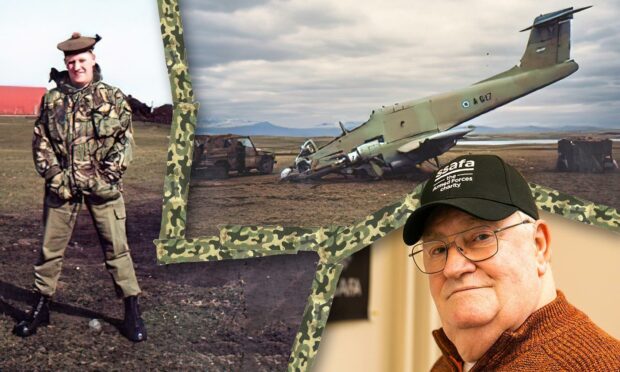

Army veteran Jim Laughlin was on the high seas, en route to join the Falklands War, when the ceasefire was declared.

But rather than head home, the Fifer and his colleagues from the Queen’s Own Highlanders continued their horrendous 8,000-mile journey to the South Atlantic.

And they spent six long months carrying out gruelling work to clean up the islands and help locals return to normal life.

The battalion was eventually awarded the Wilkinson Sword of Peace – presented to members of the armed forces who go above and beyond in their work for the community.

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the outbreak of the undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom.

And Jim, from Cowdenbeath, has told us his remarkable story.

He says: “It’s an experience I’ll never, ever forget.”

The terrible journey into war

He was a 31-year-old sergeant in the anti-tank platoon when Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands, on April 2 1982.

And the Queen’s Own Highlanders formed part of the third tranche of the armed forces to make their way to the conflict zone.

Jim, who is now 71 and a grandfather of two, had served for 12 years and completed tours of Northern Ireland, so knew the dangers he faced.

And he put wife Arlyne, daughter Claire, two, and six-month-old son Gordon on a train to Aberdeen to be with family in case the worst happened.

However, the troops faced a huge challenge before they even arrived at the British territory – the most awful journey of their lives.

It took around a fortnight and by the time they arrived on Ascension Island, everyone was as sick as a dog.

Where the southern trade winds met the northern trade winds it was ferocious.”

Jim Laughlin.

Jim recalls: “It was on a car ferry normally used on the English channel. It wasn’t designed for a journey like that.

“The boat was painted black and all the windows were blacked out.

“Where the southern trade winds met the northern trade winds it was ferocious.

“I was stuck in my bed for three days and couldn’t move.”

Although the war was still being fought when they left Plymouth, news of the ceasefire reached them during their journey.

When they arrived they became the first resident battalion, tasked with cleaning up the battle-scarred islands.

‘They might be the enemy, but they’re people’

The Queens Own Highlanders were based at Fox Bay, the second largest settlement on West Falkland.

The Argentinians had surrendered and left the island. And there was no need for the anti-tank weapons Jim was trained to use.

However, the battalion’s work was still very difficult and traumatic.

Bodies still lay where they had fallen in the heat of war and were covered in snow and ice.

And Jim, along with the 20 men under his command, had to dig them up and ensure they received a proper burial.

“There were British Paras but also Argentinians, all very young,” he said.

“They might be the enemy but they’re people and had to be treated properly.

“Then we had to move the bodies of the Paras and have them re-interred in the cemetery in Stanley – or, if the families preferred, brought back to the UK.

“That was a thoroughly unpleasant job.”

The sheep were blowing up the landmines

Despite the ceasefire, the islands were strewn with landmines.

Weapons dropped as the enemy fled were taken and stored by locals, terrified they would return.

Part of Jim’s role was to round-up the missing kit and clear the landmines – a job that was far easier said than done.

The Argentinians hadn’t properly marked the mines and had placed them in shifting sands.

It meant a mine spotted in the morning could have moved by the afternoon.

“If we knew there was a mine we put a barbed wire fence round it and a sign on it,” said Jim.

“But when the first of our Land Rovers blew up we knew they were moving.

“Sometimes, the only way we knew where they were was when sheep walked over them and detonated them.”

Tracking down the weapons stashed by locals also led to some astonishing incidents.

“We found a barn that was like an Arnold Clark garage, full of Mercedes 4x4s used by the Argentinians,” said Jim.

“One evening a local man fell down a hole with a bottle of whisky and he was firing to get someone to rescue him,

“We almost launched a full assault!”

Helping Falkland Islanders return to normal life

After a conflict lasting 74 days, services on the Falkland Islands were severely disrupted.

There was little in the way of fresh food and troops were living on basic Army rations.

And locals too were suffering.

The Queens Own Highlanders were stationed there long after the war ended to help islanders return to normal life.

“The Army postal service brought in groceries and fuel,” said Jim.

“Their electricity was supplied by generators, many of which were broken so we brought in mechanics to fix them.

“We had a medic who provided first aid and we fixed the boats.

“When things started to stabilise boredom set in so some of the guys learned to shear sheep. I’ve never seen so many sheep!”

Battalion had to argue for their medal because they ‘didn’t fight’

The troops’ efforts were rewarded with the Wilkinson Sword of Peace.

And the accolade almost made up for the fact the Queen’s Own Highlanders were initially denied the South Atlantic Medal – a campaign medal awarded for service in the Falklands War.

Jim said: “We weren’t getting it because we didn’t fight. The war was over when we got there.

“We were very angry about it and argued the threat to life and limb was just as high, or higher, during that period.”

Margaret Thatcher’s government did eventually have a change of heart and awarded it in recognition of their work.

In all, Jim earned four medals for his service, which included eight tours in Northern Ireland and a spell in the first Gulf War.

He left the Army in 1992 suffering from post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following his experiences in the Gulf.

And then followed a long civilian career in logistics, working for Littlewoods.

‘The toughest thing I’ve ever done’

He now volunteers for the armed forces charity SSAFA at its office in Kirkcaldy.

It provides lifelong support to servicemen, veterans and their families.

And Jim has helped many people access financial benefits and help for PTSD.

The 40th anniversary of the Falklands War has given him pause for thought.

And he has been reminiscing about his time in the Falkland Islands.

“It was a really tough experience,” he said.

“I’d been in Northern Ireland but it was nothing like that.

“Even the weather – it was like Scotland on steroids with all the snow and rain.

“Physically, it’s the toughest thing I’ve ever done.”