In the second in an ongoing series looking at transforming travel for the better, we speak to world-renowned urban mobility expert Mikael Colville-Andersen about his trip to Dundee last year – and what he believes has gone wrong in the way we plan our cities and their streets.

Before he begins, cycling advocate Mikael Colville-Andersen wants to make it very clear that he has great affection for Dundee and Scotland as a whole.

“I thought it was amazing when I came out the train station,” he recalls of his visit to the city for a conference in January last year.

“I had time that afternoon and wanted to see the V&A. It was right there but first I had to figure out how to cross the street.

“I’ve worked in transport and it was like I’d gone back to 1952 – what a blast from the past.

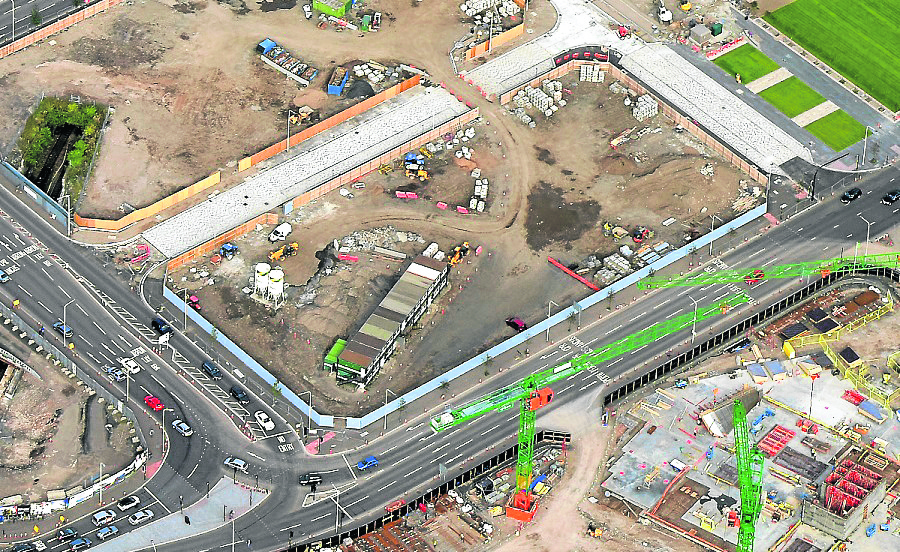

“The road was new, I could see it was new, and someone had just put that in. Brand new, but continuing what we all know doesn’t work. Think of all the money that is being spent on failed solutions.

“It was like so many other cities: nothing special transport-wise. I’d seen it all before.”

Ahh. Sunrise over Motordom. #Dundee #Scotland pic.twitter.com/d6lbheibcr

— Mikael Colville-Andersen (@colvilleandersn) January 23, 2019

The driving force behind “bicycle urbanism”, Canadian-Dutch architect Colville-Andersen is an outspoken critic of urban design that fails to consider active travel. He founded a consultancy, The Copenhagenize Design Company, in 2009 to promote bike-friendly infrastructure to city planners.

Now an independent consultant, he evangelises cycling as a normal, everyday mode of transport – without descending into the Lycra-clad, anti-car militant activism some associate with pedal-pushers – and explores this in The Life-Sized City, a Canadian documentary series about city design.

During his visit to Dundee, Colville-Andersen described the V&A as being “fenced in” by multiple pedestrian crossings and four-lane-wide carriageways which prioritised moving traffic over people.

“Dundee is making the same mistake, rather than learning from other cities,” he said at the time. “There’s more to it than building a V&A and some roads.”

The city’s cycling spokesman, Councillor Kevin Cordell, defended the city council’s approach following the expert’s visit, highlighting the installation of a cycle storage shed at the train station and the refurbished path at the Port of Dundee.

But Colville-Andersen believes cycling will not grow in popularity as long as roads like those newly built at the Waterfront prioritise cars above all else.

Subscriber-only video

Courier subscribers can watch our full interview with Mikael Colville-Anderson in which he describes the need to reshape our streets, calls driving “the new smoking”, explains why cycling is not about the ‘Spandex boys’ — and suggests Dundee’s traffic engineers and politicians need ‘a kick in the pants’

“I often say our traffic engineering is still stuck in the 1950s – we are still using the same models now as they did then,” he says, speaking from his home in Copenhagen.

“Imagine education or healthcare was still using models from the 1950s. We wouldn’t stand for that – so why do we stand for this?

“I like Dundee, it was a great city to spend time in, but the traffic was depressing. Your traffic engineers and politicians maybe need a kick in the pants.”

“Pornographic obsession”

A common problem for cities like Dundee is planners’ “pornographic obsession” with designing streets for cars and then “squeezing” cyclists in, Colville-Andersen says.

And more often than not, those cars are not being driven by people who even live in Dundee – meaning the city centre is being designed for outsiders, not those who fund its development through council tax.

Were the city to be designed to move around the people who live there, he argues, there would be economic, environmental and health benefits linked to better mobility, cleaner air and an urban centre that feels like it should be lived in, not travelled through.

Want to see better support for cycling? Click here to take part in our survey

“A couple of generations ago, after the war, we saw the car as the solution to moving people around. We put the blinkers on and pushed everybody else – bikes, trams, buses – aside and forgot all about them.

“Then we copy-pasted from the American transport system, and put traffic engineering on a pedestal. Traffic engineers are people who have a purpose in the way we design our cities, but we put them on a pedestal.

“We know after 100 years if you open a motorway or add an extra car lane you don’t improve traffic flow – you just make more space for cars, and if you do that you get more cars.

“Who is that for?” he asks. “The people who commute into Dundee?”

Yeah… uh… so… not a lot to report on the subject of #bicycle #urbansim in and around #Dundee. Bike racks at a station near the city. Some #bikeshare bikes at the station. Yep… #MicDrop pic.twitter.com/dI56Mod0Bi

— Mikael Colville-Andersen (@colvilleandersn) January 22, 2019

“We need to recalibrate and reboot. At 7pm, I can play frisbee in the street outside my apartment as everyone has gone home to the suburbs, to a different area.

“(The suburbs are) a different municipality so they don’t pay tax on the asphalt my taxpayer money has provided for it. I don’t think that’s very fair in an urban democracy.

“We’ve got two million people in the metro area and all the people who park their cars here don’t even live here – they come here to work, then they drive home and shop.

“Yes, people have cars, but they don’t live here, so shut up.

“This isn’t about being anti-car, it’s about being pro-city, and those things don’t dance together any more.”

“We can start tomorrow”

Even before Covid-19 emptied the world’s roads of traffic, a number of cities across the globe have been working to free up space for cars – and Colville-Andersen’s home city of Copenhagen has led the way.

Cycling underwent a renaissance in the Danish city in the 1980s after falling out of favour during the early car boom. Cyclists resisted city planners’ suggestions to use back-streets instead of the main roads – and before long, local government capitulated to pressure and free-wheeling became the norm.

Today, 41% of journeys in the city are made by bike, with families and even professional couriers travelling by bicycle. Traffic lights often prioritise cyclists, meaning the fastest way across the city is on two wheels. In all, the city has around 220 miles of segregated cycle lanes, and just 14 miles of the painted lanes favoured in UK cities.

City chiefs have even begun constructing a network of “Super Bikeways”: mini-motorways linking Copenhagen with its suburbs to encourage commuting by bike.

Colville-Andersen sees no reason why other cities couldn’t follow suit: why Dundee couldn’t have bike-first traffic lights, segregated cycle lanes, and car-free routes linking the city centre with suburban areas like Fintry and Lochee.

Lockdown has presented the perfect opportunity for the city to experiment as Copenhagen did decades before – and such an opportunity may never come again.

“Everything we need to improve transport has already been invented and can be employed starting tomorrow,” he says.

“Many cities around the world are using this opportunity to do some quick and totally temporary infrastructural change. It’s been the most amazing thing. We’ve seen some unlikely suspects coming out the blocks here and doing interesting changes.

“Once you see the changes, you can’t unsee them. In Milan, they’ve already decided they’re keeping what they’ve put in place, and they aren’t small changes.

“These are global cities, taking the matter into their own hands, and people are out enjoying the roads, taking this space back. It’ll be interesting to see which cities keep (their temporary lockdown changes).”

We're seeing this all over #Copenhagen. Cafes and bars are taking advantage of the loosened rules from the City about using public space for tables and chairs. Here, three parking spots have been redemocratised. #COVID19 pic.twitter.com/LMlHctBhYn

— Mikael Colville-Andersen (@colvilleandersn) June 5, 2020

Be-spoke design

So how does Dundee do better? To Colville-Andersen, designing city streets isn’t a matter of how many cars you can move – but how many people. Modern urban spaces aren’t even being “designed” to be enjoyed, by his reckoning, but soullessly “engineered” to move traffic.

What works best in cities like his own Copenhagen, he argues, boils down to two ideals: making cycling the best option, and democratising it to make it feel less exclusive.

“Here, cycling is quick,” he explains.

“It’s the fastest way from A to B in the city. That’s all people want. If you make the bike the fastest way from A to B, combine it with public transport and make people feel safe, then people will ride.

“I feel like driving is the new smoking. We didn’t consult smokers when we brought in anti-smoking laws – it’s the same with motoring. Public health is important, where our children aren’t breathing fumes every day.”

Likewise, he shuns the idea of cycling as a hardcore hobby. Indeed, the first photograph he took that inspired the Copenhagenize movement was of a woman cycling in a long skirt. On his Flickr profile, he regularly shares photos of casually dressed teenagers, adults and entire families moving through the city by bicycle.

“It doesn’t matter what the bike is, but when you get out on the streets in the UK the only people you see are the spandex guys. You don’t see yourself.

“All we have to do is reallocate the space, take away the space we have given to cars. They’ve only had it for 70 years, and we have 7,000 years of good urban experience. It’s time to go back to the future.

“That takes political will, but we see cities that are just doing it. And if we’re going to have a financial crisis again, which is possible, we’ll see an uptake in cycling. This is the time to make a choice: are you planning for the next 100 years of positive urban life or ad nauseum doing what we know fails?

“I’m not talking about saving a polar bear, I don’t give a damn about the spandex guys. I’m talking about regular cities and making them better places. Cities are for everybody.”

There is strong evidence to back up what Colville-Andersen says.

Paris has added 50 kilometres (31 miles) of coronapistes, or corona cycle lanes, as people try to avoid the Metro due to Covid-19. The French capital has already committed to removing 72% of its on-street parking to make those lanes possible.

In Milan, city bosses have pledged to make 35 kilometres (21 miles) of street more accessible to pedestrians and cyclists post-lockdown.

In Dundee, no such commitment has yet emerged, and like birds returning home after winter, the cars are beginning to line the Waterfront once again.

Our cycling survey

Over the coming days we will hear what local, national and international experts believe needs doing to keep people on their bikes during and after lockdown – and give the council their chance to respond in turn.

We also want to know what you think about cycling where you live, whether in Dundee, Angus or Fife. Are you a seasoned rider enjoying seeing others get in the saddle, or a new member of the cycling club taking to the roads for the first time?

Complete our survey and share it with your friends so we can put together a complete picture of cycling in Tayside.

If you have anything further you’d like to contribute to our story, email jbrady@dctmedia.co.uk with pictures, videos and anything else you’d be happy to share.