Years before Britain’s Bletchley Park was decoding secret messages during the Second World War, St Andrews historical artist Jurek Putter’s late father helped Poland counter the threat of Nazi Germany’s Enigma machines. Michael Alexander met Jurek who has now immortalised his father’s remarkable story in three special prints.

When artist Jurek Putter decided to dedicate his professional life to a series of drawings depicting the history of his hometown St Andrews during the Middle Ages, he was driven by a desire to restore a nation’s lost heritage.

For centuries, St Andrews was the principal city of a once independent nation exercising its power by being at the centre of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland.

Pilgrims converged on the small Fife settlement – a place made holy by claiming to possess the remains of Saint Andrew the Apostle.

Many others came to take up scholarly pursuits at Scotland’s oldest university at a time when the east coast was closely linked to the trading ports of Europe.

Yet most of the drawings, illustrations and paintings that provided a visual record of Scotland and her people – prior to the 16th century – were largely stolen, destroyed or sent abroad amid the upheaval of Scotland’s Protestant Reformation.

Fascination with history

Jurek’s fascination with history was at least in part inspired by growing up in post-war St Andrews.

Born in Edinburgh in 1944, however, his life was also shaped by overseas forces.

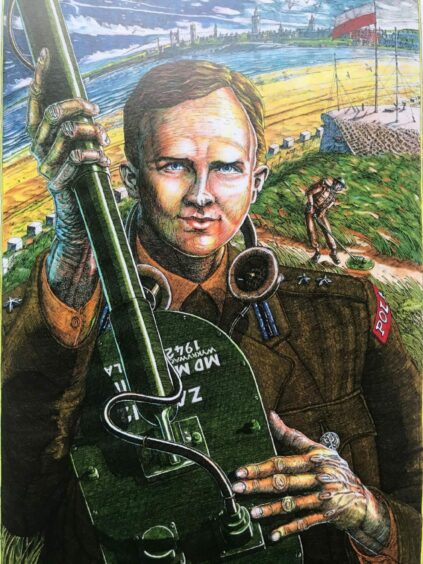

When Panzer divisions of the Germany Army blitzkrieged Poland on September 1, 1939, igniting the Second World War, Jurek’s father – a diplomatic courier also called Jurek (originally Jerzy Augustyn) – was amongst thousands of Polish troops who fled to France then to sanctuary in the south of England.

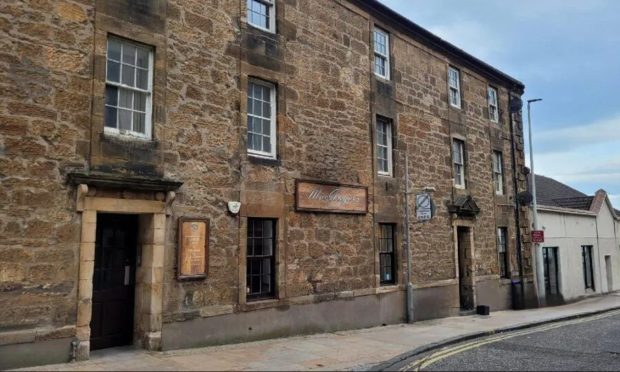

Regrouped and re-quipped on the east coast of Scotland to initially build a long chain of coastal defences against imminent invasion, Jurek’s father was based at the Ardgowan Hotel in St Andrews.

The Polish soldier, who also worked for a spell as a senior administrator at Taymouth Castle military hospital, at Kenmore, married Fife girl Georgina Rader, with Jurek their resulting son.

After the war, along with 90,000 of his fellow countrymen, Jerzy decided to settle in Scotland.

‘Free and independent Poland’

Like many of his compatriots who fought for a free and independent Poland, he risked arrest if he returned to his Soviet-occupied homeland and changed his name to Putter. The family settled in St Andrews in 1946.

Growing up amid the eclectic nature of the university town, there’s no doubt Jurek was influenced by his father who viewed Scottish history, culture and its people from the perspective of an outsider.

Fascinated by politics, divisions and frontiers – including the Roman occupation of Caledonia – Jurek’s father told him: “Forget all this Highland bagpipes tartan nonsense – the ugly reality of Scottish history is very different!”

The trigger for Jurek’s historical works, however, came in 1964 while studying at Edinburgh College of Art.

He was approached by a respected Scottish educational history writer Miss Scott-Moncrieff, who said to him: “The Scots don’t know their real history. For them, history starts in 1560, and they can’t see themselves as a people or culture”.

This inspired Jurek to create a series of prints on the largely forgotten chapter of Scandinavian Scotland. However, it also inspired him to go further.

Historical Illustration project

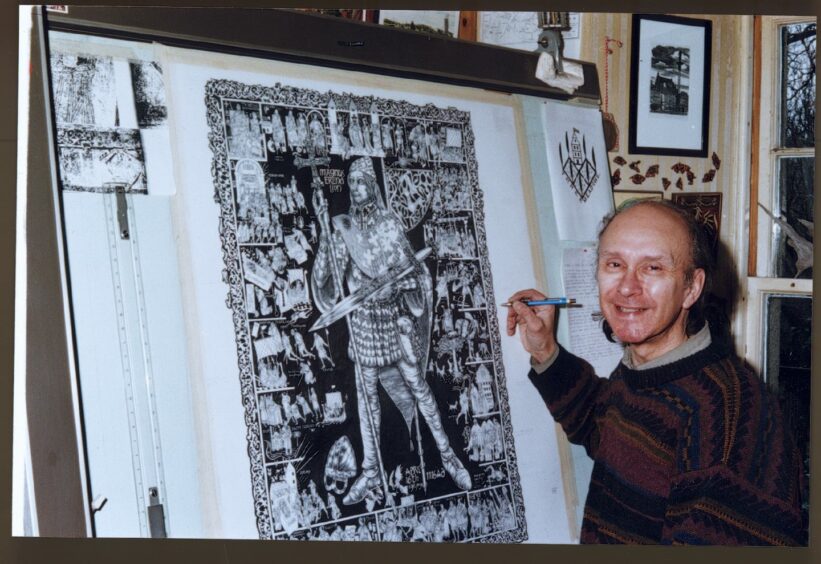

Turning his back on a lucrative career as a commercial artist when he graduated in the mid-1960s, Jurek returned to St Andrews with an idea: to embark upon a decades-long project that would produce a series of major research prints.

The idea was each one would be a reconstruction of life in pre-Reformation Scotland from 1460-1560 – the “last true century of indigenous Scottish culture” with most of them centred on his home town.

It was his father who suggested he throw open the doors of his studio so that the Scottish public could see the evolution of his works “from inception to completion”.

By proving that this largely overridden version of Scottish history was not seen as fantasy, it would generate confidence in the buying public.

It was an approach that worked. Jurek became a lauded authority on his father’s adopted land.

Over the decades, he produced dozens of major research prints, each one a reconstruction of life in medieval Scotland – most of them centred on St Andrews – the “treasure house of a once powerful nation”.

Jurek’s Grafic Orzel Design Studio in South Street has long since closed and his Historical Illustration Project of St Andrews long since completed.

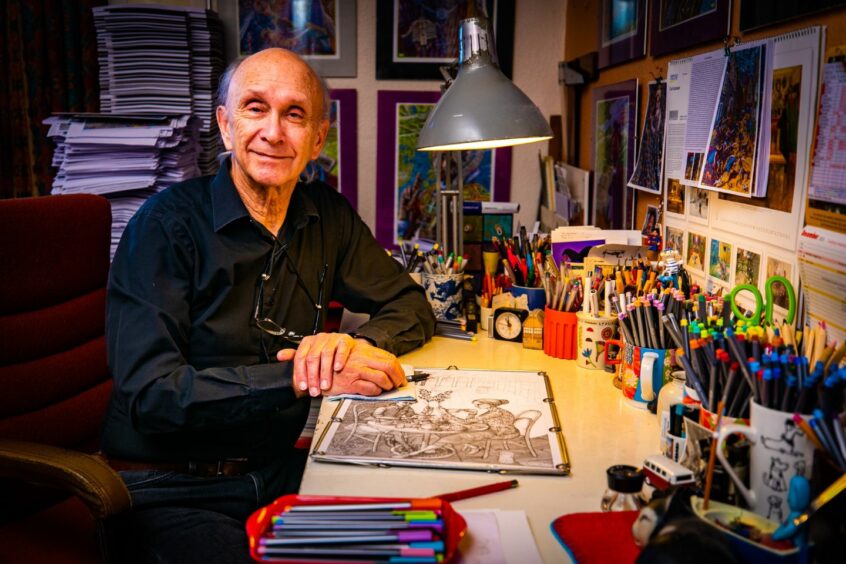

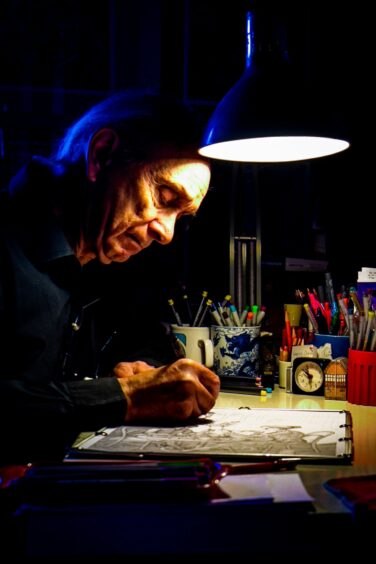

Despite keeping a relatively low profile in recent years, however, the now 77-year-old continues to work privately and has recently produced a series of prints that pay tribute to the life and influence of his late father.

In essence, they focus on a “completely unknown story” of the role played by his father before the war as Poland sought to counter the threat posed by the German Enigma machines, long before the decoding work of Britain’s Bletchley Park during the Second World War.

The prints also chart the influence those experiences had on Jurek’s father as he settled and worked in Fife after the war.

Father’s remarkable pre-war role

Settling back into his chair as The Courier caught up with him at his home in St Andrews, Jurek explained how he’d “waited a long time” to do these three prints.

“My father was a pre-war diplomatic courier and a graduate in economics,” he says.

“His first major job was with the Polish Foreign Office, and it coincided with the Polish concern for the rise of what was to become Nazi Germany.”

Born in Lwow, Poland, in what was then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Jurek explained that after graduating in economics and maths from the renowned Lwow Polytechnic, the first job his father got was as a diplomatic courier serving Polish embassies, consulates and trade missions in the Balkans.

The rise of an increasingly militaristic Nazi Germany led the Polish government to invest heavily in intelligence gathering with an emphasis on deciphering diplomatic and military radio traffic.

The Germans had seen the potential for upgrading a commercial cyber coding machine entitled Enigma, which the Germans deemed unbreakable.

However, the Polish Army Cypher Bureau successfully deconstructed the working of the Enigma machine, built replicas and broke the codes using a unique machine called the ‘Bombe’, years in advance of the British efforts.

Jerzy, whose code name was ‘The Book maker’, was the “eyes and ears” of his country abroad at the time with an emphasis on assessing radio antennae installed in German enterprises.

In the late 1930s he worked North Africa from Alexandria to Casablanca and Marrakech, where the Polish Cyber Bureau had a listening post.

“The post followed the German Navy as it expanded and extended its reach into the South Atlantic,” explains Jurek.

“The German Navy’s use of Enigma was the best managed, with almost flawless transmission procedures and upgraded with the latest machines and techniques.”

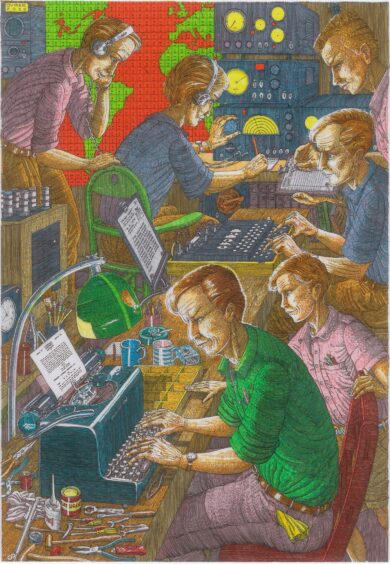

Jurek explained that when he was a boy, his father told him how in the Polish Commercial Consulate in Marrakech, there was a very secure room without windows where the German Navy’s radio traffic was being actively tracked almost daily.

It was dramatically bathed in red light to heighten and focus concentration, with only the all important tuning dials and directional aerial scanner dials illuminated in pale green.

It was a dangerous time with two Polish Foreign Office personnel killed in Marrakech ostensibly by agents working for the German Intelligence service – the Abwehr – who suspected the Poles were on their tail.

Prints

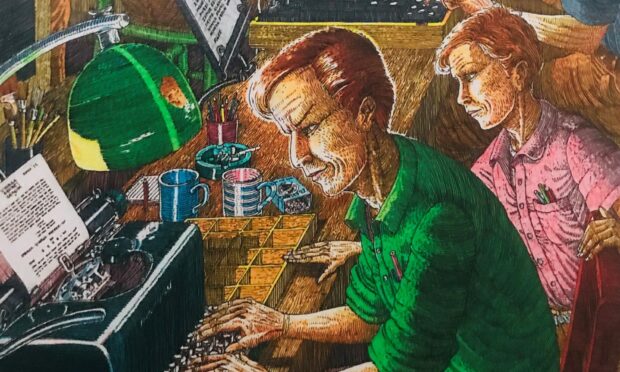

It’s through his print The Broken Remington that Jurek introduces the reader to this topic.

Jurek recalls how as a nine-year-old in 1953 St Andrews, in his father’s old cottage workshop to the rear of Jannetta’s ice cream shop on South Street, his father, while trying to repair an old Remington typewriter, started to talk about the room in Marrakech. Later in life he would tell Jurek more.

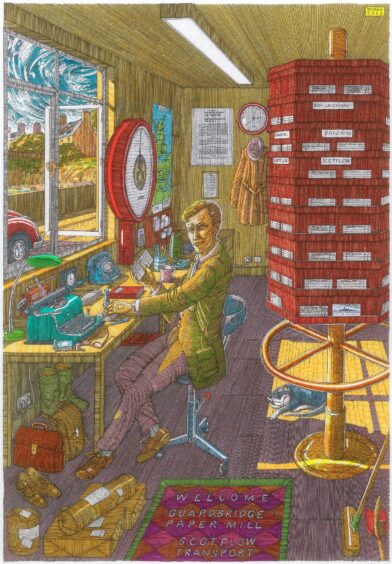

In a second print, however, called The Weighman, Jurek depicts how his father used his pre-war influences to re-organise the office at Guardbridge paper mill where, post-war, he secured a job as the weighman having initially started work as a labourer in the mill’s shaker shed in 1947.

“The first thing he did was set about organising the weighman’s office to prevent the general public coming in because there had been a corruption issue,” he says.

“There had been fiddles going on, so he wanted to keep the public out.

He insisted on having a telephone and designed new forms for when trucks came in, so that weighing tickets were put in a revolving octagonal drum.

“Drivers would say ‘aye you’ve done a great job with the office but now we can’t come in for a tea and a coffee’ and he would mutter ‘yes, and the corruption’ – always said very quietly under his breathe.”

The picture includes the front end of Jerzy Snr’s Beetle car – bought by his son. Subtly, the drum also included a picture of a German warship.

“It was his way of remembering the past,” smiles Jurek, adding that his father always wore a corduroy coat and was a man of few words with a very dry sense of humour.

“What he was essentially doing was he was restoring something of the imagery and iconography of his past from 1930-1938/9. It was a kind of inner joke. He introduced the tools of his past profession.”

‘Almost died’

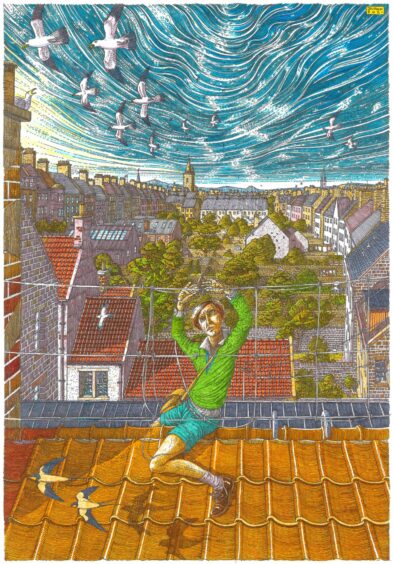

The third picture in Jurek’s series is called Aerials of Marrakech remembered.

It depicts nine-year-old Jurek on the roof of one of the old buildings behind the old Co-op in South Street, St Andrews, in 1953, stringing up an aerial.

The great radio adventure was born out of a rainy day’s rummage in the roomful of junk behind Jannetta’s, still known then as Mrs Ireland’s cottage, after the lady who had lived there. When she died it was crammed floor to ceiling with redundant equipment.

One Saturday morning, Jurek set about exploring and, underneath a towering pile of drawers full of crockery, he uncovered a green metal box containing what turned out to be a broken wartime-era radio receiver. It was stamped WD indicating War Department.

After showing it to his parents, Jurek took it to Stuart Mark, the local radio and TV repairer.

A “fantastically impudent” man who always wore brogue shoes, checked shirt, bow tie, half-framed glasses and had red hair beginning to turn orange, Jurek recalls Mr Mark rotating the fine tuning dial and confirming there were two dud valves.

But then he said: “Aye, but where’s the other half? Where’s the transmitter?”

Once fixed, and paid for by Jurek himself out of money he earned with part-time jobs, he took the radio back to his workshop where his father mused “you need an aerial” similar to what was used in Marrakech.

He smiled and told Jurek about the pre-war Marrakech “trade consulate” and the antennae array under the parapet, tuning in to the transmissions of German ships and u-boats.

Jurek laughs when he recalls using hundreds of metres of wire to construct the aerial on the roof high above South Castle Street.

However, he “almost died” the first time he went up after slipping on the pantiles and only the guttering stopping him from falling to the street below.

After borrowing a ladder from Mr Fulton of Black & Fulton slaters around the corner, he erected the aerial, divided into bands.

Contact with Polish fishing boat

With the further help of his father who talked about the need for a switching box, Jurek has never forgotten the irony of what happened next.

As they sat down to test the crude array they’d set up, the first signals received were from a Polish fishing boat, advising his position to his Mother Factory Ship anchored 12 miles off St Andrews. “Kaszuby, Kaszuby, Kaszuby. Korchon na Matka Kura!” Kaszuby was the name of the factory ship, the rest was ‘Chicken to mother hen!’

As the title suggests, it’s a true case of ‘Aerials of Marrakech remembered!’