The SS Californian made headlines in Dundee before she became embroiled in controversy when the Titanic struck an iceberg and sunk.

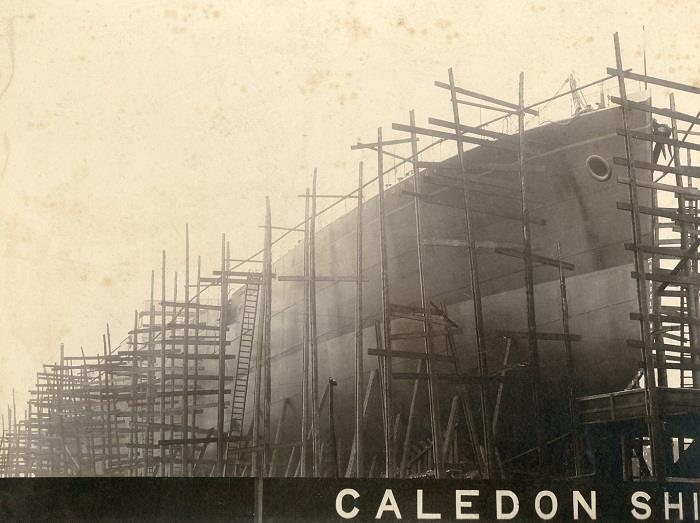

The Californian was a Leyland Line steamship and construction began on the north bank of the Tay 120 years ago in November 1900 which generated massive interest and extraordinary scenes in Dundee as it progressed over the course of a year.

Following its tricky beginnings being built at Caledon Shipyard, life got no better for the ship when she finally left her city of birth and now she will forever be associated with the disastrous maiden journey of the White Star Line’s gigantic vessel.

The ship was eventually launched from Caledon Shipyard on Tuesday November 26 1901 and moved to Victoria Dock next to a 90-ton crane.

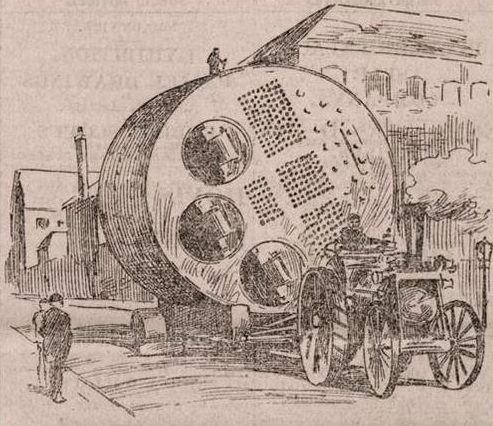

Its engines and boilers were being made in the Lilybank Foundry and all that was needed was to transport them through the town to the docks.

Californian’s engine weighing 51 tons was moved to the docks but caused damage to tram lines and a large number of stones were crushed.

Horrified

The local magistrates were horrified at the prospect of more damage to the streets from the two boilers which each weighed 85 tons and issued a ban.

The starboard boiler was being taken down to the docks at night on a special 20-ton bogie when it was stopped on Kemback Road by a police officer who handed the party an order from the magistrates prohibiting locomotive traffic on that street.

The huge boiler could not be taken back because of the steep incline and it was left there until the local magistrates discussed the matter with the manager of Caledon Shipyard and agreed to suspend the ban until December 6.

Work resumed on Saturday November 30 and thousands turned out in the early hours of the morning to watch.

The starboard boiler was pulled out of Kemback Street by two bogies before it got stuck fast on Arbroath Road.

To make matters worse, the weight of the engines burst a five-inch water main and the water flooded the street.

The burst had the effect of softening the ground underneath and gradually one of the rear wheels of the bogey sunk four inches.

To make progress, heavy logs were placed at the rear of the engines, and strong chisels were driven into the street to keep the logs in position.

The efforts of the men to move the bogie were successful after about an hour and a half and a new start was made and progress was rapid.

The boiler sank and lay stranded at the top of Reform Street after leaving a trail of ripped up and scratched bricks and pavement in its wake.

Barricade

Police put up a barricade to keep people back and stayed on the ground all day before 4,000 to 5,000 people turned up to watch the resumption of the work at midnight with some perched on balconies and lorries to get a better view.

Plates were put in front of the bogey wheels before a series of hawsers and chains were attached to the engines.

There was a deafening cheer as the boiler passed down Reform Street with the spectators following and the procession continued its way down Commercial Street and along Dock Street to the harbour entrance before it was placed alongside the Californian.

The removal of the second boiler was a greater success and by the end of December 2 both boilers were lifted and installed into the hull of the Californian although the damage to the road left the Caledon Shipyard with a £829 bill for repairs.

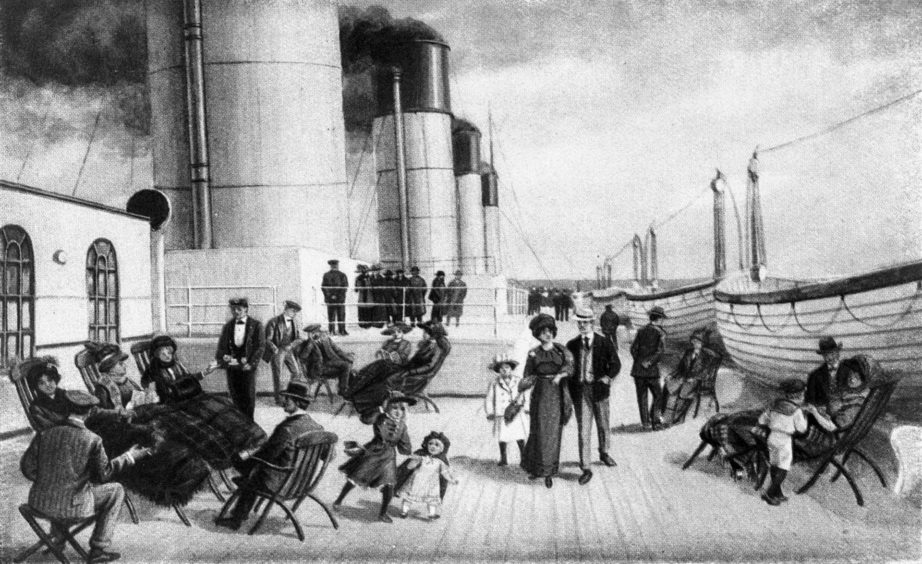

After the boilers, outfitting continued on cabins and the decks and Californian was moved into the East Graving Dry Dock to have her masts fitted.

Later when a crane was being used to rig a spar on one of the Californian’s four masts, the spar became tangled in nearby telephone wires and severed them.

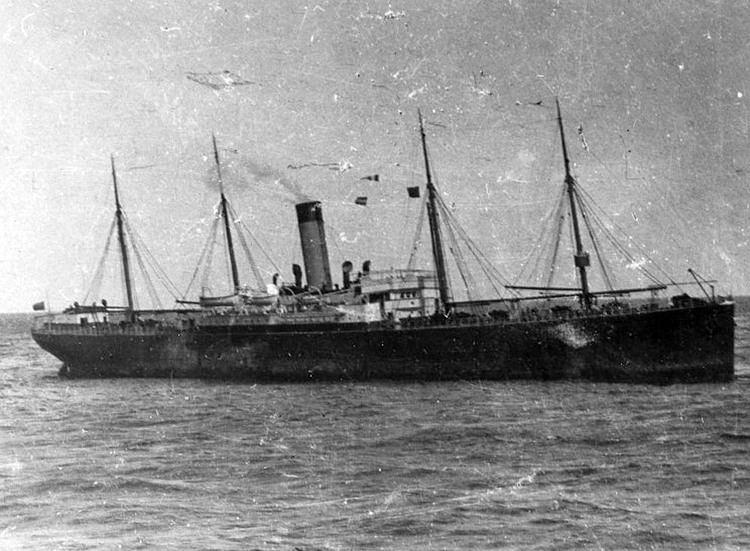

She completed her sea trials in the River Tay on January 23 before she made her maiden voyage to New Orleans.

White Star Line

The Californian was initially built for cotton transportation but it was then taken over by White Star Line, the company which also owned Titanic, and was extended to include passengers.

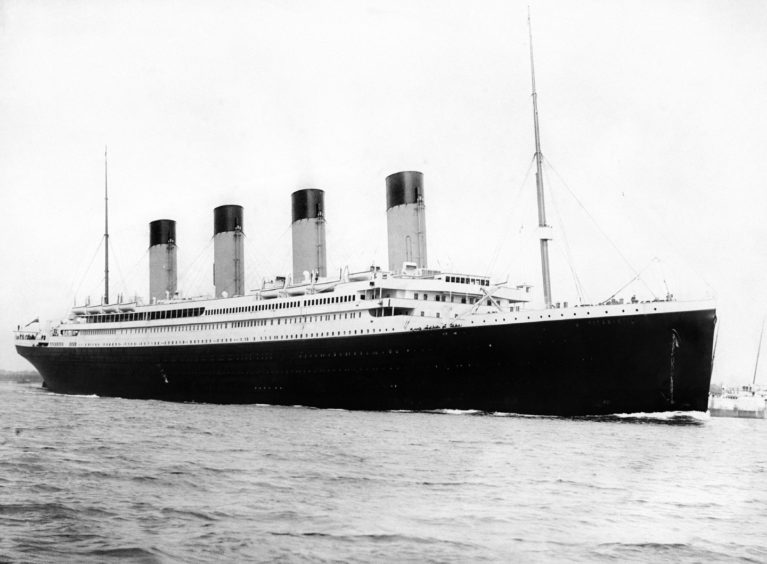

The Californian was on its way to Boston on the fateful night of April 14 1912 and nearest to the Titanic when it hit the iceberg.

Stopped in ice, over the course of the night the crew on watch saw a ship’s mast lights and rockets exploding overhead and woke Captain Stanley Lord to tell him what was going on.

However, the Californian stayed where she was all night.

It was left to another ship, the Carpathia, to come to the Titanic’s aid, manoeuvring around icebergs to get to the scene.

But by the time the Carpathia had arrived, the Titanic had sunk.

Just over 700 people lived to tell the tale, with the Carpathia taking them to New York.

The captain of Carpathia said it was an ice field, with 20 large icebergs of up to 200 feet high and many smaller ones, along with ice floes.

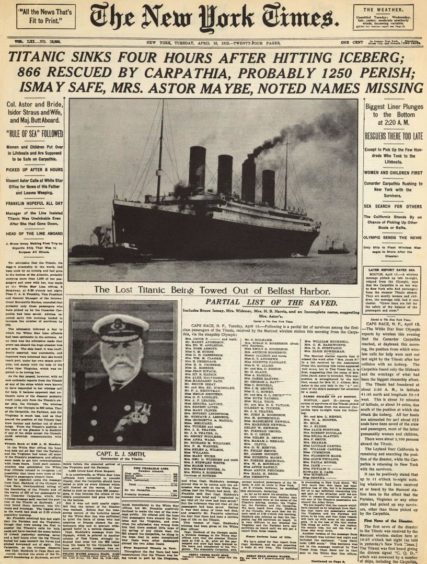

More than 1,500 passengers and crew died in the disaster on Titanic’s maiden voyage from Southampton to New York.

Captain Lord was summoned to appear as a witness at both the US and British inquiries into the loss of the Titanic.

He maintained that he would have been unable to reach the ship in time.

Both inquiries concluded that the Californian could have forced its way through the ice to save lives.

Criticism

Despite the criticism, no formal charges were ever brought against him and he spent the rest of his life trying to clear his name.

On November 9 1915, while travelling from Salonica to Marseilles, she was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-34.

But it said he could have done little anyway to help the drowning passengers.

One of Dundee’s most famous whalers, the Scotia, part of the Kinnes Shipping fleet, played an important role in trying to prevent another such tragedy.

She inaugurated the North Atlantic Ice Patrol in 1913, sailing on government charter to act as an ice scout.

News of the sinking of the largest ship afloat at the time caused panic around the world

Now one of the most documented disasters in world history, details of what unfolded on that fateful night took time to filter through.

Indeed, it was more than 24 hours after the collision before the grim reality of what happened was captured in print.

News had also filtered through that pioneering English newspaper editor, William Thomas Stead, was among those missing.

This turned out to be true, and he is regarded as having been one of the most famous people to have lost their life in the disaster.

Dundee Law

Always keen for a Dundee angle, the Evening Telegraph attempted to describe the scale of the ship by writing: “If the Titanic were placed on end, she would rise fully 400 feet above the Law”.

A reporter also spoke to a Dundee whaler, who told of an incident in which he and his crew narrowly avoided being crushed by two icebergs.

“It was an unforgettable incident, and I fully realise what the Titanic must have experienced,” he said.

Some 16 years after the disaster, it emerged that a Dundee woman was set to find a rare piece of fortune amid the tragedy.

Mrs Burns, of Main Street, was set to inherit around £250,000 from a distant relative who died aboard the Titanic.

In a bizarre twist, the immediate heir to the money also perished in a ship disaster not far from the resting ground of the Titanic.

In today’s money, the amount of cash Mrs Burns was set to inherit equates to more than £25 million.

Broughty Ferry man’s key could have saved the Titanic from sinking

A key which could have potentially saved the Titanic from sinking was carried by a second officer from Broughty Ferry.

The small iron key, thought to have secured the binoculars for the Titanic’s crow’s nest, had been accidentally taken off the ship before it sailed.

In an inquiry after the Titanic sank, one of the lookouts said the binoculars could have prevented it from hitting a giant iceberg.

Disappointment

The key was carried by David Blair who was replaced at the last minute by another second officer and failed to pass it over.

He certainly wanted to be on board — Blair wrote a postcard home, saying: “This is a magnificent ship, and I feel very disappointed I am not to make her first voyage.”

Others have suggested that Blair left the binoculars in his cabin, while a third theory claimed he had taken the binoculars, not just the keys, away with him.

Blair was first officer on the SS Majestic in 1913 when a coaler jumped overboard.

While a lifeboat was organised, Blair jumped into the ocean waters and swam toward the man.

Though the boat reached the man first, Blair was commended for his action in The New York Times and received a King’s Gallantry Medal.

Among other medals he received were a British Empire Medal, a French Cross of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, a Royal Naval Reserve Decoration, and an OBE.

Blair was a friend of Charles Lightoller, who took his place as second officer aboard Titanic, and remained friends in their later years.