The recently released Dunkirk movie has inspired former journalist Ian Nimmo, of Fife, to write down his late father’s first-hand account of being evacuated from the beaches. Michael Alexander reports.

It has been described as one of the greatest war films ever made by some, and been blasted for its historical inaccuracies by others.

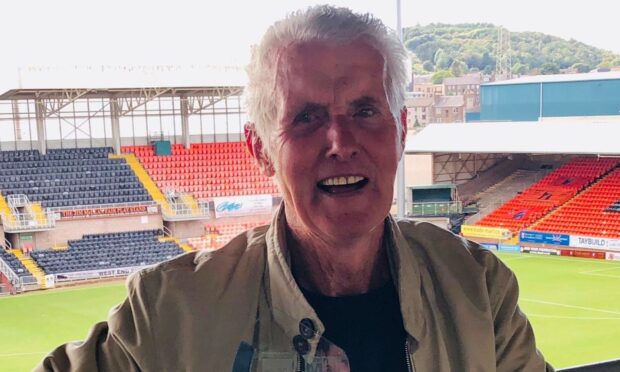

But for Fife man Ian Nimmo, Christopher Nolan’s recently released movie, Dunkirk, has proved to be a timely reminder of how his own father became one of the last soldiers to be evacuated off the French beach when a fleet of small ships went to the aid of the British Army between May 26 and June 4 1940.

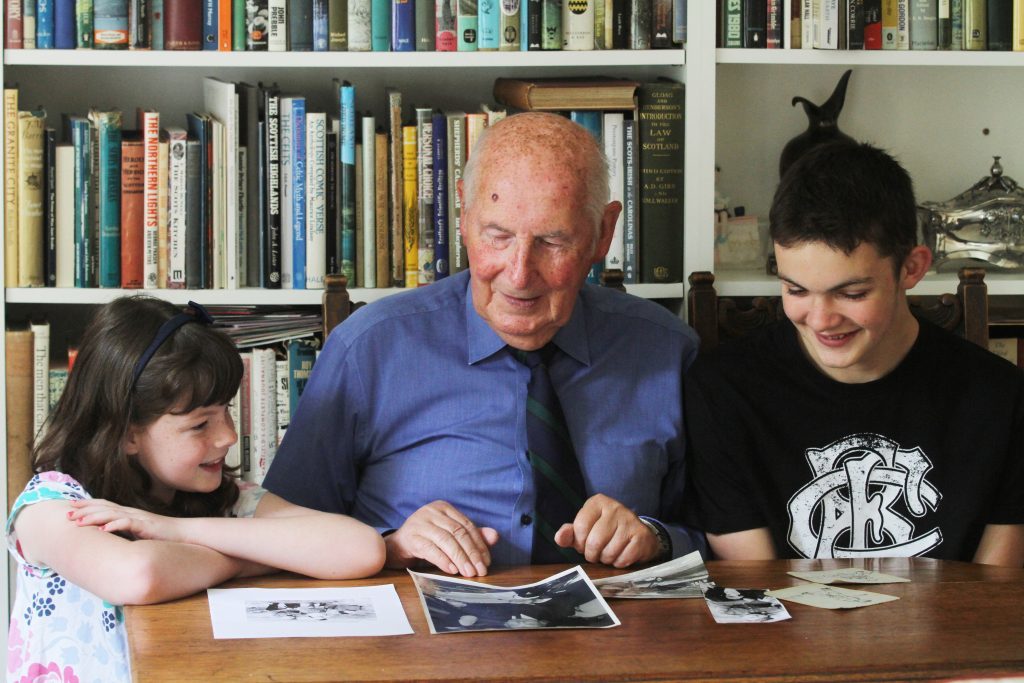

Ian, a former newspaper editor who now lives in Freuchie, was just four-years-old when his father, Sergeant Joe Nimmo, was yanked back into service with the Royal Scots Fusiliers just before the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939.

The youngster and his family had been picnicking close to their home at Rumbling Bridge, Perthshire, when a policeman on his bike stopped them on the Amulree Road outside Dunkeld and asked his father if his name was Nimmo.

It was an instruction for the regular soldier to re-join his regiment in Ayr and when young Ian awoke the next morning, his father was gone.

The family later discovered he was “somewhere in France or it could be Belgium” with the British Expeditionary Force.

But by the time of Dunkirk in May 1940, he was one of the last men standing on the beaches under enemy fire.

“It all came flooding back after watching the graphic new Dunkirk film, and I have been reliving my father’s own dramatic tale as he and his detachment of Fusiliers made a fighting withdrawal to those same shelled, bombed and air-straffed beaches,” explained Ian, now 83.

“My dad was a veteran of the Fusiliers in the First World War, the White Russian Revolution of 1919, the Sean Fein problems in Ireland, and then a seven-year tour of duty on the North West Frontier of India.

“What happened at Dunkirk, however, seemed to have eclipsed many of his other war experiences.”

After the war, Joe, who died in 1983 aged 82, would share some of his experiences.

But only as time has gone on does Ian wish he had listened more carefully to his stories, to dates, and to names of towns and villages they fought through to reach the Dunkirk beach.

The lack of detail, however, has not stopped Ian from writing down what he does know after seeing the Dunkirk movie in Edinburgh.

And now the author of 10 other books, who himself served with the Fusiliers during his National Service days, is considering writing his father’s experiences up as a book.

“The Fusiliers had set themselves up in a deserted farmhouse, but supplies were running short, communications breaking down, and shells falling,” explained Ian.

“My dad commandeered an ambulance and, with Fusiliers Grieves and O’Neill for support, scavenged food from abandoned villages for the men.

“The three were piling tins into the ambulance, when German infantry entered the other end of the street and opened fire.

“They sped down a narrow road, turned a sharp bend and a tank barred their way. A long skid of clamped brakes before they recognised it was British.

“It was from the tank commander he learned Belgium was out of the war and the French were struggling.

“The word is head for the coast. A place called Dunkirk. They’ll lift you back to Blighty from there. Our orders are to slow up the German advance as best we can.”

The Fusiliers put up a roadblock to manage refugees but the task was hopeless.

It was being swamped by the harrowing sight of the very young, the elderly, the ill, the exhausted trudging with what belongings they could carry, discarding some as they went.

“Dunkirk was well ablaze when they arrived, “ explained Ian, “with exposed troops on the open beach waiting evacuation with shells falling, screaming stukas bombing.

Joe was reported missing when he went searching for two missing colleagues. The building where he had been standing was destroyed in a stuka raid.

But he and his comrades survived, only to find that when they reached the beach the Fusiliers had gone.

Wading into the sea, they were picked up by a small boat, taken out to a destroyer, and clambered aboard.

Joe and the exhausted survivors were whisked off to Lyme Regis in Dorset, where they joined thousands of troops from many different regiments already sprawled in deep sleep.

Meanwhile, back in Dunkeld, Ian’s mother received a telegram to say her husband – his dad- was safe and armed with a week’s leave. He returned by bus to a heroes’ welcome.

“My father’s Dunkirk story will be similar to thousands of others who were in that historic rescue from the jaws of a military disaster,” added Ian, who still has his dad’s Dunkirk glengarry and keeps it next to his own from 16 years later.

“Like me, the new film will have stirred memories of those few who still have links to those dire days. Like me, they will recognise heroes and be proud.”