What was the psychological impact on the men of the infamous Arctic convoys? Michael Alexander speaks to retired St Andrews psychologist Dr Martin Campbell who considers the trauma and experimental psychiatric treatments they were exposed to in a new book.

They risked their lives on what Churchill described as “the worst journey in the world”.

The heroes of the Arctic convoys ran the gauntlet of German warplanes and U-boats to keep their Soviet Union allies supplied on the Eastern Front.

In recent years, Russia has even awarded commemorative medals to British veterans to acknowledge its gratitude to the surviving sailors, more than 3,000 of whose comrades were killed.

But what was the psychological impact on the men of the Arctic convoys?

And what methods did the Royal Navy use to try and treat traumatised sailors at a time when psychiatry was less developed than it is today?

New book

The issues provide a backdrop to a new book by North East Fife-based writer Dr Martin Campbell.

The retired University of St Andrews senior psychology lecturer has written a psychological thriller called Sailor’s Heart.

The book is set in 1942 and tells the tales of three men fighting for their country in the Arctic convoys of World War Two.

However, they are undeservedly branded as cowards and subjected to experimental psychiatry which reduces them to being both military and social outcasts.

Perhaps the most sobering part of the entire book, says Martin, is the realisation that the issues are not fiction.

“This is not a documentary of my personal work,” says Martin.

“It is though, a tale of men who underwent the most horrific psychological pressures, often placed upon them by those who were supposed to be on the same side.

“They are forced into an adventure that none of them expected and certainly did not want.

“I did not set out to shock but to simply tell it the way it was and for some people, still is.”

Combined interests

As an academic, Martin wrote and published over 30 psychology articles and books.

With a primary interest in additional support needs and people with challenging behaviours, the Greenock-raised Stirling University psychology graduate taught children with additional support needs before “drifting into academia”.

He latterly worked three days a week as a senior lecturer in psychology at the University of St Andrews as well as two days a week working with health services in psychology practice.

However, having retired not long before the Covid-19 pandemic, the 65-year-old who lives in Ceres, now has more time to focus on another growing passion – the writing of novels.

Having published Bad Beat Hotel in 2016 – a novel about the dangers of playing poker –Sailor’s Heart combines his interest in the Arctic convoys with his knowledge of psychology.

“There’s two strands to Sailor’s Heart,” says Martin in an interview with The Courier.

“One part is the Arctic convoys which I’d always had an interest in.

“The other part was this facility set up by the British Admiralty at Kielder in the north of England.

“I’d read about both of them but had to think of a way of linking them.

“Because a lot of the men from the Arctic convoys suffered mental breakdowns, the navy eventually decided they needed to try something different to ‘recycle’ men back into battle because at one point there was 1% of the entire naval personnel being referred to psycho-neurosis as it was called then.”

‘Rehabilitation centre’

Martin didn’t know anything about the Royal Navy establishment that existed at Kielder during the Second World War.

That all changed when, one day, while visiting the forest and dam, an angler said to him: “You know what’s down there under that water? That’s where they did those things to those sailors!”

Martin had no idea what the man was talking about.

But when he went away and investigated, he discovered that from 1942 to 1945, before the dam flooded the valley, it had been the setting for HMS Standard – a shore-based assessment and rehabilitation centre for naval personnel diagnosed with personality disorders.

Men posted to the base fell into three categories; those with low morale, men of temperamental instability and malingers.

The aim was to return these men not necessarily to active service but to some form of effective service.

“It was a navy psychiatric residential unit for navy personnel who were considered not fit for service but possibly “recyclable” given the right sort of treatment,” explains Martin.

“They set up this place that gave psychiatrists that were working there a bit of a free reign to try out new stuff to see what would work to try and get men to a state where they could be put back on ships or be put back on shore duties.

“That was the bones of the idea for the book. Then I had to create some characters to make it work.

“I went into naval records. I went into psychology papers, did a fair bit of research and tried to base the book on true events.”

Impact of the Arctic convoys

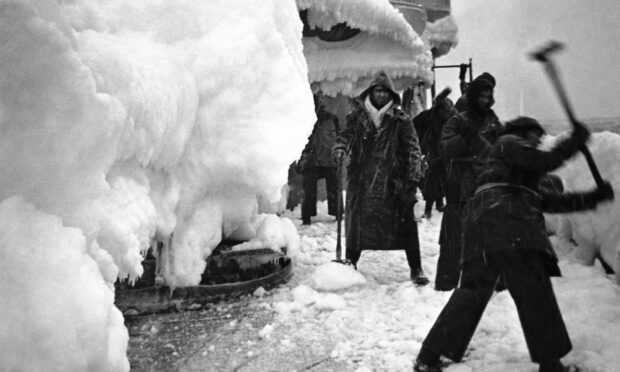

The Arctic convoys transported four million tonnes of supplies and munitions to Russia between 1941 and 1945.

A total of 78 convoys braved sub-zero temperatures and the German armed forces to get war supplies to the Soviet Union.

The British Merchant Navy along with Russian, US, Canadian, Norwegian and Dutch merchant fleets were involved.

By May 1945, the Arctic route had claimed 104 merchant and 16 military vessels.

More than 3,000 Allied seamen lost their lives to the freezing conditions and attacks during the trips to ports in the Arctic Circle.

But were the psychological pressures that faced the men of the Arctic convoys very different to what faced military in other theatres of war?

“That’s a really good question,” says Martin.

“They were different principally because – there were a few factors.

“The likelihood of severe weather, the freezing conditions – a lot of men actually died on watch.

“The constant threat of attack by air by submarine by surface forces from the Germans, and I guess the worst one was the unpredictability of when the battle would start and when it would stop because they were sitting targets out there and they didn’t know where the next attack was going to come.

“Psychologically that’s worse because unpredictable shock or unpredictable trauma is worse than predictable trauma.

“The other factor was the navy decided to put all of their psychiatrists on shore-based services.

“They didn’t have anybody on the ships to identify when men were breaking, so if they were still able to walk upright and do their duties, nobody noticed, whereas in the army services, perhaps in the air force as well, there was more services to detect when things were going wrong and men were breaking down.”

‘Disturbing’ losses overboard

Records show that around 3000 men died on the Arctic convoys.

There are also records of men who were discharged from ships after breaking down “in the most obvious ways”.

Perhaps what’s more disturbing, however, is the records of the men who were “lost overboard”.

“The suspicion is,” says Martin, “that some of those men, perhaps a significant number, took their own lives because of the stresses they were under.

“Digging into naval records it’s really difficult to get a break down of how many said ‘I can’t go on any more’, or how many deserted on shore leave which was another factor.”

Martin says the methods used at Kielder were fairly cutting edge.

They used the experiences of “shell shock” from the First World War to treat trauma. They used a lot of physical exercise and outdoor activities against a backdrop of naval discipline.

However, records of actual medical treatments are “more guarded”.

Controversial

Martin says there’s little evidence that anything learned at the camp added to innovations around psychiatric treatment.

“I guess you also have to take in the social context of how we view men with PTSD nowadays and how they viewed men who weren’t able to fight in those days,” he says.

“There was a lot more stigma then. If you bailed out, if you didn’t do what you were supposed to do for your country, you were seen as either a malingerer, a coward or a poltroon – you weren’t regarded as someone who was worthy.

“Nowadays there’s far more supportive services whereas then it was unlikely they would take a supportive view.”

During his initial research, Martin looked back to the first naval psychiatric facility in 1784 at Haslar Hospital in Gosport.

Times have changed since the “primitive” therapies of those days.

However, with Ukraine reminding us today about the horrors of war, Martin still feels society at large “doesn’t have a handle on how to treat soldiers, sailors or air force men who break down in war.”

“There’s still an ambivalence to whether break downs should be regarded positively or negatively,” he says.

“Is it something to be regarded as mental illness? Or is it a wonder more men don’t break down rather than the fact relatively few do? There’s still a lot of stigma.”

Where is the book available?

Sailor’s Heart is available from most bookshops and online, priced £11.95. ISBN: 9781527254824