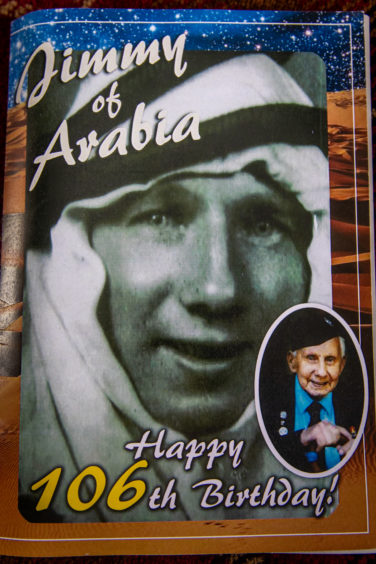

With Armed Forces Week 2019 upon us, Michael Alexander meets legendary Fife Desert Rat Jimmy Sinclair, who is now in his 107th year.

He is the oldest surviving Desert Rat who retains unlikely friendships with the family of the late German general Erwin Rommel and receives regular letters and photographs from Prince Charles’ wife Camilla Duchess of Cornwall.

But while Fife man Jimmy Sinclair, who turns 107 in August, is happy to talk at length about his experiences at the infamous Siege of Tobruk, the Battle of El Alamein, and assaults on Monte Cassino in Italy, he still refuses to wear his medals out of solidarity for the “good mates” he lost.

Jimmy, who battled Nazi forces when he served as a gunner with the elite Chestnut Troop of the 7th Armoured Division in Africa, was part of the effort to defeat Field Marshall Rommel in the Egyptian desert in 1942.

But far from glorifying war, the centenarian “feels sorry for the fallen” on both sides and to this day refuses to think of the average Second World War German soldier as being the enemy.

“It’s a pity it all happened,” he reflects when asked about the war. “We didn’t treat the Germans as enemies. They were combatants in battle. Most of them didn’t want to be there either!”

Regarded by many as a national treasure, Jimmy is in fine fettle and looking remarkably well when The Courier arrives at his ground floor flat in Kirkcaldy where he’s helped on a day-to-day basis by his carer Archie Howie and receives regular support from Fife’s lifeline home care service.

The widowed father-of-two and grandfather-of-three laughs when asked what the secret is to living to a ripe age.

“I tell the folks a joke,” he says with a wry smile. “The Scotsman went to the doctor for a check-up and the doctor said ‘do you drink?’ No. ‘Do you smoke?’ No. ‘Do you go with the women?’ No. Doctor says, ‘you’re better dead!’”

Jimmy, who wears hearing aids, admits he likes a “wee dram of Johnnie Walker whisky” as a nightcap.

But he says the elixir of life for him is that he has “never smoked and never drunk”.

“When I was at school I tried one cigarette and got sick and never looked back,” he says.

Born in Ladybank on August 18, 1912, Jimmy was brought up by his grandparents in the neighbouring hamlet of Giffordtown after his mother died in child birth.

When his father, who re-married, got a job as a stoker at the Abernethy gas works, he joined him there.

Leaving school to become a slater, Jimmy joined the Territorial Army and served with the then Newburgh platoon of the Black Watch from 1931 to 1934.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, not long after he was married, he joined up with the Royal Artillery in Perth and was sent to the south of England to train with the Royal Horse Artillery.

Jimmy’s four years in the desert began when he joined 3000 troops aboard the requisitioned ocean liner Britannic – embarking on a six-week voyage from Liverpool to Cairo via Sierra Leone and Cape Town.

“We couldn’t use the Mediterranean because it was full of Gerry submarines,” he explains.

Jimmy laughs when he recalls how he and a friend went ashore in Cape Town for a couple of days and bumped into a man who it turned out worked with his grandfather at the Ladybank malt barns back home in Fife.

But he has mixed emotions when he recalls the Siege of Tobruk, which lasted for 241 days in 1941.

“One day we were in the Naafi,” he says. “We were living in a sandbank dug out and I put a piece of chocolate in the palm of my hand and showed it to my mate. I says ‘come and see this’. A rat came out between the sand bags and took the chocolate and went back in. A real desert rat on the palm of my hand! I once woke up to find a rat chewing my ear!

“But my mate fae Falkland got killed at Tobruk,” he adds reflectively.

“We were under fire from German 88s. We were firing 25 pounders. It lasted a long time.

“We came under fire from Stukas. They came over every day at dinner time but they got shot down because they were that slow at taking off.”

Jimmy recalls how at El Alamein, the British and Allies fooled the Germans’ aerial reconnaissance photographs by disguising columns of tanks as trucks, only to whip off the camouflage when the time came to open fire.

Then at Monte Cassino, where he was badly burned and spent eight weeks in an Italian hospital, he found himself as the driver for banking executive Hugo Baring of Baring Bank fame. “He was a proper gentleman and one of the bravest boys that ever come,” he says. “I kept in touch with him until he died.”

After the war, Jimmy, who played trombone in a band, served for two years with the Control Commission in Berlin.

He became friends with the Rommel family after meeting at a big concert in Aachen, Germany.

He met the wartime leader’s son Manfred, who was Lord Mayor of Stuttgart from 1975 to 1996, and stayed friends with him until he died from Parkinson’s aged 84 in 2013. He still receives letters from the widow.

However, it’s his friendship with Camilla Duchess of Cornwall – whose father was a Desert Rat – that’s perhaps best represented by the photos and cards he has on display in his living room.

They first met when he attended a Desert Rat reunion in Ipswich and she was chief patron.

He must have left an impression on her because she started writing. She sent him a book by her father Major Bruce Shand, a card when her brother Mark Shand died in New York in 2014 and he was invited to meet her and Prince Charles at Holyrood Palace on his 100th birthday.

“I said to him, ‘Your mum should be the first of Scotland and the second of England’ and he laughed and walked away – long ago I’d have had my throat cut!” he laughs.

He then met the royal couple again at the Caird Hall in Dundee a few years ago when Camilla came and sat next to him.

“She had no airs and graces – a lovely woman,” he adds.

Jimmy says you need a sense of humour to be 106, and he certainly has his fair share of “good answers” when he can’t quite remember details about some parts of his life.

But as he looks forward to having another “wee nip like Churchill” before he turns in for the night, and says farewell with a firm handshake, it’s the gratitude in his eyes for listening that’s most striking, and the contentment of a long life well spent.