of sea level rise like flooding and erosion will be that much worse.

“St Andrews Links play a leading role in Scotland by helping to protect and restore these habitats around the coast.

“In some cases that means simply reducing the impact of trampling, and in other cases more direct techniques such as transplantation.”

Widespread challenge

Of course, it’s not just St Andrews golf courses facing up to the challenge of climate change.

Dr Maynard has also been involved in a project at Royal Dornoch in the Dornoch Firth where similar challenges are being faced.

The 10th fairway on their Struie course, is increasingly threatened by coastal flooding, especially during high tides and storms in winter.

“We’ve recently just attempted a new approach for this site, with greenkeepers installing a storm fence across the upper shore,” says Dr Maynard.

“School pupils from Dornoch Academy helped us to plant saltmarsh behind the fence and we will monitor the success of the new technique over the coming months.”

Montrose erosion

The links at Montrose Golf Club also suffered severely from coastal erosion recently.

But to what degree has climate change increased the speed and severity of these sorts of impacts on these coastal ecosystems?

“In ideal natural situations, saltmarshes and sand dunes can be left to come and go at will,” adds Dr Maynard.

“It’s part of the natural process of habitat succession and replacement.

“But when we’re dealing with narrow fragments in front of valuable land, such as coastal golf courses, the need to act now to reduce the impact of climate change is urgent exactly because the impacts are increasing.

“Sand dune systems are front-line natural flood defences for coastal communities. But just as importantly, they are also a carbon store, helping to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in our fight against climate change.”

Threat to links courses

Of course, the R&A use venues all around the UK to host The Open Championship, which returns to St Andrews for the 150th next July. Links courses are all found in coastal landscapes.

In general, they all face common problems with sea level rise and climate change, says Dr Maynard. But location is key to how much they are affected. For example, the Dornoch Firth saltmarsh restoration site is more exposed to the elements, so they’ve adjusted their techniques.

What needs to be developed as a matter of priority, she says is a “toolbox of different methods” that can be explored across the various settings to help solve the issues.

“We passed the ‘do nothing’ scenario a few years ago,” she says.

“The situation is serious enough to warrant action now, while there is still time to restore natural coastal defences. If we do nothing, we will lose our coastal habitats, which will lead to greater flooding and erosion issues for our coastal landowners and communities.”

Eden Estuary trials

With St Andrews University having recently been ranked number one in the UK in The Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide 2022, it’s a poignant time for the institution to be at the cutting edge of finding climate solutions.

The Eden Campus at Guardbridge is designed for state-of-the-art research and business enterprise, as well as the university’s innovative low-carbon energy hub.

Dr Maynard’s position as biodiversity advisor at the campus is to help restore its biodiversity, taking it from a former brownfield site to providing the community, where possible, with pleasant spaces to walk, wildflower meadows and woodlands, as well as restoring saltmarsh along its shoreline.

She is also biodiversity advisor to the newly formed St Andrews Forest – another major effort by the university to address climate change and biodiversity issues.

Dr Maynard says Green Shores started with small trials in the Eden Estuary many years ago with the backing of the Links Trust, who with the Fife Coast and Countryside Trust, also champion the West Sands dune restoration.

She is full of praise for the “amazing job” carried out over the years by the conservation authorities –NatureScot and Fife Coast and Countryside Trust – as they deal with potentially conflicting interests of major employers and landowners around the estuary including St Andrews Links Trust arable farmers, and the Ministry of Defence.

Speaking about the St Andrews University Eden Campus on the former Guardbridge papermill site, she adds: “We’re the only place in Scotland to have two coastal restoration projects working side by side which sets a fantastic example of what can be achieved when we all work together to solve problems that affect us all,” she says.

“Given that St Andrews is my alma mater and home to the most famous golf course in the world, it’s hard not to be proud to be playing my part, and hopefully helping them to hold back the tide for generations to come.”