Ninety years after the General Strike almost brought Britain to a standstill, Michael Alexander looks at its impact on Fife and Dundee.

It was a watershed moment for labour relations that bitterly divided opinion and still resonates in many former mining communities to this day.

Just seven years after the end of the slaughter of the First World War trenches, millions of workers across the country downed tools to take part in the biggest walkout in British history, taking a stand against savage austerity cuts imposed by a Liberal-Conservative government.

Britain’s first and only General Strike began at midnight on May 4 1926, and ended nine days later.

It was called by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in support of one million coal miners – including thousands in Fife – who had been locked out of their mines after a dispute with the owners who wanted them to work longer hours for less money.

It was the latest in a long series of industrial disputes that had dogged the coal industry since the end of the First World War and created real hardship for mining families.

Across the UK, vast numbers of workers from other industries downed tools in solidarity including bus, rail and dock workers, as well as people with printing, gas, electricity, building, iron, steel and chemical jobs.

The industrial action, which resulted in fights between police and strikers in some communities, came against a backdrop of tough economic times following the First World War and the establishment’s growing fear of communism.

Yet nine days after it began, the TUC, which had been holding secret talks with the mine owners, called off the strike without a single concession made to the miners’ case.

The miners battled on alone. But by the November they too drifted back to work. The following year the government passed the 1927 Trades Disputes Act, which banned sympathy strikes and mass picketing. It was repealed in 1946 but the ban on secondary strike action was reintroduced by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1980, and continues to this day.

Independent Fife councillor Willie Clarke, the only self-described communist holding elected office anywhere in the UK, started representing the former mining town of Ballingry 43 years ago this week.

And the former miner, now aged 80, revealed that when he started working down the Glencraig pit at the age of 14, the General Strike “lived on” in the memory of Fife’s mining communities and still does.

“My uncle, also called Willie, was involved in the 1926 General Strike, “recalled Willie, who joined the Communist Party as a teenager at a time when it was integral to life in the Cowdenbeath area.

“I remember my mother telling me about the battles between the police and miners. Around 12 of the miners were jailed at Dunfermline Sheriff Court for between 10 months and a year. What happened then was that the Communist Party, which was huge in the mining communities at that time, struck a medal for each of them.

“When they got released from Saughton Prison and then got the train back over to Fife, the pipe band went up to meet them off the train at Lochgelly station. It then played them through the town and the Communist Party presented them with medals at the Institute. The whole community turned out. These were working class heroes!”

Willie, who was elected to the council just days before the deaths of five miners in the Seafield Colliery Disaster of May 10, 1973, said that many of the veterans from 1926 were still around during the miners’ strikes of 1972, 1974 and 1984, and there was still a strong sense of pride in their forefathers. However, there also remained considerable bitterness. And some who had broken the strikes had still been ostracised by their communities.

He said the role of women in supporting the miners during the 1926 strike was often forgotten. And it was a point he was keen to stress when he offered support and advice to the makers of the 2013-released film The Happy Lands, an acclaimed big-screen account of the General Strike which investigated the human side of how the Fife mining villages and the working-class heroes who fought for better conditions were made to suffer.

However, not everyone supported the 1926 strike. In many areas middle-class volunteers got some buses and trains and the electricity working.

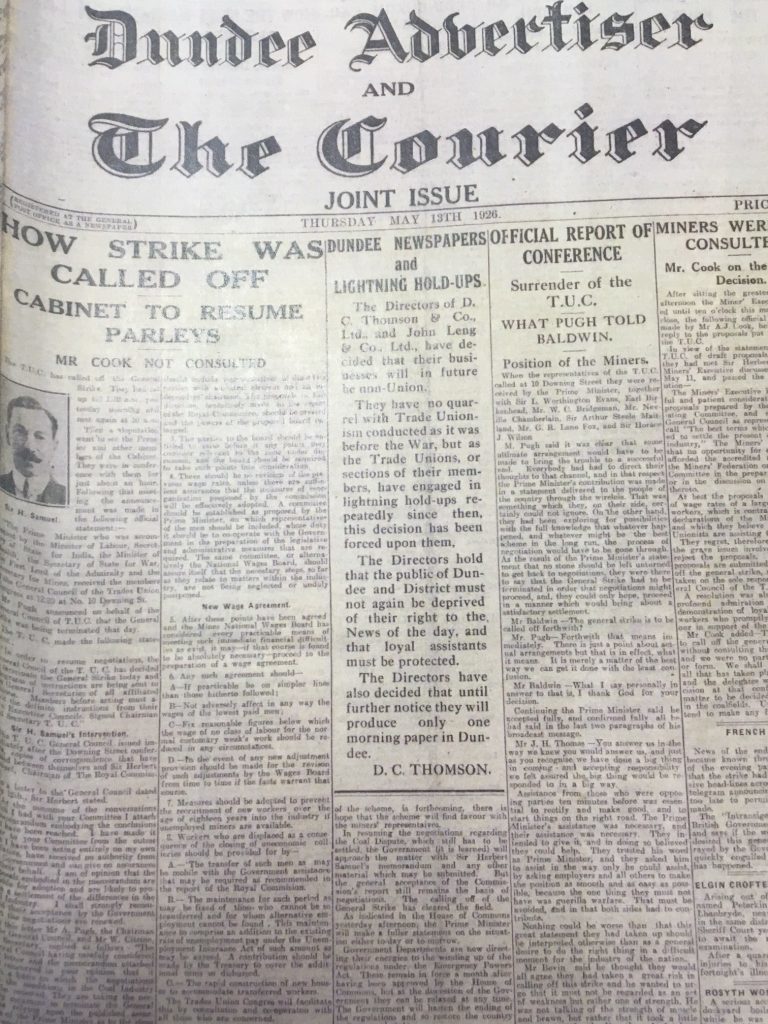

A joint issue of The Dundee Advertiser and The Courier on May 11 1926 reported the strike’s “complete failure”. With Dundee print workers involved in the strike, it also led to the directors of Courier publishers DC Thomson & Co Ltd making their businesses at that time “non-union”. They also decided to merge The Courier with The Advertiser, creating the single newspaper that still exists today.

Dr Billy Kenefick, senior lecturer in history at Dundee University said that for workers in Fife who were miners, the General Strike was a “nightmare and a complete disaster for the mining communities as a whole.”

He added: “I do not know the Scottish figures but across the UK as a whole there were a third less miners by the late 1930’s than before the General Strike was declared when there were around 1.2 million.

“As for Dundee workers, many returned to work on the May 13 with few if any problems.

“But that was not the case for the print workers and the printing trades.

“Outram Press in Glasgow and DC Thomson in Dundee would only employ non-union labour after the strike which led to a boycott called by the Scottish TUC Strike Committee ‘not to purchase’ any of the title produces by either publisher (The Glasgow Herald, Evening Times, The Bulletin, Glasgow Weekly Herald and the Glasgow Evening Citizen: for Dundee the Weekly News, People’s Friend, People’s Journal, Topical Times and the Sunday Post).

“Those who were not re-employed formed the backbone of the Dundee Free Press which managed through to 1933 before finally shutting down.”

Ian Waddell, 63, is chairman of Fife Trades Union Council. His grandfather William Munro was involved as a striking miner in the 1926 strike in the Buckhaven/Methil area and was blacklisted by the Fife Coal Company as a result. William remained bitter for the rest of his life.

But Ian said that despite the passage of time, lessons from the General Strike remained relevant in 2016.

He said: “One of the things the STUC is trying to combat at the moment is Zero Hours contracts. They are the modern manifestation of what was happening in 1926. I think the role of getting people unionised is important, and the STUC is doing well getting younger people involved – young people who are furious about the way Zero Hours contracts operate.

“But it’s interesting that the ban on secondary strike action still stands. If not then I’m pretty sure we could have had nurses walking out in support of the striking junior doctors in England by now.”