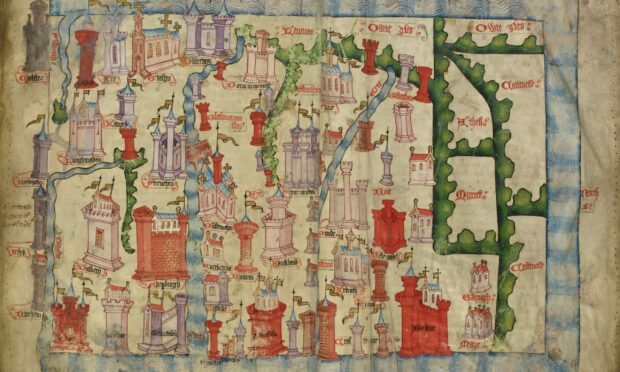

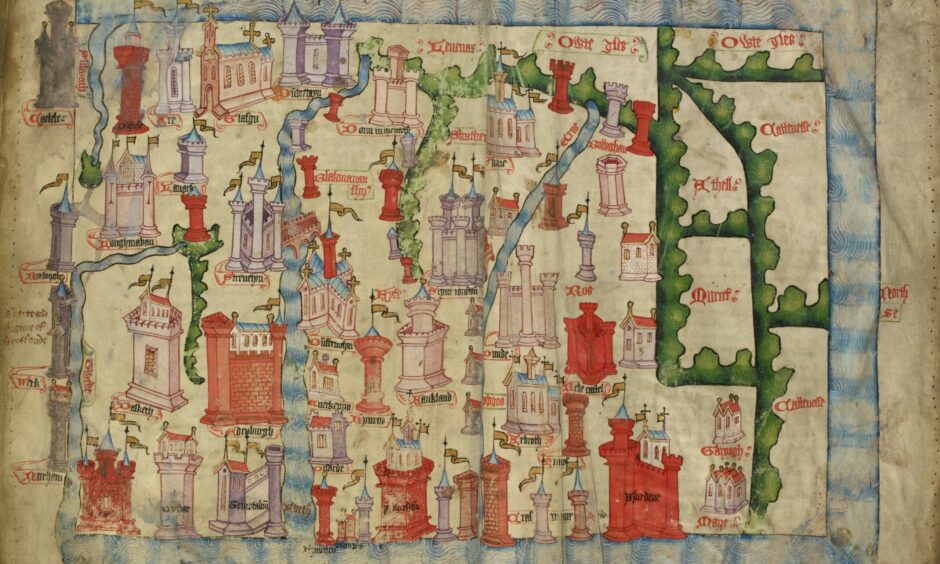

It’s a striking depiction of Scotland in the 15th century – a colourful map boldly locating castles and walls of medieval towns.

In many places, including St Andrews and Arbroath, there is a greater emphasis on churches.

However, this first detailed map depicting the Kingdom of the Scots was not created to aid navigation.

Instead, it was drawn up by an English ‘spy’ in the 1400s to highlight the riches of Scotland and justify a potential English invasion.

It’s thought the map was drawn from knowledge gained by English chronicler John Hardyng on a secret mission to Scotland, on which he was sent to spy out the land by the English King Henry V.

Hardyng included the map in his later Chronicle, telling the history of England and its neighbours.

St Andrews exhibition

Now, visitors to the Wardlaw Museum at the University of St Andrews can see the original Hardyng Map of Scotland for themselves.

It’s on loan from the British Library as part of its Treasures on Tour programme, until Sunday July 3.

Matt Sheard, Head of Experience and Engagement at Museums of the University of St Andrews, said visitors can explore the Middle Ages in depth as the map is being displayed alongside another exhibition, Cult, Church, City.

This brings together items from across the UK to tell the story of St Andrews during this period.

“It’s the most detailed map of Scotland at that time,” Matt tells The Courier.

“There have been depictions of Scotland in maps before this. But a map that shows this many towns and in this much detail doesn’t exist until Hardyng creates this one.

“It’s intended to give an impression of the kind of richness and luxury of Scotland.

“There’s big fancy churches, there are walled towns, there are castles, and it’s intended to encourage the king to invade Scotland and to claim sovereignty over it.”

Spying mission to Scotland

Matt explains that Henry V had sent Hardyng to Scotland in 1418 to “spy out” the country, to see whether it was worth invading and to plan how an invasion might take place.

There’s some debate over how much time Hardyng actually spent in Scotland over three years.

However, when he returned to England, King Henry V was on his deathbed and an invasion didn’t take place.

“It seems that Hardyng spent the next 30 or so years feeling a bit bitter about it,” says Matt.

“He really wanted England to claim sovereignty over Scotland, and it didn’t happen.

“So he wrote this Chronicle in 1457. It’ a big book. It’s a verse history. It’s poetic about the history of England and its neighbours including Scotland. It includes this map as part of the book which he presents to Henry VI.

“The plan is to try and encourage Henry VI to invade Scotland which he doesn’t do either. But that’s what Hardyng was trying to achieve.”

English aggression

Scotland, as an independent sovereign nation, was no stranger to the aggressions of invading English armies over previous centuries.

However, by the 1400s, after again gaining independence, Scotland was richer and flourishing. Take St Andrews. In the 1200s, the cathedral wasn’t complete.

Yet by the 1400s, it was the biggest cathedral in Scotland, attracting pilgrims from across Europe.

The power and influence of the Catholic church is evident on the map at that time with key churches including St Rule’s in St Andrews and Glasgow Cathedral very prominent.

“For St Andrews that’s particularly significant as it’s the centre of church power in Scotland,” says Matt.

“It had the cult of Saint Andrew – the relics supposedly that people from all over the British Isles and further afield came to see and pay homage to.

“It had the seat of the bishop and at this time the archbishop of Scotland.

“The church also had its own court system with St Andrews at the centre.

“But that’s also one of the reasons why Scotland’s first university at St Andrews (founded in 1411-13) was established because it was linked to the cathedral.

“It was founded by the Bishop of St Andrews, Bishop Wardlaw, and many of the students would have been preparing to go into the church to become clergymen.”

What Hardyng wanted to emphasise to the English king, says Matt, was that “this is a rich and flourishing kingdom – you really want to invade this place”.

Suggested invasion route

The chronicle itself included a suggested plan of attack and route for invading Scotland.

“The idea was that they would get themselves to Falkland and go south-east to Dysart and then on to St Andrews and then to Kinghorn,” says Matt.

“They said they could ‘feed the fleet’ at Kinghorn.

“It seems an odd route to me, but that’s what Hardyng said!”

Dr Claire Breay, Head of Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts at the British Library, told The Courier they were “thrilled” to be loaning the Hardyng Map of Scotland to the Wardlaw Museum.

“The map was compiled by John Hardyng, who was born in 1377 or 1378, probably in Northumberland, and lived most of his life during the Hundred Years’ War between England and France,” she says.

“He joined the household of Henry Percy (‘Hotspur’) when he was 12 years old, and fought for the Percys in Anglo-Scottish border battles.

“He also served in France during the reign of Henry V, who sent him on a spying mission to Scotland in 1418.

“Hardyng is best known for his verse Chronicle of the history of Britain, in which he set out his fervent belief in the right of English kings to rule over Scotland.

“He was so determined to prove his case that he forged a series of documents purporting to provide corroborating historical evidence.”

Presented to King Henry VI

Dr Breay explained how in 1457, Hardyng presented the first version of his Chronicle to King Henry VI of England, as part of his failed attempt to instigate an invasion of Scotland.

The Chronicle is accompanied by this colourful map, spread across two pages, which depicts a very rectangular Scotland with west at the top.

“Hardyng doubtless drew on his earlier years of reconnaissance in Scotland in compiling his map,” she adds.

“It includes much more topographical information and many more towns right across Scotland than in earlier surviving maps.

“The castles and walls of the towns are remarkably varied, while at Glasgow and Dunfermline the churches are drawn instead.

“The rivers are very clearly marked, with the River Forth, bridged at Stirling, running from top to bottom, and almost cutting the kingdom in two.

“The level of detail, which Hardyng hoped would help an invading army, is strikingly different from earlier maps of Scotland.”

She adds, however, that it’s not known whether King Henry VI of England ever read Hardyng’s Chronicle or saw the map.

It’s also not known what Hardyng’s reaction was when the invasion he was advocating didn’t happen.

Hardyng went on to produce a revised version of the Chronicle which he completed in the 1460s, when he was in his 80s.

It’s clear therefore that he never gave up trying to make his case to the king of England.

Questions about Scotland’s future

Principal and Vice-Chancellor of St Andrews University, Professor Sally Mapstone, is an expert in Medieval and Renaissance Scottish literature.

As a medievalist, she is also delighted to welcome Hardyng’s map to St Andrews.

“Hardyng’s map provides important context to the dynamic relationship between Scotland and England throughout the ages,” says Professor Mapstone.

“It has broad appeal not only to those studying here in St Andrews, but also to anyone interested in the ways in which Scotland’s geographical, political and cultural conditions have changed over centuries.

“Every map tells a story and I look forward to the discussion, debate and reflection that will be sparked at this critical juncture in Scotland’s future while the map is on display at the Wardlaw Museum.”

Museum visitors

Visitors to the Wardlaw Museum have the chance to pit their wits against a 15th-century spy as part of an escape room experience accompanying the map.

Participants are asked to crack clues that will help them capture John Hardyng on his Scottish reconnaissance mission, before he escapes to England.

Cult, Church, City: Medieval St Andrews is an exhibition created by Professor Michael Brown and Dr Bess Rhodes, world experts in the town during this period.

On display are items that have never before been seen together, including a brightly coloured bishop’s robe, on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Treasures on Tour: John Hardyng’s Map of Scotland and Cult, Church, City: Medieval St Andrews runs at the Wardlaw Museum until Sunday July 3 2022. Entry is free.

John Hardyng’s Map of Scotland is part of the British Library’s Treasures on Tour programme and is supported by the Helen Hamlyn Trust.