Michael Alexander speaks to Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate Stella Rooney and former Dundee Timex worker and trade union activist Charlie Malone about an art project exploring political education on the picket line of the 1993 Timex dispute.

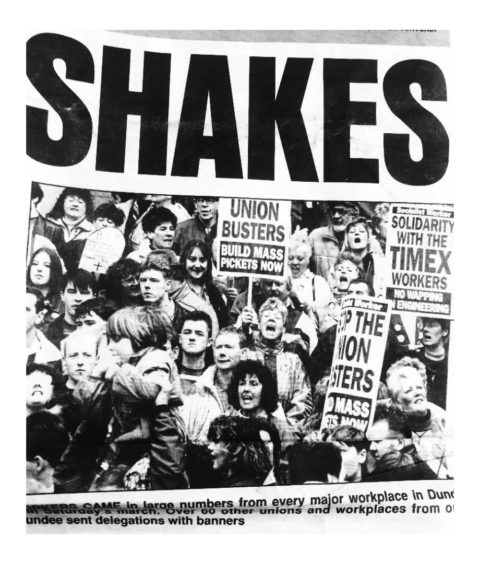

It was the most significant industrial struggle in the history of Dundee, involving mass picketing and demonstrations, solidarity walkouts and strike action as well as clashes with the police.

The 1993 Timex dispute, which media reports at the time cited for its level of picket-line violence, resulted in the closure of the Timex plant in the city after 47 years.

Twenty-eight years later, and for many in Dundee, the scars and frustrations of that dispute, which followed previous action, run deep.

But for one Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate who wasn’t even born when the dispute happened, the struggles faced by the workers have important lessons for today in a world of low pay for many young people and zero hour contracts.

On Thursday March 25, art and philosophy graduate Stella Rooney, 22, from Glasgow, will facilitate an online in-conversation event being hosted by the university’s Cooper Gallery which focuses on Dundee’s Timex factory and strike.

Retired teacher and Timex Support Group activist Mary McGregor and former Timex worker and trade union activist Charlie Malone, who was chair of the strike committee during the 1993 strike, will discuss their experiences and explore education on the picket line.

Introducing the event is Stella’s own film, shot at the location of the Camperdown Timex factory, that looks at the legacy of the factories and the effects of deindustrialisation on the city.

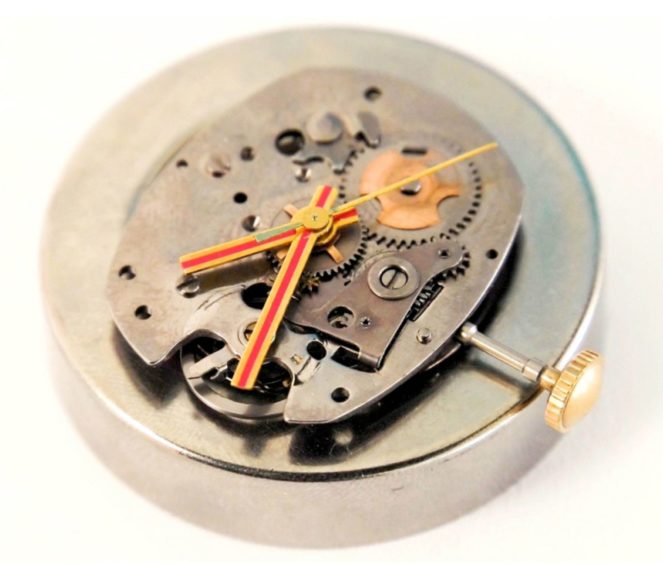

The event is part of a wider Cooper Gallery project, The Ignorant Art School – the first chapter of which has been organised by internationally celebrated artist Ruth Ewan and is built around the capitalist construction of time.

Degree show legacy

As a 2020 graduate from DJCAD’s art and philosophy programme, Stella’s final year project focused on the legacy of Timex factories and the effects of deindustrialisation on the city of Dundee.

Stella is also an activist campaigning against precarious work and was part of organising a 14-day occupation of the university Principal’s office while a student.

However, because of lockdown last year, she never got to properly finish her Timex project.

She is therefore delighted to be able to showcase some of her material as part of this new venture now.

“I spent my last year at DJCAD working on a project about Timex,” explains Stella in an interview with The Courier.

“I did a lot of research on it. I looked at archives. I worked with the Timex history group who meet in Douglas.

“They’ve been archiving different bits of the factory including the strike but not just limited to that. I interviewed people who were former workers or involved in the strike.

“It’s unfortunate that because of the lockdown I never got to properly finish that project but I did produce a short film with three workers who worked in Timex – they left the factory in the ‘80s so they had a different experience to those involved in the final dispute.

“But even though I had no connection to Timex, I thought it was really interesting.

“For me as a young person, the world of work that we’ve inherited is very different from a time where people had jobs in factories and there were a lot of jobs like that going round.

“Everyone I spoke to seemed to have a very bitter ending to the time in Dundee.

“But in its heyday people really enjoyed Timex. Loads of people worked there.”

Interest in working class history

Born and bred in Glasgow, the former Hillhead High School pupil realised in fifth year at school she wanted to study art and fell in love with Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art on a trip to the city.

Although she had no connection with Dundee, its working class character reminded her of Glasgow and she instantly felt at home.

Having stood up for workers’ rights in the past, Stella has a long standing interest in working class history – not just because it’s interesting in itself, but also because she thinks there’s a lot that can be learned today.

“Before I went to uni, I was involved in campaigning against low pay for young people and zero hour contracts,” she says.

“I think that by looking at the way work has changed, and the way working class peoples’ lives have changed, we can definitely learn a lot about where we need to go now and how we can improve things.”

Stella has used some of her degree show footage in the new film, but she’s also used a lot of new footage including archive film and photos.

“I’ve also worked with Mary McGregor to record a voiceover that goes through it,” she says.

“Part of that is an extract from a poem by Mary Brooksbank who was a very famous trade union activist in the jute mills and she was a poet as well in Dundee.

“I was kind of revisiting some of the material that I gathered and researched for my degree show that I never got to kind of put together.

“So it was a really nice opportunity to revisit some of that.”

The Ignorant Art School

Stella is also excited that the event is part of a wider Cooper Gallery project, The Ignorant Art School – the first chapter of which has been organised by internationally celebrated artist Ruth Ewan and is built around the capitalist construction of time.

Questioning what art education is and whom it serves, The Ignorant Art School brings together artists, designers, educators, activists, culture workers, students and other publics, to creatively re-imagine and co-constitute a collaborative and decolonised blueprint for a socially transformative art education that opens towards an emancipated future.

The title of the project is inspired by French thinker Jacques Rancière’s seminal book The Ignorant Schoolmaster, in which Rancière recounts the story of Joseph Jacotot, an exiled French schoolteacher who in 1818 formulated a teaching method that dissolved hierarchies in conventional pedagogical practice.

Repurposing equality as a practice rather than an ideal, The Ignorant Art School examines the histories and future possibilities of art education.

Timex shop steward and political activist Charlie Malone

Abertay University lecturer Charlie Malone was a former shop steward at Timex.

The Labour councillor for the Lochee ward was chair of the strike committee during the 1993 dispute and was a member of the occupation committee and also a shop steward at the 1983 dispute.

Unable to get a job after the 1993 dispute, he studied commerce at university and became a lecturer at Abertay, where, somewhat ironically given the nature of the industrial dispute he was involved with, he’s now head of the division of accounting, business and management.

Charlie first met Stella Rooney through University and College Union (UCU) activism when she was involved in the sit in of the principal’s office at Dundee University a few years ago. He’s also been in touch with her a few times since she joined the Labour Party.

He’s delighted to be part of her project because he thinks it’s important for people to understand the rich deep and diverse history of employee relations in Dundee that stretches back centuries to when Dundee was one of the centres of the Enlightenment.

“What the project is really looking at is political education,” says Charlie, 60, who still feels “frustration and disappointment” when he thinks back to the Timex disputes.

“We’ve got formal political education at university.

“But what about the informal political education that takes place in factories?

“That’s my interest in the project – going back over the events of the dispute, it’s about how we as a community organised ourselves and were very very effective at political communication within the factory.

“Some of the people who taught me – not as a lecturer but some of the shop stewards – that taught me politics in the workplace were as good as the sociologists I’ve seen at any place at any university.

“These people often never got the chance to go to university. But the informal political education existed within the factory for shop stewards, augmented by a deliberate attempt to include other people in the discourse of politics.

“When we had a dispute with the company, we always tried to locate it in a political context. So we were used to transferring that political education to everyone.

“But what I saw was a radical change in 1993, because this was at the end of 10 years of legislation that was trying to make trade union disputes almost a thing of the past.”

Timex was an institution

In Dundee, Timex was no ordinary employer, but rather an institution, an institution that connected with local authorities, employees, trade unions and most importantly, the communities in which it located its business activities.

Everyone in the city knew of someone who worked at Timex.

It produced generations of the most skilled engineers in the country, world leading brands and its employees were some of the most advanced in championing workers’ rights.

Its innovators produced products that would shape the world of computing and spawn the birth of the computer games industry.

If anyone needed reminding of the importance of Timex to the city, it was evident in the dispute of 1993.

People came together in large numbers to defend jobs and ironically, Timex itself.

Strike action against the employer

“I think that people even in Dundee to this day still talk about us taking strike action against the employer,” says Charlie.

“It was actually the employer that locked the employees out. The employer took industrial action against us.

“The dispute finished in the February and it was the employer that took the decision to lock everybody out, sack everybody and replace them with an alternative workforce.

At that point there was only one direction in which this dispute was going, and that was probably failure for the company.”

An outcome of this, Charlie, says, was that political education came as a consequence of the action the company took.

“Workers began to understand things like how many workers you were entitled to have on the picket line, they began to understand the laws and the regulation, and they would quote the regulations,” he says.

“I remember getting the Treaty of Rome quoted at me by one of the people on the picket line saying the company were in breach of it.

“So what I said to Stella was – political action is an outcome of political education.

“If people take part in industrial action that’s got a political dimension to it because they understand the political dimension, that comes through political education.

“That was similar in working class factories up and down the country. Not just Timex. I’m sure the same things went on at NCR and Michelin as well. It’s that sort of organic political education rather than formal political education.”

Social media – a new avenue for political education

The world of work may have changed in recent decades and it continues to do so in a world where many workers continue to fight against low pay and the perils of Zero Hour contracts.

But while the structuralist approach of big factories might be different, Charlie believes the legacy lives on through use of social media and campaigning for ‘single issue’ topics like climate change and the Better than Zero working hours campaign.

“I think social media is providing scope for political education good or bad depending on your political viewpoint whether it’s Extinction Rebellion or the kind of public petitioning of the local authority on things like drugs deaths and male suicide,” he says.

“I think it’s taken a different form, and I think the social media is providing the tool to allow that political education to broaden.

What you don’t have is mass movements across a whole range of spectrums.

“But what you tend to have is movements on individual issues.

“ I think Extinction Rebellion is a fascinating example of how political education can come through what starts off as a very small campaign, but you had the schools on strike for example across the world. That’s political education in action.”

Image from Stela Rooney’s Timex project*A Strike Class: The Clock Stops takes place from 6pm to 7.30pm on Thursday March 25. Free tickets are available on Eventbrite.