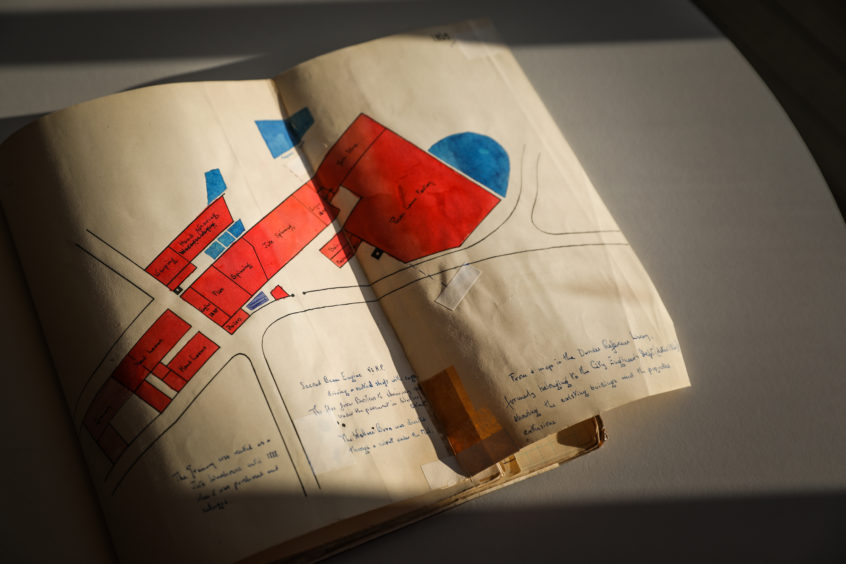

The distinctive yellow lettering of “William Halley & Sons Ltd” could be seen reflected on the waters of the River Tay all the way from Fife.

The jute mill stood tall, near the river, and employed countless people over generations in Tayside and Fife.

Craigie Wallace Estate, known as Halley’s Mill, was a landmark in the city for more than a century and a major part of Dundee’s booming jute industry.

But after the factory’s closure in 2002, the building fell into a state of disrepair. It was unceremoniously torn down in 2018 and a police investigation into the legality of that action is ongoing.

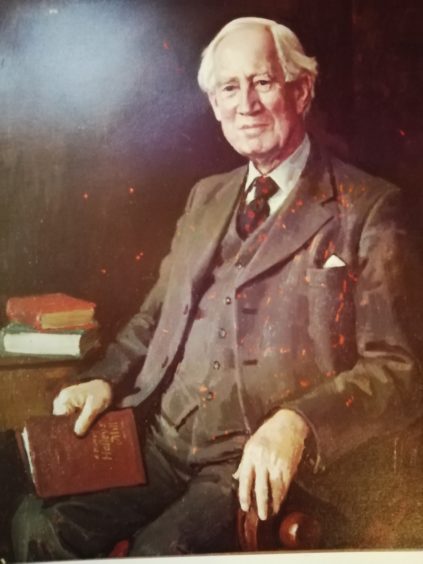

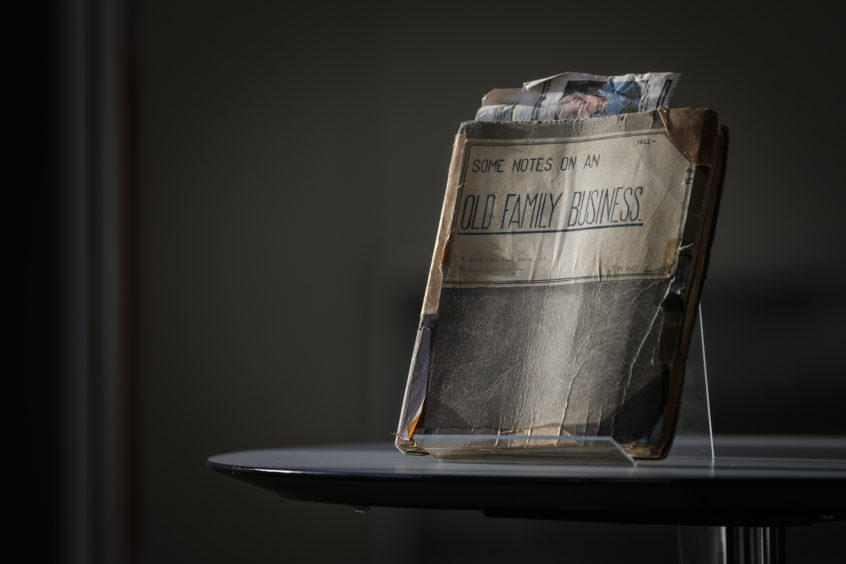

Guy Halley has shared a personal family book that documents the history of the site and illuminates its importance to the area.

Some Notes on an Old Family Business is in good condition, considering it was started in 1953 by Guy’s grandfather, Roy Halley.

It not only offers a unique inside view into the workings of a historic mill but also of the wider textiles industry through the years.

Roy scoured records and documents to piece together a detailed history of the times jute became prominent.

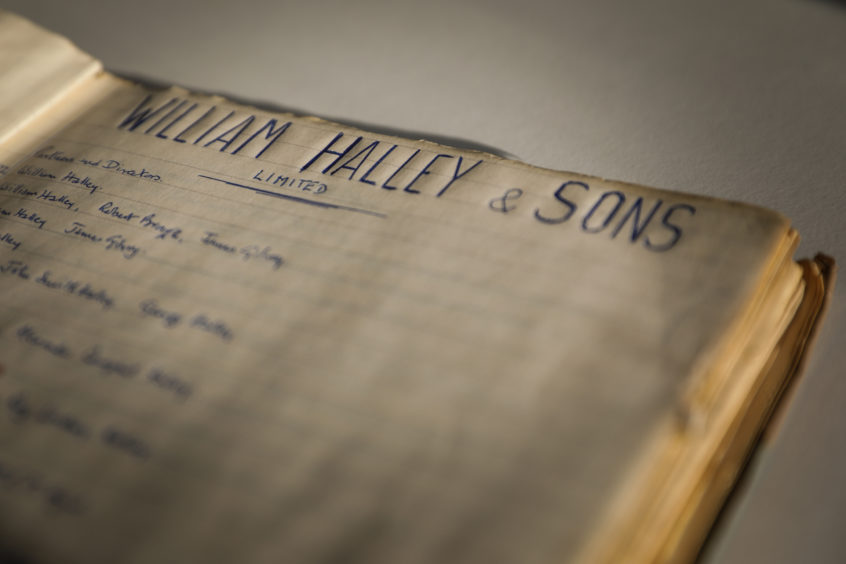

The book opens with a listing from some of the key figures from the early history of the mill, along with a list of their nicknames such as Cracked Ironhead, Judas and Not Competent.

It also includes short biographies, such as that of David Blair, the son of a Brechin minister born in 1750. He earned the nickname “Faulty” for his habit of “frequently ejaculating that word when inspecting cloth which he deemed scarcely up to the mark”.

One section tells the tale of John Halley, who came to Dundee from Perth in 1782. In writing about John, Roy questions if the Halley name originates from the Belgium town of Halle.

Also included in the tome is an essay on the early days of power-driven flax spinning. It explains the first flax spinning mill driven by power was erected in Inverbervie in 1787.

In 1822, the number of people working in the linen trade in Dundee was about 3,000 and by 1831, 6,828 people were employed, 600 under the age of 14.

It was in this buoyant environment that Halley’s mill was built.

The building itself was erected with brick and cast iron and was the first “fire proof” mill in the city. For its first 70 years, only the roof was insured.

The slower communication methods of 1835 — messages took three weeks to cross the Atlantic — led to an overproduction of hemp across Dundee and too much cloth being sent to New York.

This resulted in materials sitting in storage for months, unused and unsold. There was a drop in the price of hemp but an increased interest in jute.

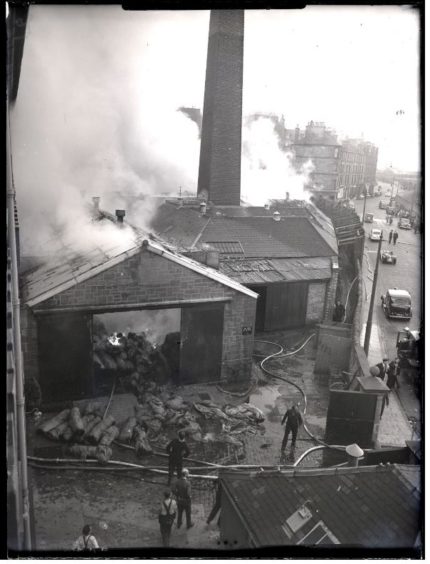

A blaze in a Dock Street mill the same year destroyed 300 tonnes of uninsured jute.

Details are vague in the boo, but it notes the owner of that mill became one of the leading figures in establishing Dundee Fire Brigade.

Discipline in the mills was strict in 1861.

Roy wrote about an advert in this paper in 1836 which warned flax spinners not to “engage a defaulting apprentice”, giving the offending man’s name and description.

The man, who Roy did not name, is said to have “grossly neglected his work for the avowed purpose of procuring his discharge” — he wanted to get sacked.

In 1837, a downturn in the fortune of many businesses across Scotland helped secure jute as a popular, cheap raw material.

The next year, the Dutch government agreed to buy jute for the production of coffee bags, securing its popularity.

Conflicts such as the American Civil War and the Second Boar War were said to have been good for business demand for jute soared further.

While the jute and wider textile industry always had its peaks and troughs, a particularly bad two-year spell began in 1903 with profits falling and the period between the world wars was also turbulent.

In 1958, industry activity fell by 15% as demand lessened and further diversification was touted as a way to save the ailing Tayside industry.

A major blow in 1963 came in the form of the Restrictive Trade Practices Court, declaring the jute industry’s price agreement as being against the public interest.

A year later, bad flooding caused prices to “rocket suddenly”.

Despite at least a decade of industry-wide set backs, the Halley family decided to set up a mill in Perth in 1969 to spin yarn for the carpet industry.

The venture cost £500,000 (£6.9m today).

Conditions in the jute industry continued to falter and by 1971, it was estimated 3,000 British jobs had been lost.

That year saw W G Grant & Co Ltd sites in Dundee and Carnoustie close, as well as T L Miller & Co Ltd in Dundee and Douglas Fraser Sons Ltd in Arbroath.

International politics was having also an effect.

The book states: “Political trouble in East Pakistan was suppressed by the Pakistan army, and an estimated 10 million people fled over the border to West Bengal in India.

“Since this occurred at the time of the jute crop should have been sown, it caused considerable uncertainty in the Dundee industry.”

Again, going against the grain, the Halley family decided to modernise in 1974 with the purchase of 12 new “Gripmack” looms.

These would weave either jute or polypropylene, which is similar to plastic.

But that same year, the axe came down on 105 jobs in the factory.

And in 1980, further heartbreak was wrought upon workers in the area as several factories closed.

These included Tay Textiles Dura Works and Hardie and Smith.

Halley’s Mill stripped back its polypropylene operation in 1982, which resulted in the loss of 200 jobs.

A chart detailing industry-wide jute production post World War II shows a sharp decline in the late 1960s, which continue to fall at an alarming rate through the 70s.

The factory finally closed in 2002, but the book goes into little detail beyond the decline of the 1980s as Roy aged. He died in 1998.

The book contains a fairly detailed account of the lives of other relatives and drawings of the family tree.

Guy Halley — who now lives in Yate, England — is proud of his family’s role in Dundee history.

He said: “My grandfather would have been really pleased to share this information with Dundonians.

“He always spoke warmly of Dundee. He loved Scotland so much he never wished to travel outside of the country.

“He had a great interest in the city and would like the people to see what the book offers.

“The book has an interesting insight into Dundee and the conversation between times of war and business doing well, for example.”