Michael Alexander speaks to investigative journalist and former RAF Public Relations Officer for Scotland Michael Mulford who reflects on the remarkable story of a Yorkshire-born lass now living in Fife who witnessed the horrific aftermath of war.

“As the four powerful Merlin engines of the Lancaster bomber held their steady note over the skies of Germany in 1945, Corporal Fourness, M, Service Number 474762, lay flat on the floor in the bomb aimers cramped area at the front.

“As the target loomed in sight 23-year-old Fourness kept as steady as possible.

“Then, at the critical moment, the young corporal on a unique first flight pressed the operating mechanism to achieve the mission.

“The equipment Cpl Fourness was using was not some ingenious WW2 invention.

“It was a Box Brownie camera first produced by Eastman Kodak in 1900 and retailed at one dollar.

“What was so different about this flight over war-torn Germany was not just that someone below the rank of sergeant was travelling in a Lancaster bomber but the fact she was one of two women on board.

“Now, in her 100th year, Mrs Margaret Overend, at her home in Fife, is almost certainly the last surviving woman to have made such a flight….”

Inspirational story

Investigative journalist and former RAF PR man for Scotland, Michael Mulford, is no stranger to aviation and the role played by the RAF past and present.

However, when Mr Mulford met 99-year-old Margaret recently and learned the extraordinary story of the Lancaster flight that took place shortly after VE Day more than 76 years ago, he was inspired to share an account of his meeting with Courier readers.

Mr Mulford, whose wife Sandy is one of Margaret’s carers, explained that several weeks after the war in Europe ended on May 8, 1945, and with the war in the Far East still raging, Margaret and her best friend LACW Kathleen Turner accepted an invitation from Canadian aircrew to go on the flight.

The aim of the mission was to get, for intelligence purposes, official photographs of bomb damage, and to drop leaflets for humanitarian reasons.

Earlier in the war, leaflets were used for propaganda purposes, urging Germans to abandon their homes – and their leaders.

In Margaret’s flight, the leaflets gave details of German Prisoners of War.

During the Second World War in Europe six billion leaflets were dropped.

Margaret explained that she’d had a career with the Midland Bank. But when she joined the WAAF (Womens Auxiliary Air Force) they had her doing vital war work – washing dishes.

“Then, one day, a senior officer asked me what I did in civilian life,” she said.

“When I told him I worked in banking I was suddenly lifted out of the kitchen and into the pay section!

“Absolutely everything we did was covered by the Official Secrets Act, which we all had to sign and stick to. I did tell my parents about the flight and my father managed somehow to get me a roll of film for my camera.”

Bird’s eye view

Margaret recalled how when the Lancaster climbed into the skies over Topcliffe in Yorkshire, she and Kathleen had the ultimate bird’s eye view.

“For the entire six-hour flight which stretched over 1000 miles, the two of us had to lie on our stomachs in the small area usually only occupied by the bomb aimer at the front,” she said.

“That day there were three of us crammed in the space. When the pilot banked the aircraft over the North Sea to change course, one moment we were looking at the sea, and the next it was the sky!”

Margaret explained how, as the aircraft flew over wrecked city after wrecked city, the official intelligence photographers did their work.

Margaret’s Box Brownie captured a few images, limited though they were by the rudimentary nature of the camera.

She keeps them as a profound memory of the trip. “Everyone should make memories because the day will come when you need to remember,” she said.

“As we looked down at the damage done by constant bombing I thought what I was seeing was simply appalling.

“On the other hand you have to remember what the Luftwaffe did to our cities like London, Coventry, Liverpool and many others.”

Mixed emotions at bombing

Reflecting on Margaret’s experiences, Mr Mulford told The Courier he finds her story remarkable.

“The idea that two women could lie face down in the cramped bomb aimers bubble for a flight which lasted six hours and covered 1000 miles over war- ravaged German cities with World War Two still raging in the Far East was extraordinary!,” he says.

“The fact they did is a testament to the spirit of the young people of the nation that they volunteered to play their various parts defending home and family.”

However, the 75-year-old also has mixed emotions when he reflects on the bomb damage that was sustained on German cities – and British cities – alike.

During the Clydebank blitz of March 1941, for example, when the Luftwaffe carried out a pair of air raids on the shipbuilding and munition-making town, the official death toll was 528. That included 14 members of the extended Rocks family at 78 Jellicoe Street.

Patrick Rocks Snr came home from work to find utter devastation and his entire family gone, including his own wife and children, and his son, daughter-in-law and their family.

The victims included five children aged six and under.

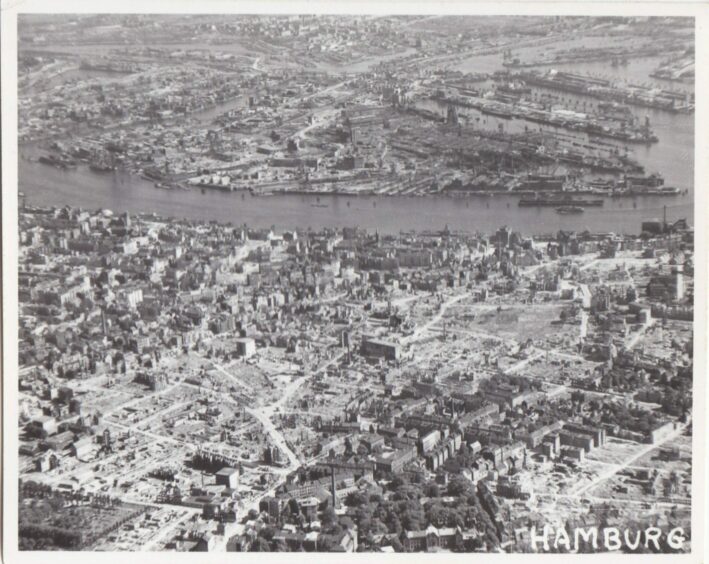

“The same hideous nightmare was undoubtedly played out in German cities like Hamburg, Cologne and Dresden,” says Mr Mulford, “as Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris, head of RAF Bomber Command deployed his aircraft, often a thousand at a time, to pulverise areas of cities rather than specific targets.”

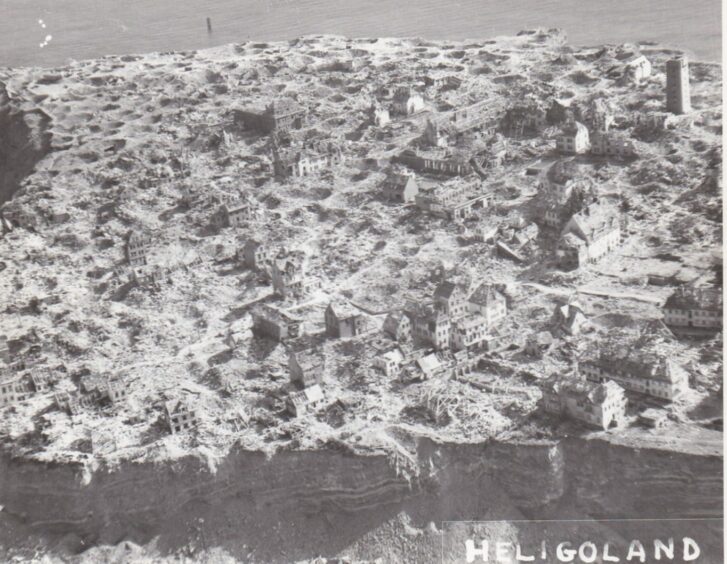

That is what Margaret gazed down on in the unique opportunity afforded by the flight, as the photo evidence – never seen before today – shows.

Utter devastation

The images show utter devastation with many buildings barely even showing what’s left of their foundations, let alone the human cost of what had happened.

Mr Mulford notes, however, that military experts and historians – far less the general public whose loved ones died in German or British bombing raids – have never agreed, and will never agree, whether or not Bomber Harris was correct to adopt the strategy he did: of pulverising whole areas of cities with the inevitable, ghastly consequences for the civilian populations.

Mr Mulford, of Cupar, has attended the annual memorial service in Clydebank for the hundreds wiped out in German raids there.

He says a “more solemn, sombre event is difficult to imagine”.

Having been “proud and honoured” to work for the Royal Air Force as a civil servant for 11 years as PRO Scotland and principal spokesperson on military Search and Rescue operations, the Dundee-raised former Courier and STV journalist, who toyed with the idea of joining the RAF in 1972, is in no doubt that the RAF is a “force for good”.

They set themselves the highest of standards in all their work, he says, and when the political masters order them to use their bombs and missiles, they do so with the greatest care to avoid collateral damage as much as is humanly possible.

Technology not available to the Second World War aircrews is a huge advantage today.

The difference between targets then and now is using that technology to minimise civilian losses.

On “mature reflection”, however, Mr Mulford does not think now that carpet bombing really shortened the Second World War.

“I look to the brilliant work at Bletchley Park where the Enigma Code was cracked as definite evidence of why we had two years less of hostilities,” he says.

“The supporters of the effect of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki do not see it that way.

“The next city in line for being wiped out was undoubtedly Berlin.”

Shocking photographs

Mr Mulford says the official intelligence photographs from Margaret’s epic flight shocked him, particularly those of Hamburg.

As part of a sustained campaign of strategic bombing during the Second World War, the attack during the last week of July 1943, code named Operation Gomorrah, created one of the largest firestorms raised by the RAF and USAF in the Second World War, killing an estimated 37,000 civilians and wounding 180,000 more in Hamburg, and virtually destroying most of the city.

Before the development of the firestorm in Hamburg, there had been no rain for some time and everything was very dry.

The unusually warm weather and good conditions meant that the bombing was highly concentrated around the intended targets and also created a vortex and whirling updraft of super-heated air which created a 460 meter high tornado of fire.

Mr Mulford finds it amazing that Margaret managed to capture a few images of the devastation herself with her Box Brownie.

He agrees with her that keeping those as a record for future generations is so important, as is her story.

For the Canadian aircrew on Margaret’s flight, however, it was almost a perverse opportunity to see in daylight for the first time targets they had bombed many times at night.

The navigator remarked they had been to the Ruhr so often the Lancaster knew its own way!

For Margaret, the trip was anything but business class travel. They were not in danger of being shot down but the Lancaster had had lots of war wounds and repairs done to keep it flying – just.

Final thoughts

“My final thoughts on Harris and his strategy centre on the infamous raids on Dresden,” says Mr Mulford.

“Official estimates put the death toll at 25,000, many of whom were incinerated in the crypts of churches in the firestorm.

“The German propaganda machine put the death toll at 200,000.

“They won that battle. The fact it took decades before a bomber crew memorial in Britain was built tells me that Harris’ legacy was not a glorious chapter in too many history books.

“RAF aircrew losses amongst bombers was some 55,000 and of those more than 20,000 have no known grave.”

After the war Margaret never lost contact with her friend Kathleen, and they met many times. She passed away some years ago.

Yorkshire lass

Leeds-born Margaret married Ken in later life and their travels took them far and wide. They settled in Fife and had many happy years before Ken passed away.

“You learn very quickly meeting Margaret that the warm Yorkshire spirit and the enduring love of her homeland is as strong now as it has been for nearly a century,” smiles Mr Mulford.

“Everyone is greeted with ‘darling’ and she keeps in touch through friends and local publications in the White Rose County.”

As her centenary edges ever closer Margaret, like so many of her generation, is assuming nothing.

“How might I celebrate my 100th birthday – if I get there?” she asks.

A flight in a military aeroplane courtesy of the RAF perhaps?

“No,” she says firmly, “it will not be in any aeroplane!”

Who knows, maybe an RAF fly-past to salute a remarkable lady and commemorate a unique flight?