Fifty-one years on from the disturbing and tragic shooting at St John’s in Dundee, Michael Mulford – a former Courier reporter and the first journalist to reach the scene on the day – confronts his memories of the day.

Wednesday, November 1 1967 started for me like any other busy weekday as a reporter working for The Courier and Evening Telegraph.

In my worst nightmare I could never have imagined it would end with hearing a dreadful murder being committed.

The events at St John’s School in my home town of Dundee would haunt me for more than 50 years.

The reason I am writing this account now is based on professional advice to confront, at last, the demons which have cunningly remained hidden, but which have kept coming back unannounced for so long.

I was assigned sheriff court duty that day. The court continued briefly into the early afternoon then rose.

I decided to pop my head round the control room door of Fire Brigade headquarters in Bell Street, opposite the courthouse, and ask the usual question: “Anything doing?”

The two firewomen on control duty were busy writing down an urgent message.

I caught the eye of station officer Jock Ross, the watch commander.

Ross, a decorated war veteran and legendary Dundee firefighter, looked at me, blew through his lips, shook his head and indicated a scribbling movement with his hand.

The police had asked for assistance at St John’s. I heard the message being relayed over the telephone to the Northern Fire Station.

I could hardly take in the words – “man with gun holding up a class”.

Within the usual few seconds sub officer Dan Waddell and his crew from White Watch were speeding towards St John’s, barely a minute away.

I was the first reporter to reach the school, which stood just around the corner from my home in Harlow Place.

I knew where the nearest phone box was in Brantwood Avenue and made regular transfer-charge calls to the Meadowside office with updates.

I was standing at the school gate when the air was suddenly rent with a loud “whump” which echoed around the street.

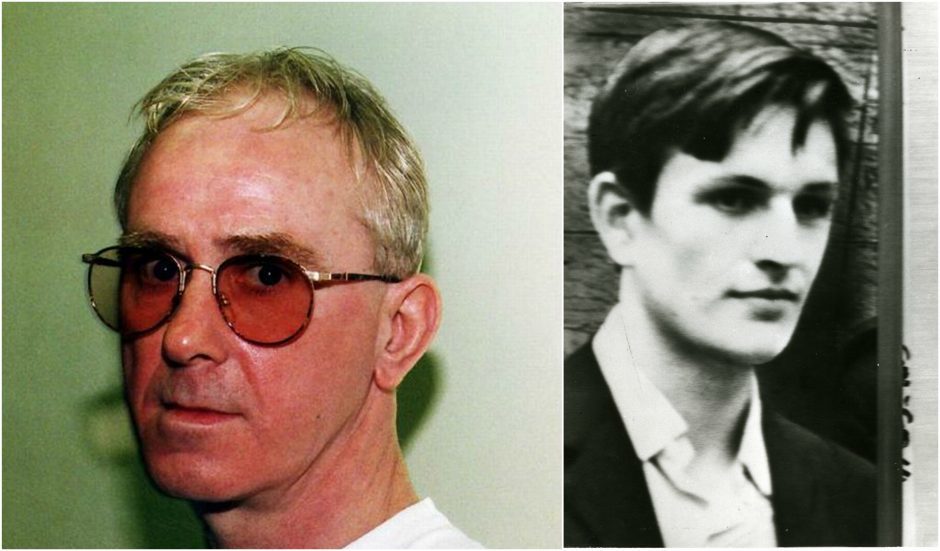

In that dreadful moment Robert Mone, a disgrace to the great name of the Gordon Highlanders, had turned a shotgun on Nanette Hanson, the teacher who had saved the lives of the 11 girls in her care in the needlework class.

He didn’t just murder her in cold blood. He also killed her unborn child.

I recall two firefighters rushing to their fire engine, grabbing first-aid and resuscitation gear and doubling back into the school.

Sadly, all efforts to revive Mrs Hanson were in vain.

Yes, he had a wretched upbringing with his father, Sonny Mone, who later murdered three women, then was himself murdered in Craiginches Prison.

Yes, Robert Mone had been expelled from St John’s. November 1 1967 was payback day – fully justified in his tortured mind.

He was taken from St John’s after the shooting, charged with murder and sex offences, but found insane and unfit to plead.

His destination was as a patient in the State Hospital, Carstairs. It was far from the last I would hear of Robert Mone.

On November 30 1976 two patients escaped from Carstairs leaving a hideous trail of murderous destruction, with another patient, a male nurse and a police officer dead.

I was in my seat in the House of Commons press gallery the next day as parliamentary correspondent.

The Commons listened with palpable shock as Scottish Secretary Bruce Millan read the official statement.

My shorthand outlines crossed the page with relative ease until Mr Millan reached this part: “Since criminal proceedings are pending against the two patients, Mr Robert Mone and Mr Thomas McCulloch, who escaped, it would not be proper for me at this stage to comment on the events, and I shall give only a brief summary of what is so far known to me.”

My pen almost faltered. As I typed up that story I relived St John’s, especially the sound of the fatal shot.

I made the mistake of not talking about that experience then, or for many years afterwards.

In time I was appointed head of communications at the Scottish Prison Service. Mone and McCulloch were then serving long sentences. I am still bound by the Official Secrets Act and simply not allowed to discuss those years.

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of the St John’s atrocity.

I tried then to square up to my demons with a brief, written observation on social media.

I learned at that time that a good friend in the CID, Detective Inspector Jim Melville, had given The Courier an interview revealing that a police marksman had Mone in his sights and could have taken him from the rooftop of shops opposite the school.

Nowadays, they would not hesitate if a gunman was holding hostages and the only thing stopping a slaughter was a temporarily defective firing mechanism on the shotgun.

Mone only beat the hangman’s rope by a few years, and a police bullet in the head by a tactical decision not to approve shooting him.

I fear many people are still living with the aftermath of St John’s – the 11 girls Nan Hanson bravely protected, nurse Marion Young who, with scant regard for her own safety, entered the classroom to join Mrs Hanson, the school staff, the emergency services, Nan’s husband, Guy, and their families.

He and Nan lodged with Margaret Keir – the lady who became my sister-in-law.

The last report I heard of Guy was that he was abroad. I had several friends in the casualty department of Dundee Royal Infirmary and know that many of them were deeply affected.

I knew Marion Young very well – I used to deliver the papers to her family home in Glenesk Avenue which overlooks St John’s.

I went to school with her brother, Jim.

All three of us played football in Balfield Park which is divided by a fence from the school.

Big brother Noel worked for a tabloid and made sure they had the exclusive pictures when Marion was awarded the George Medal.

Nan Hanson was awarded a posthumous Albert Medal (now called The George Cross).

I have not kept cuttings of my report of the shooting, nor The Courier picture showing me at the front gate of the school as the ambulance left. Photographer Ron Gazzard and I travelled to Yorkshire to cover Nan’s funeral, a very sad event.

The grief and anguish of the day live with me yet. The French have the most apt word for it – tristesse.

The expert help I have had to deal with my tortured, irrational thoughts has been excellent.

I realised I had avoided even driving past the school ever since the shooting.

Compared with others, I regard my connection to this tragedy as quite small.

Yesterday, I laid flowers and a card at the altar the school placed in memory of Nanette Hanson.

Her legacy of courage and selflessness stands as an inspiration to us all.

My visit, though tinged with sadness even after all these years, was nonetheless inspirational.

I am greatly touched that today’s generation of staff and pupils keep alive the memory of a very brave teacher.