A former miner believes that a failed Fife pit could be reopened again.

Jim Parker, who formed part of the management team at the Rothes Colliery on the outskirts of Thornton, believes that reopening the former “superpit” could be economically viable.

“The Rothes”, as it was known, was originally opened in 1957 but closed after just five years following concerns over flooding.

Today it is regarded in some quarters as one of the country’s greatest ever industrial failures.

However, claiming that fears of flooding were exaggerated, Mr Parker says that reopening the Rothes is not beyond the realms of possibility.

“Rothes was wet when we sunk the shafts but the contractors did a great job of sealing them off,” he said.

“The pit pumped out less water than Seafield in Kirkcaldy.

“There is nothing commercially to stop the reopening of the Rothes Colliery, even today.

“There are two shafts that were excavated and they were strong because money was no object when they were established.

“The tunnels will stand for another 100 years, so if the price is right then it is definitely worthwhile doing.”

More than 2,000 miners were expected to find employment at the Rothes Colliery, with many having moved from the west coast of Scotland to take up residence in the New Town of Glenrothes, which was established to cope with the expected influx of workers.

The Queen formally opened the pit in 1958, an example of just how symbolically important the new mine was considered at the time.

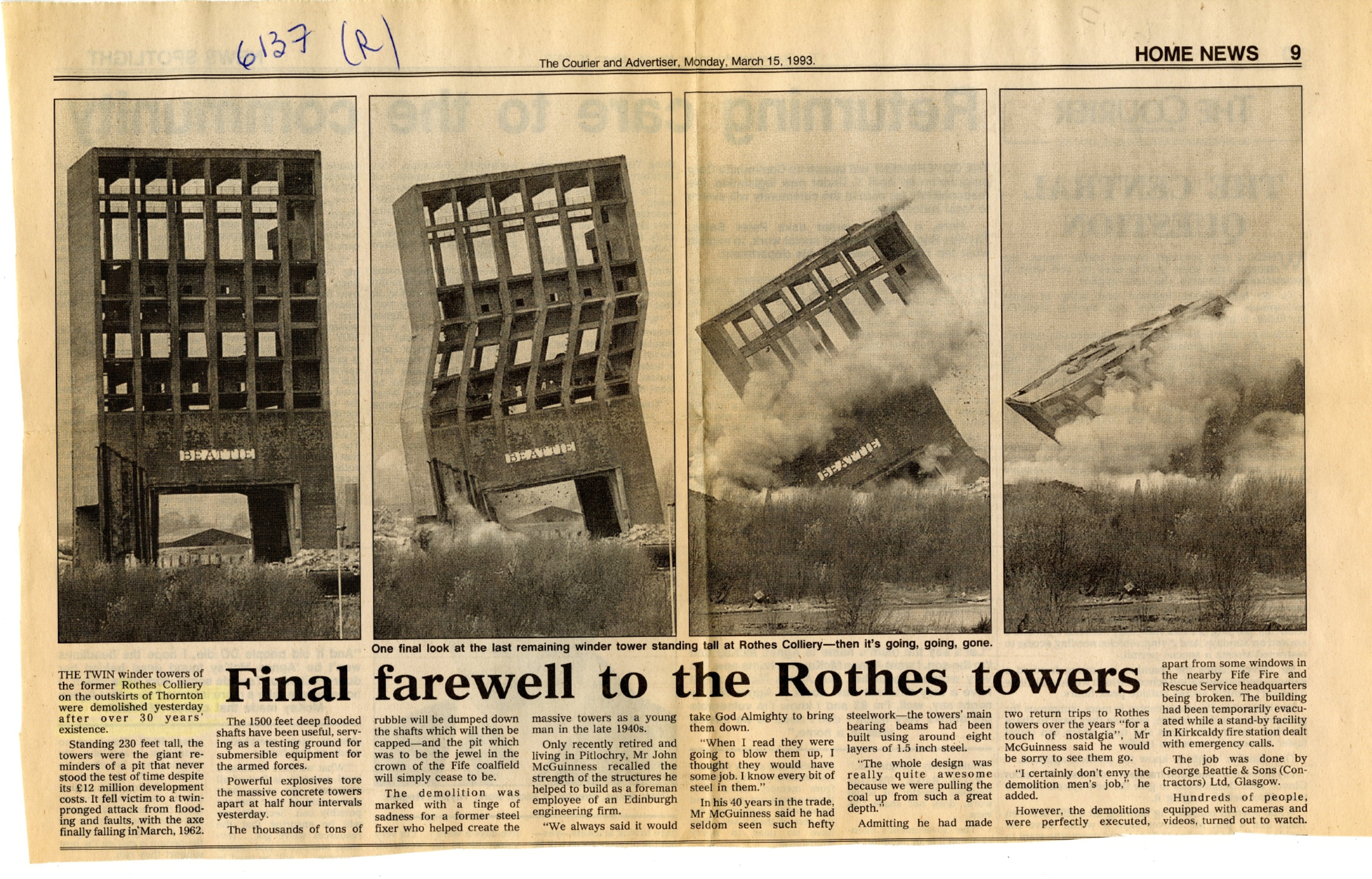

But its lifespan was short, and the last visible trace of the pit — its unusual rectangular winding towers — were demolished in 1993.

However, with energy prices rising, Mr Parker has long advocated a return to coal mining in Britain as a means of fuelling the country into the future.

Despite environmental concerns, industry continues to burn coal, with Mr Parker arguing that British pits could be reopened to meet the world’s energy needs.

With the cost of excavating new mines thought to be financially restrictive and rich seams of coal spreading for miles, the former Rothes Colliery could provide employment and a source of energy, should coal become a fashionable fuel once again.

Acknowledging that there were massive inefficiencies at the superpit in its day, Mr Parker said that the showpiece mine became an easy target for the Conservative government of the time, with the appointment of Alf Robens as chair of the National Coal Board ultimately prompting the axe to fall as part of a host of cuts to the industry.

“Robens said that he was going to revolutionise the industry and had to close mines to set an example to the workers,” claims Mr Parker.

“He did it to show he meant business and Rothes was one of those sacrificed.”

Rothes Colliery: A short history of a “superpit”

It was hailed as the greatest coal mine in Europe and a technological marvel that would sustain the hopes and dreams of an entire town.

Rothes Colliery began to take shape on the banks of the River Ore in the late 1940’s.

Developed at a cost of £12 million, the pit was expected to produce 5,000 tonnes of coal a day for well over a century.

Its two angular wheelhouses, like nothing else seen before, stood like sentries over the pithead and dominated the skyline of what was to become Glenrothes, the very town created to house the workers of “The Rothes”.

But the twin towers, designed as symbols of a modern, confident, post-war Britain, were soon to become a sore reminder of one of the biggest industrial failures in the country’s history.

From the very start there were problems, with the mine affected by a strike on its first day of operation in 1957.

Despite an official opening by a young Queen Elizabeth II a year later, in which she became the first female monarch to go down a pit, the problems that were to blight the site had already become apparent.

The 1,300 miners — just half of the original estimated workforce — found themselves fighting a losing battle against flooding and geological faults, with the sinking of shafts eventually cancelled due to the abundant problems.

With coal only able to be mined from the upper levels, the clock was already ticking for the so-called “superpit”, with the National Coal Board deciding to bring the axe down in March 1962.

The site, however, did find some use following the pit closure, with the 1500-feet flooded shafts utilised by Britain’s armed forces as a test site for submersible equipment, while the fire service also used the shafts as a practice site for underground rescues.