Amid claims that Britain has whitewashed its history of slavery and imperialism for too long, is it time for Scotland’s ‘racist’ statues to be torn down or should they remain so that we can learn from history? Michael Alexander reports.

As the post-George Floyd death anti-racism movement gathers pace, cities up and down Britain – including Dundee – have been forced to shine a light on the darker sides of their history.

The toppling of the Edward Colston ‘slave trader’ statue in Bristol last weekend epitomised the urgency of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement while a “topple the racists” website has now published a list of at least 78 statues “celebrating slavery and racism” it wants torn down.

In Tayside, the list includes the statue of Blairgowrie-born politician and reformer George Kinloch, known as the ‘Radical Laird’, who inherited a slave plantation in Jamaica, and on Dunmore Hill, overlooking Comrie, the Melville Monument commemorates Henry Dundas – an 18th century politician who obstructed the abolition of the slave trade and advanced the exploitation of the Empire.

Other Scottish statues featured on the hit list include the Henry Dundas monument in Edinburgh; 1st Earl Roberts statue, Glasgow; James George Smith Neill Statue, Ayr; “Jim Crow” Rock, Argyll; John Moore statue, Glasgow; Lord Clyde statue, Glasgow; Lord Robert monument, Glasgow; Robert Peel statue, Glasgow; The Kitchener Memorial, Glasgow and the Thomas Carlyle statue, Glasgow.

But with statues of “heroic” Second World War Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Queen Victoria defaced in England amid claims they were imperialistically “racist”, and a statue of Scouts founder Robert Baden-Powell under threat of removal amid fear of attack in Poole, Dorset, where is the line between offence and political correctness gone too far?

Former Dundee University lecturer Dr Peggy Brunache, of Perth, is a Glasgow University lecturer on the history of slavery.

The Haitian-American agrees with the removal of “racist” statues. However, she says this should be part of an “assertive programme” to not erase the characters from history altogether. Instead, their slaving past and thus their economic, political and social influences on society must be discussed together.

“The de-plinthing of statues appears to be to many unaware observers, at best, a type of hollow performative allyship, or at worse, a rushed anarchy-fuelled misdirection of action,” she told The Courier.

“What seems to be dismissed are the efforts by local social justice activists, often patiently applied for decades, following the official channels of protocol to address city councils for these statues’ removal.

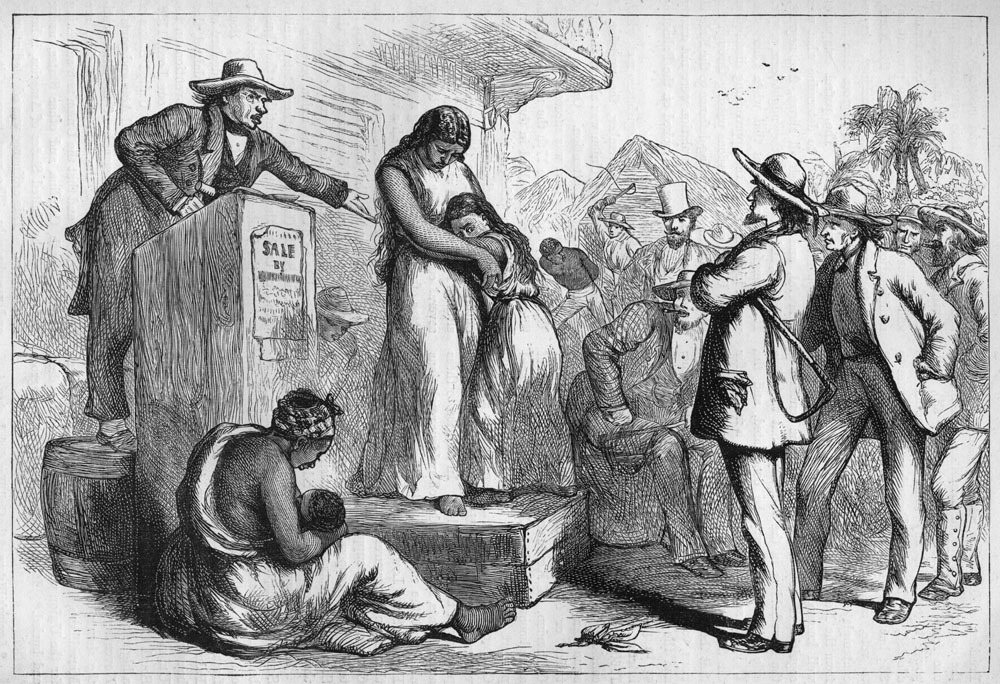

“It seems the lack of attention to address the problematic memorialisation of certain men of society, whose wealth was directly acquired through the forced physical exploitation and racialised violence of enslaved Africans, aligns with some of the contemporary legacy of slavery and anti-Blackness racism that still has America in its grips.”

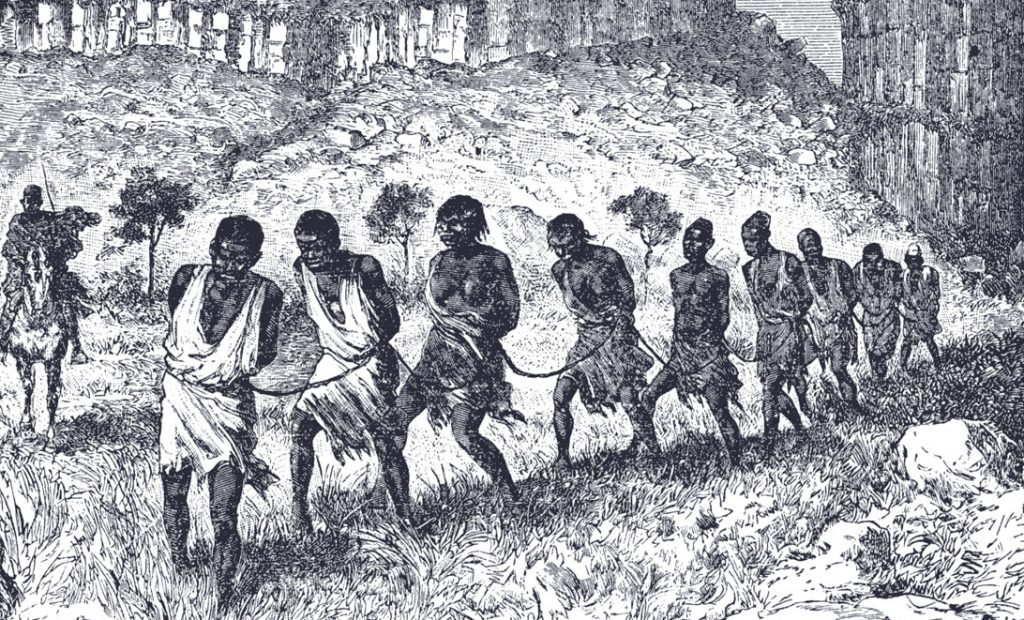

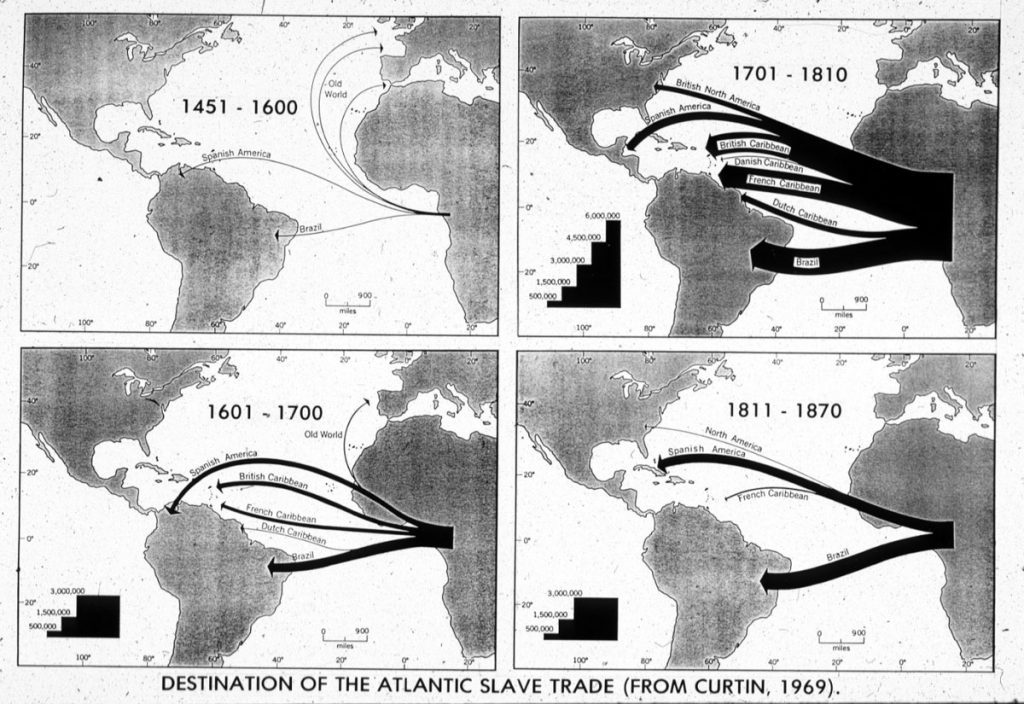

Dr Brunache highlighted how so much of Britain’s wealth that launched her as an industrial behemoth was directly made possible because of the forced importation and violently forced labour of hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans and their descendants.

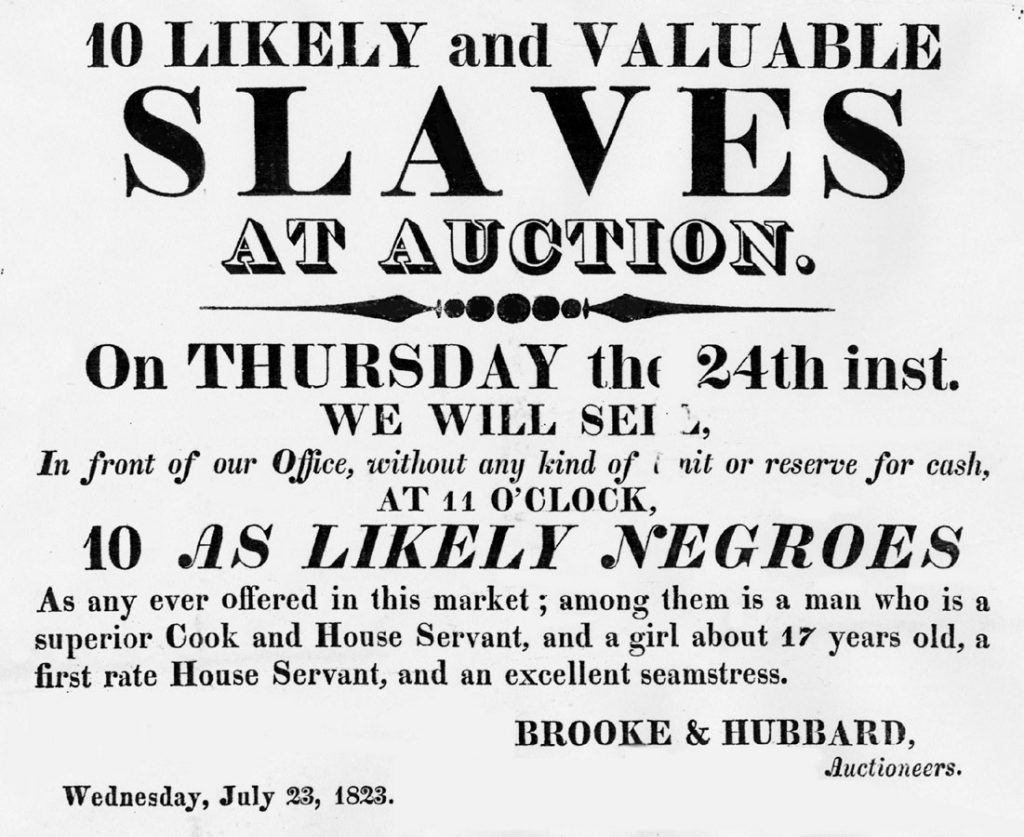

Tayside and Fife was not immune from these links with the University College London Legacies of British Slave-ownership database listing at least 17 Perthshire and 21 Fife former slaveholders and dependants filing compensation claims for the loss of revenue when slavery ended in the then British Caribbean islands.

Dundee’s linen industry – crucial to the growth of the domestic economy – was also heavily connected with the slave trade, as were numerous Montrose-based ships.

Before the domination of jute, most of the linens produced in Dundee textile factories during the 18th into the early 19th century , were exported to the United States and the Caribbean, including a significant amount of fabrics (‘slave coth’) to be worn by enslaved blacks.

Sugarhouses, factories to further process sugar cones imported from British sugar plantations, were also present in Dundee and Edinburgh.

But Glasgow-raised author Maggie Craig, 68, of Huntly, who recently wrote about former Dundee MP George Kinloch in her book One Week in April: The Scottish Radical Rising of 1820, told The Courier it would be a “tragedy” to take down his statue in Dundee’s Albert Square – and she questioned the extent of his slave trade involvement.

At a time when the conditions for working class Dundonians including weavers were desperately poor with no democratic rights, Kinloch – a local laird and landowner who was instrumental in the development of Dundee harbour – fought with thousands of workers for peaceful parliamentary reform.

He later became MP for Dundee in the first parliament elected after the Great Reform Act.

Maggie said: “I’d say the statue/s should stay, with plaques explaining the context – if there is evidence for this.

“However, I’m a wee bit worried that people are getting their history from Wikipedia.

“On Wikipedia it says that he inherited a plantation and slaves in Jamaica but sold it some years later.

“But on the UCL slave owners’ database this is not mentioned, only that he was a ‘slave owner in Jamaica’ which is hardly accurate. I’m fairly sure he never went there.”

Maggie said that In The Radical Laird by Charles Tennant his uncle John Kinloch’s Jamaican estate is mentioned as having been left to George’s father, George Oliphant Kinloch. She wonders if people are getting the two Georges “mixed up”?

She added: “On reflection, I think it would be a tragedy if the statue were removed.

“The radical laird was a highly important figure in the reform movement, which led eventually to democracy, universal suffrage and a vast improvement in living and working conditions. Any plaque would have to mention that too.

“I can well understand the howls of anguish and anger following on from George Floyd’s murder but I’m getting really angry now about targeting people whose statues don’t deserve to suffer this backlash.

“As a descendant of Lanarkshire miners, I’d also say that Scottish miners were serfs/indentured servants until 1799. To me, it’s as much about class as colour.”

Dundee University human geography lecturer Dr Susan Mains taught for nearly 10 years at the University of the West Indies-Mona in Kingston, Jamaica – an English colony from 1655 and a British colony from 1707 to 1962.

It was a “very special experience” that inspired her to be more reflective and critical of her own assumptions about place, about Scottish identities and the role of Scotland during colonialism.

While there, she became increasingly interested in understanding the impacts of colonialism, alongside the contradictions of living in a place that is promoted as a popular tourist destination while simultaneously being a country that has had significant levels of emigration.

She told The Courier that public statues that commemorate historical figures who were actively involved in the slave trade are “problematic”.

“We have to ask ourselves: what is the role of a statue?” she said.

“If it is to memorialise, celebrate and hold aloft, then what is it we are celebrating?

“Do we value the permanence of statues, their aesthetics and their familiarity over the people who suffered as a direct (and indirect) consequence of the activities they supported?

“How can we reflect and engage with the complexities of history more critically? What new, more inclusive forms of recognition can we have in our public spaces?

“Statues, and their meanings, are going to vary a lot and the conversations we have about this will be varied too.

But, most importantly, these discussions have to be about more than statues.

“Any changes that are made should be working towards reducing inequalities, improving social justice and increasing the diversity of voices that are heard and represented.”

Dr Michael Morris, senior lecturer in English and history within the School of humanities at Dundee University, did his PhD on a cultural history of Scottish connections with the Caribbean between 1740-1838.

He’s been researching how Caribbean slavery helped shape Scotland’s economic, social and cultural development and says there’s no doubt the findings are “troubling”.

Regarding Dundee and its statues, he said it would be a “good idea” to conduct a full study of slavery connections in and around Dundee to get a detailed picture.

“That way we can best decide what to do with street names, and sculpture and portraits of the likes of George Kinloch,” he said.

However, Leven-based author and historian Lenny Low, who has campaigned for a memorial to those wrongly persecuted of being “witches” in 17th century Fife, believes it’s “absolute nonsense” to remove statues.

He said: “I’m from a village in Fife called Largo where Largo Castle – the home of the first Admiral of Scotland Sir Andrew Wood – was built by English prisoners as slave labour in 1488 onwards. My thoughts to this are exactly what they should be – a piece of history.

“There are no prominent statues to the persecutors of witchcraft except any statue to Mary Queen of Scots who in 1563 endorsed the Witchcraft act of Scotland.

“Again the thought of removing her statues is nothing but vandalism.

“History is here for us to remember our faults and learn by them. We are not here to erase the nasty history and leave the good stuff to remember. The height of absolute nonsense is to remove statues. It’s time we took a stand against such folly.”

Looking at the wider prevalence of statues in Scotland, it might be possible to find a positive or negative narrative for most historic figures.

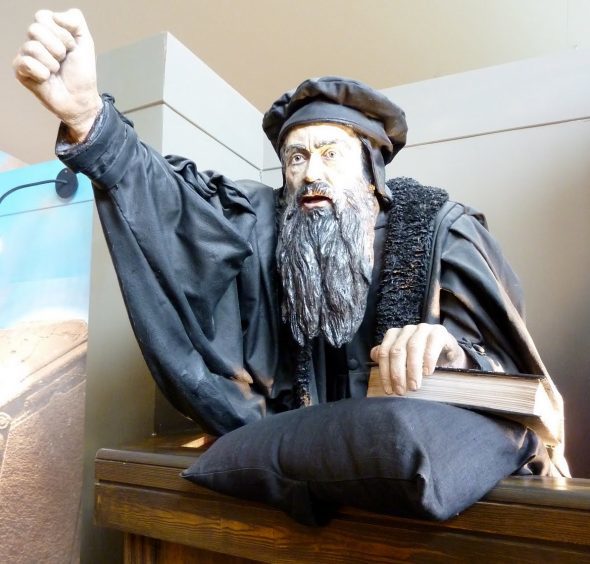

For example, was 16th century Protestant preacher John Knox, whose statue can be found in Edinburgh, a welcome religious reformer or the St Andrews Cathedral wrecker who whipped up persecution of Catholics?

Was Robert Burns – immortalised in statues like the one in Dundee’s Albert Square – a national hero or a racist, sexist drunk?

Should the likes of Fort George and Fort William have their names changed to severe their links with the brutal violent suppression of Highlanders, and why does a memorial still stand near Golspie to George Granville Leveson-Gower, the first Duke of Sutherland – the man blamed for some of the most notorious of the 19th century Highland Clearances?

It’s a point picked up by Dundee historian Norman Watson who said the nationwide re-examination of memorials in the light of the appalling death of George Floyd has placed many historians in a difficult position.

“Figures linked to the slave trade should not be celebrated in any shape or form,” he said.

“Though, as a historian, I would rather inappropriate statues and monuments be preserved by museums and their original purpose explained and put into historical context.

“But what appears tainted and representative of oppression to one might draw unqualified support from another, who remembers only the positives of a person’s life.

“For instance, would we have a statue of Oliver Cromwell in Dundee, when in 1651 his New Model Army butchered about 1500 citizens? Of course not.

Yet, today Cromwell’s statue is outside the Houses of Parliament and, in 2002, he was voted in the top 10 ‘Greatest Britons’ of all time.

“A statue of Winston Churchill here would be as welcome for many as a swim through vomit. But he received the Freedom of Perth. He, too, stands on Parliament Square, on a spot where he modestly pointed out, ‘That is where my statue will go’.”

Dundee, said Dr Watson, lagged behind most Scottish cities by having, until recent times, only four Victorian statues grouped around the McManus Galleries in Albert Square.

“The statue of the city’s first MP, George Kinloch, would have to be toppled as he inherited a slave plantation. Queen Victoria would have to go as she ruled over an expanding empire (maybe a name change for the V&A, too?).

“One of the only statues of Robert Burns in Scotland would have to be removed because of his misogynist leanings.

“James Carmichael, opposite the old Chamber of Commerce, worked on innovations that produced the cheap linen that clothed thousands of slaves in the New World.

“So that’s four out of four for the wrecking ball.

“Where do we stop? Do we pull down Desperate Dan’s chest-bursting statue at ‘Samuel’s Corner’ – the most photographed of Dundee’s 120 pieces of public art – because he shot down the Luftwaffe with a peashooter during the war? Does Gnasher’s comic behaviour encourage attacks on postmen?

“Do we weed out all those stained-glass windows dedicated to and paid for by wealthy slave drivers at the end of their lives in the hope of closing the gap on their Maker?

“What of Baxter Park with Sir John Steell’s white marble statue of Sir David Baxter – a linen lord who sent shipments of ‘negro clothing’ to Savannah and New Orleans?

“Lochee Park, the gift of the Cox brothers in 1891, has always been on a sticky wicket. The textile millionaire brothers bequeathed its 25 acres principally for the ‘working people of Lochee.’

The citizens repaid the compliment and exercised ownership by cutting down its trees for fuel during a factory lock-out!

“Dawson Park, on Arbroath Road, was the gift in 1940 of William Dawson, a director of George Morton, wine and spirits merchants. How many lives have been ruined by alcohol?

“Soon, all we’d be left with are those wonderful penguins!”

Few mortals have unblemished pasts, he said, but ultimately it is up to local authorities to consider removing tributes to controversial figures and the ‘appropriateness’ of other monuments and landmarks.

“Improved accuracy to our history, including the impact of wars, slavery and oppression, would be welcome, as long as it’s re-examined and re-analysed – and not erased,” he added.