As the 140th anniversary of the Tay Bridge Disaster is remembered in Dundee and Fife, Michael Alexander discovers the human impact of the tragedy is still being felt to this day.

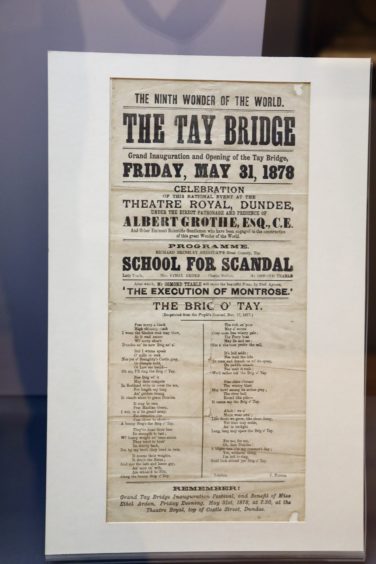

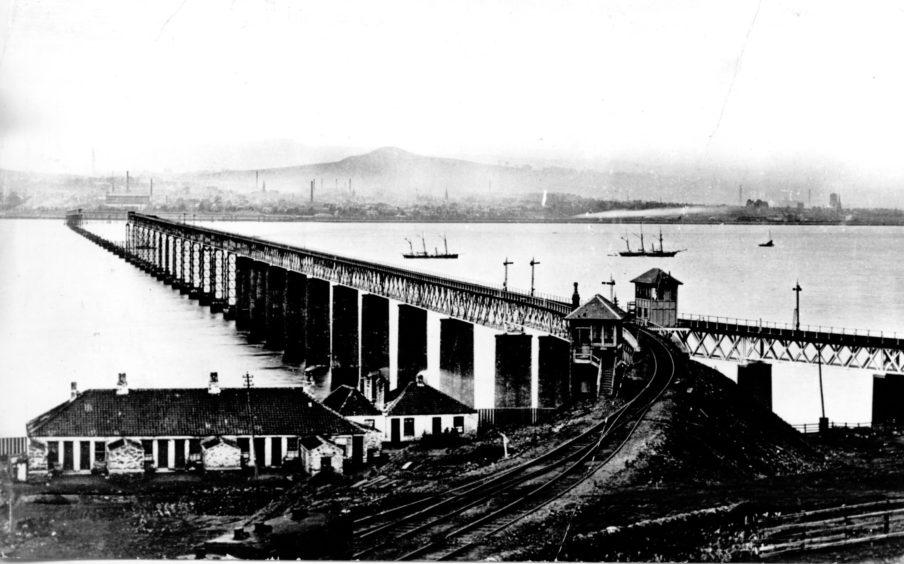

When the grand inauguration and opening of the Tay Bridge took place on Friday May 31, 1878, it was hailed by Victorian society as the “ninth wonder of the world”.

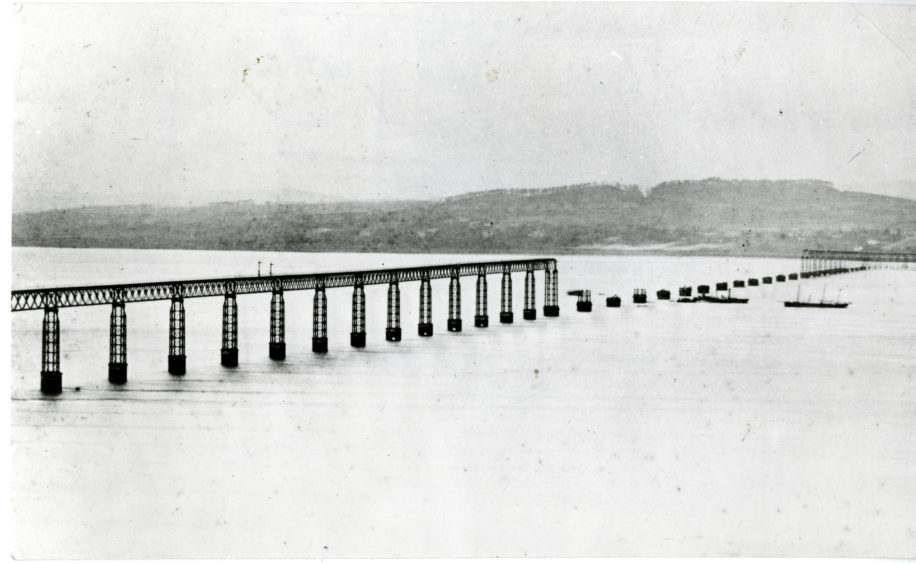

Having taken six years to build and being the longest bridge in the world at the time, it represented the cutting edge of 19th century technology with everyone from the Emperor of Brazil, Prince Leopold of the Belgians and Queen Victoria herself coming to pay homage to this marvel of Victorian engineering.

But on the night of December 28, 1879, the unthinkable happened.

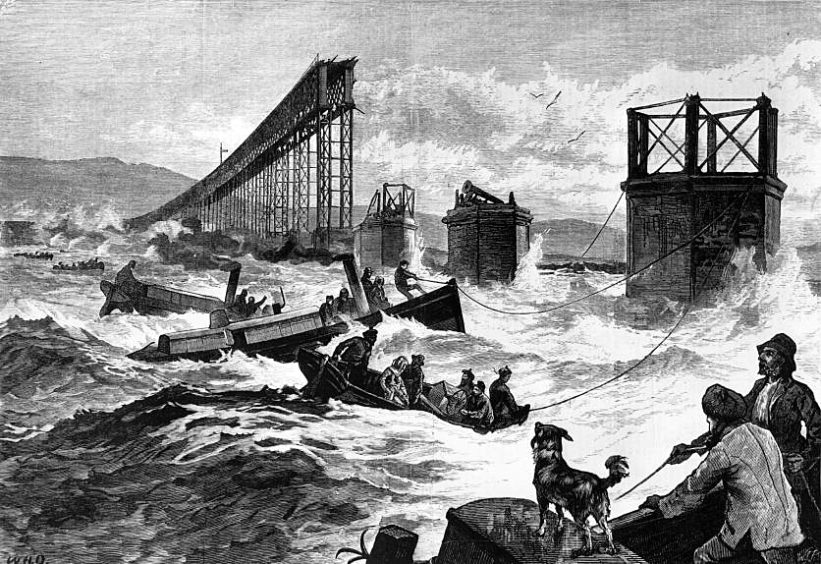

Battered by a ferocious storm, the 13 ‘high girders’ of the rail bridge over the Tay estuary collapsed into the river below, carrying with them a train and all its passengers and crew. There were no survivors.

There has been much debate over the years on what caused the fall of the Tay Bridge and who was really to blame.

The Board of Inquiry concluded that a combination of design failures, construction and maintenance were at fault, with renowned engineer Sir Thomas Bouch officially blamed.

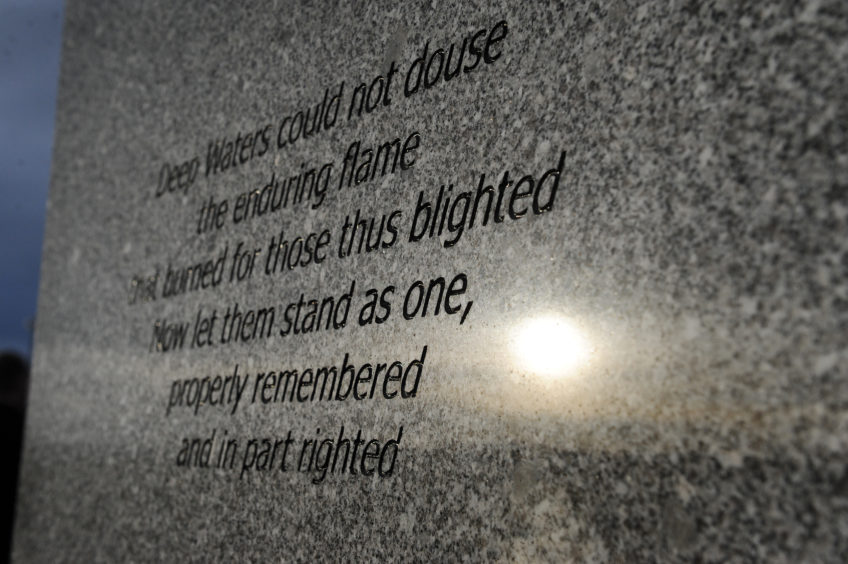

But as thoughts again turn to the disaster on this, its 140th anniversary, former Tay Rail Bridge Disaster Memorial Trust secretary Ian Nimmo-White, who helped establish memorials at the Wormit and Dundee ends of the bridge in 2013, said that even now, debate continues about the cause and how many lives were lost.

“It’s been claimed over the years that 75 people died in the disaster,” said the 71-year-old retired Fife Council youth and community officer who now lives in Forfar.

“But the death toll has been much exaggerated over the last 140 years and particularly over the last 70 years since the last surviving witnesses and relatives began to pass away.

“This is because most people want to believe in the fantasy of a figure higher than the official one of 59. There was never any evidence of a 60th victim let alone a 75th. That’s why we put 59 names on the memorial. We couldn’t do anything else because there were only 59 death certificates.”

With 13 of the 59 bodies unrecovered, it was suggested by some authors that further bodies could have been lying in the silt of the riverbed. But Mr Nimmo-White said this would have been “scientifically impossible”.

“When victims drowned, some would have been pulled seaward by the tide, and others would have sunk to the bottom,” he said. “But after a week, the latter would have filled up with gas and floated back to the surface.

“Secondly, and crucially, Dundee was the last stop for the disaster train that night. Also crucially, 57 out of the 59 victims were expected to be coming off the train at Dundee that night.

“This was the 28th December. They were either returning to work and/or family in the Dundee area after Christmas visits in Fife/Edinburgh/further south, or returning from a day trip over this exciting new bridge, or visiting relatives in Dundee for Hogmanay. Whether bodies were recovered or unrecovered, they were all accounted for.”

Referring to research by local expert Professor David Swinfen – the former chairman of the Tay Rail Bridge Disaster Memorial Trust – Mr Nimmo-White said that while a combination of factors caused the disaster, the main issue was the “poor build” of the bridge.

“All sorts of short cuts were taken to save money,” he said. “Worst of all was, when, during the build about one year from completion, two piers of the high girders fell into the water.

“When they were recovered, one was okay, the other bent. They straightened out the faulty one and put both of them back up – a huge error as it turned out, for sadly, metal fatigue was a phenomenon not as yet confronted by British scientists.

“It wasn’t long before the faulty one became bent again and in turn kinked a rail above on the track.”

Mr Nimmo-White said it was his belief that the lightest carriage on the train, used for second-class passengers, lifted from the kinked rail under pressure of the storm and smashed into the angle iron between two girders.

“This severed the carriage and the mail van behind it from the four carriages and engine in front of it, and the weaknesses in the bridge were exposed, resulting in a domino tumbling of the high girders, taking the train with them,” he explained.

There’s no doubt that the Tay Bridge Disaster still shocks people. To this day, many rail passengers crossing the replacement bridge, which opened in 1887, gaze down at the ‘stumps’ of the old bridge still protruding from the Tay and reflect on the unimaginable events of 1879.

One of the places where the human tragedy really hits home is in Dundee’s McManus Galleries where a display of artefacts includes a first class carriage window from the ill-fated train and a girder from the original bridge itself.

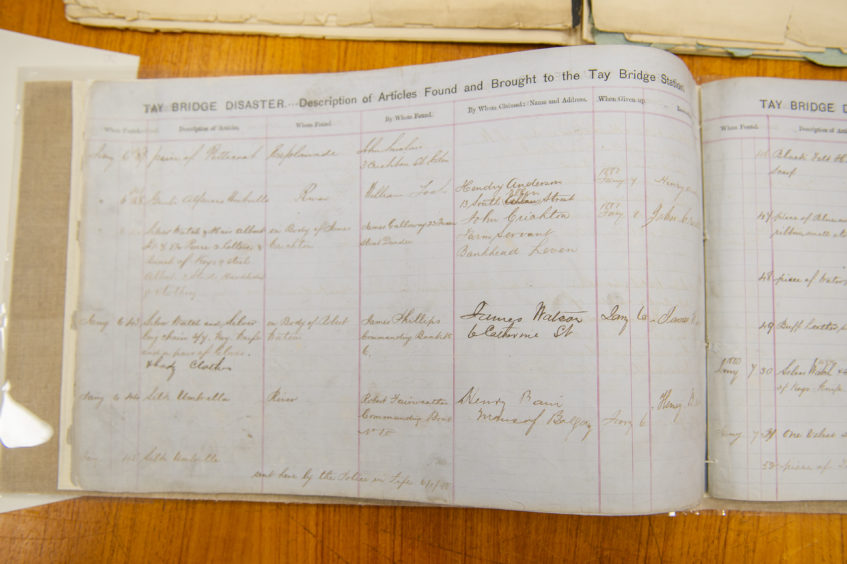

Other items in storage at nearby Barrack Street include a passenger’s toy kettle, a pair of women’s gloves, poignant never to be delivered letters and a pocket watch from train fireman John Marshall which stopped just after the disaster.

“When we speak about it in the museum, I like to speak about it as ordinary people going on a journey,” said Julie McCombie, social history curator at the McManus.

“They didn’t know that this was going to become a really important part of history and that lessons were going to be learned from it in terms of bridge design and construction.

“It was just after Christmas. We have a toy kettle. It could have been a gift for somebody. It could have been a grandma bringing it for a kid, or a child on the train going to visit someone.

“People were probably getting ready to get off when it happened. The recent Rep play expressed the human element of ordinary people going about ordinary life, and that’s something that we really focus on here.”

The McManus collection includes a launch-day programme celebrating how the bridge would revolutionise travel between Dundee and London as well as “souvenir” cups and saucers that reflected the excitement of Dundee being at the forefront of this technological revolution.

Julie said many of the “more human elements” were washed up on Broughty Ferry beach.

As was customary at the time, collected items would be scavenged and made into souvenirs. For example, the museum collection includes a tiny easel carved from railway carriage wood and designed to “remember the dead”.

While much had been written about the causes of the disaster and the large loss of life, it’s also sad, she said, that bridge designer Thomas Bouche “never forgave himself” and died shortly after.

“For me the most poignant thing in the collection is probably the girder – and the window as well,” she added.

“You can imagine people looking out of it just seconds before disaster struck. It could have been anybody.

“These weren’t special people. These were people on an ordinary journey and it just so happened they were on that train. It is very very sad. We’ll never quite know who was on that train. But when I talk about it I always bring it back to the people.”

Growing up in Edinburgh, Dr Erin Farley would often visit Dundee as a youngster to see relatives and, like many children, was fascinated by the “stumps” of the old bridge below. She remembers her father reciting Tay Bridge related poetry as they crossed.

To this day, however, the library and information officer at the Local History Centre in Dundee’s Central Library said the disaster continues to generate an “emotional response” from many people.

She is regularly contacted by folk wanting to find out about ancestors who died in the disaster.

Whilst the library archives include contemporary newspaper accounts and drawings from Dundee magazines and the Illustrated London News at a time when photographs were scarce, she said it’s the number of poems written in the immediate aftermath that are particularly striking.

“People were writing poems on the night of the disaster itself,” she said.

“It’s quite striking how people immediately responded to that. It’s interesting now because everyone knows the McGonagall poem. But his poem sits quite typically with what people were doing at the time.”

Dr Farley said the disaster impacted on the psyche of the city and the wider area for a long time and influenced how people viewed the river.

The fact that many people still quietly reflect on the disaster when they cross the Tay after all these years underlines the fascination folk – particularly locally – still have.

“Sometimes I think we forget how unique the Tay Bridge was at the time it was built,” she added.

“It was the longest bridge anywhere in the world and it had become this total symbol of technical progress that Dundee was really proud of and it represented Dundee being a modern industrial city.

“As well as having lost a lot of people from the city in that immediate disaster thing, it also maybe felt like a blow to progress itself as well.

“There’s definitely a lot of symbolic things that have made it a really iconic part of Dundee’s history. But it’s also a disaster which for anyone travelling by train to this day, doesn’t even bear thinking about.”